On British Cinema

The fascinating thing about today’s cinema is that, as an art form, it is so varied. Mike Leigh’s films, for instance, which, with regard to cinematic skills are stripped down to the essentials — two people talking in a room and then climbing onto a motorbike to go and talk with two more people in another room — without even allowing us to see the imagined bike ride —are just as valid as films like Harry Potter that call for every trick and tool in the cinematic toolbox and take us on magical motorbike rides we could never imagine.

Before the advent of the UK Film Council there were interminable seminars about the depressed state of the British industry and the future of film — and then more seminars about seminars. Most of us got bored with it and got on with making films – mostly in the US where they think a seminar is something Russians drink tea out of.

Too many untalented people were given money by the old Arts Council. It isn’t a God given right for everyone to make a film and the people shouting for years to get their films made were found out to be mostly hopeless. Almost all of them drowned in the big pond of government subsidy, never to make another film. But it was a great reality check—a cleansing process really—because it got rid of a horde of yappy dilettantes.

Ever since film began in the UK — at any given time —you can count the number of outstanding directors on two hands. It’s never changed. Good writers have been more plentiful —maybe two hands and a foot.

Francois Truffaut said that British Cinema was an oxymoron. (Like French Rock music.)

I admire Mike Leigh and Ken Loach so much. They’re like Mick Jagger and Keith Richards: they do a gig every couple of years, doing ‘Jumping Jack Flash”— the same old stuff you’ve heard a million times before— and we all lap it up.

For a long time the British Film Industry was just a bunch of people in London who couldn’t get Green Cards (allowing them to work in America).

Bumping into David Lean at Pinewood Studios, he asked me where I had made my last film. “America, Sir” I stuttered. “America?” he repeated — pronouncing the word like something on the bottom of his shoe.

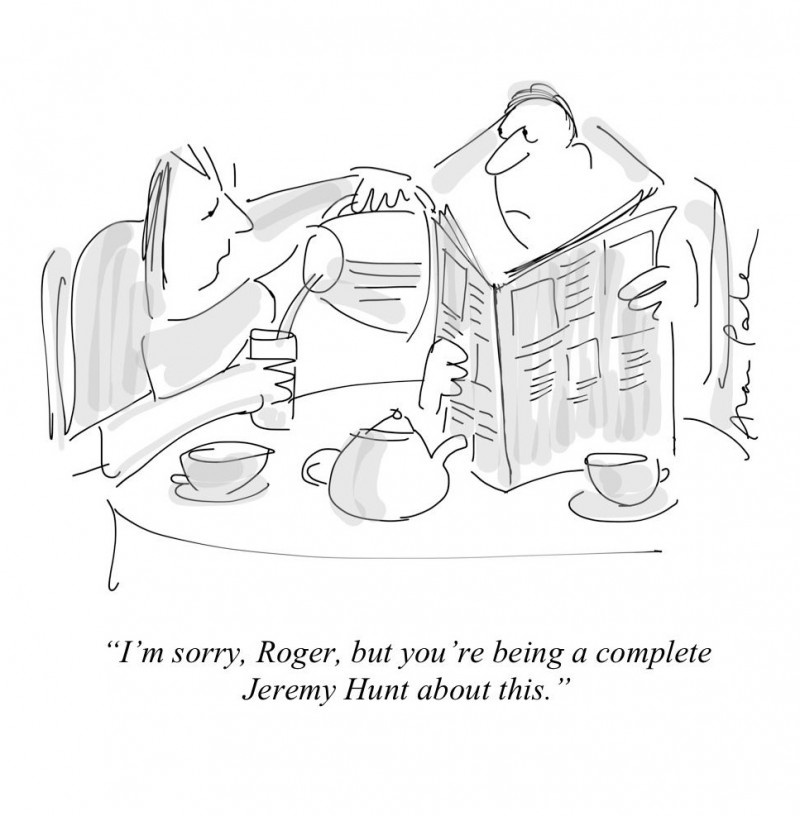

Abolishing the UK Film Council was a hasty, petulant act of political vandalism executed by an arrogant and ignorant right wing ideologue, Jeremy Hunt, following the 2010 election.

“Look how they massacred my boy.” Don Vito, The Godfather.

Merging a commercial organization like the Film Council into a cultural one like the BFI is a mistake resulting in a disservice to both culture and commerce. It’s like asking Nicolas Serota to be a judge on X Factor.

The Film Council couldn’t be Clark Kent scooting into a phone box and turning the film industry into Superman.

At the centre of the British Film Industry is a black hole that you don’t need Stephen Hawking to explain. In the sixties and seventies, the large, established British film and entertainment companies appeared to experience the business equivalent of a frontal lobotomy, thereby committing hara-kiri.

There are those who provide content and those who deliver it, and whenever they’re disconnected, you get the fragile, cardboard city we presently inhabit.

The British Film Industry is such a quaint phrase, considering the bewildering speed with which our vocabularies and our lives are being downloaded.

Sometimes, with the British Film Industry it’s hard to know if we’re waving or drowning.