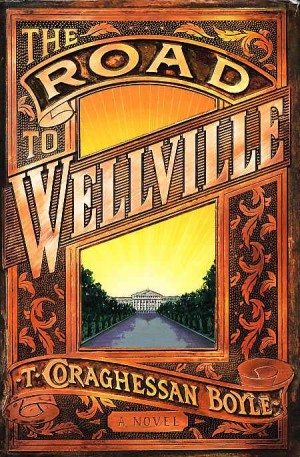

THE ROAD TO WELLVILLE

The making of the film by Alan Parker

I was first sent the manuscript of T.Coraghessan Boyle’s novel, “The Road To Wellville”, in July of 1992. I was immediately drawn to the three interwoven stories and the outrageous, eccentric world that Tom Boyle had parachuted us into with all of his usual anarchic and irreverent wickedness. And so by August, with the rights secured, I began the first steps on the road that led to The Road to Wellville

was first sent the manuscript of T.Coraghessan Boyle’s novel, “The Road To Wellville”, in July of 1992. I was immediately drawn to the three interwoven stories and the outrageous, eccentric world that Tom Boyle had parachuted us into with all of his usual anarchic and irreverent wickedness. And so by August, with the rights secured, I began the first steps on the road that led to The Road to Wellville

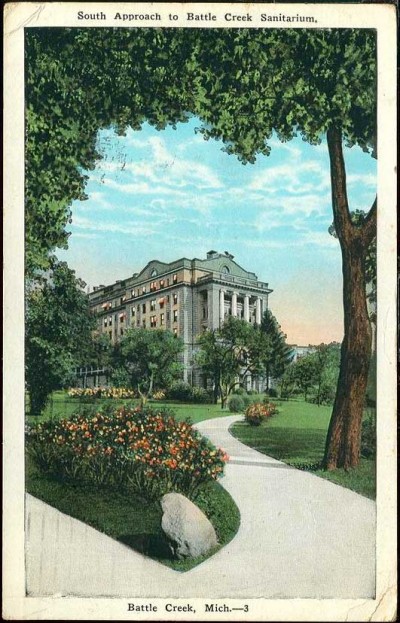

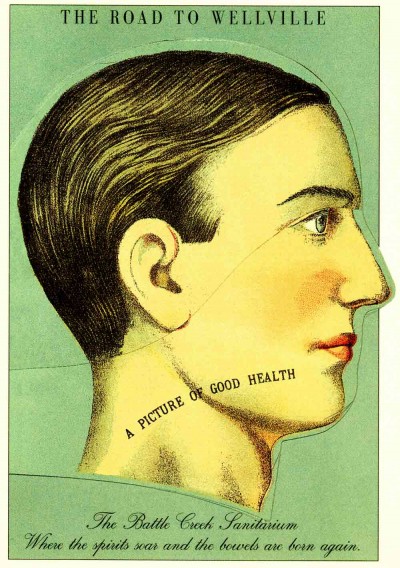

Before starting work on the screenplay, my first task was to immerse myself in the research behind the book and to dig deeper for the references needed to recreate the unique world of Dr. Kellogg’s Battle Creek Sanitarium. Visits to Battle Creek, in the southeast corner of Michigan, yielded a mountain of faded photographs and memorabilia. The Doctor’s penchant for documenting everything he did and his nose for publicity (he was one of the first to master the “photo op”) gave us over two thousand photographs and technical drawings to work from.

Some Historical Background

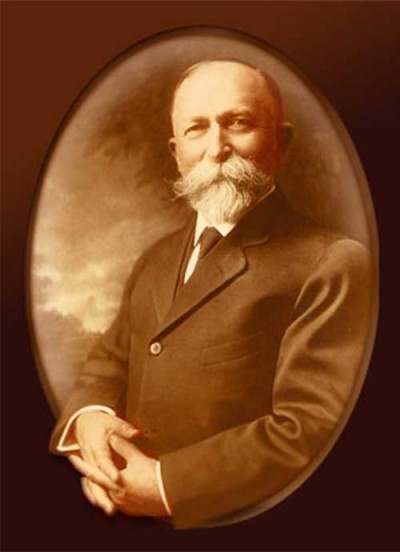

The Battle Creek Sanitarium began life as the Western Health Reform Institute, founded by the religious group, the Seventh Day Adventists, in 1866. The creed of vegetarianism had been adopted by the Adventists at the urging of Sister Ellen White, one of its leaders, who, apart from claiming the notion in a vision from God, had found enough Biblical references to justify the precept. The Western Health Reform Institute stumbled along with minimal success. What was needed, it was decided, was medical credibility to match the religious fervor. And so a young Adventist, John Harvey Kellogg, was dispatched with a $1,000.00 loan from Ellen White to Bellevue Medical College in New York to gain a medical degree. As fortune would have it, they chose the right man. John Harvey returned to Battle Creek to take over the Institute in 1876 and hastily began to reform it along legitimate medical lines.

John Harvey Kellogg, Battle Creek Sanatarium

With formidable energy he expanded the original, rather tame, regimens of acorn coffee, ice cold hip baths and Indian club exercises to almost unthinkable dimensions as he adopted new ideas from around the world, coupled with his own extraordinary fertile imagination. By the turn of the century, the renamed Battle Creek Sanitarium (the Doctor coined the word ‘Sanitarium’ because ‘Sanitorium’ had connotations of establishments specializing in the cure of tuberculosis) rivaled the great European spas of Karlsbad, Vichy and Baden-Baden as the grand San lobby, “busy as a bus station”, buzzed with the rich and famous of American society. The ideal guests were “overweight women and overworked men” who rubbed shoulders with fellow patrons Henry Ford, Teddy Roosevelt and John D. Rockefeller. They would close their houses for the season to “boil out” and take “the cure”. Such was the celebrity of “The San”, as it became known, the cable address was simply, ‘HEALTH’.

Over a thousand guests, looked after by as many staff, dedicated themselves to the good Doctor’s philosophies of “the meatless life” and “biological living” in their search for a cure of their “peristaltic woes”. Their daily diets could include granola, stewed raisins, cereal coffee, cabbage salad, okra soup, shredded carrot, escalloped vegetable oysters, baked onions, Protose patties (beefsteak substitute), stewed figs, Kaffir tea, hot malted nuts, bean tapioca, nut lisbon steaks, corn pulp, gluten mush and squash pie. Not that their stomachs would be full for long thanks to the Doctor’s obsession with cleaning out the bowels with enemas: “I assaulted the bowel with sterilized bran and paraffin oil from above, and hosed it out with torrents of water from below”. He was particularly fond of Bulgarian yogurt, an idea he had borrowed from Eli Metchnicoff at the Pasteur Institute, which Kellogg took further by administering it to his patients at both ends of their anatomy. (One assumes that the resulting collision annihilated the dreaded toxins).

Matthew Broderick on the treadmill

The dynamic, diminutive Kellogg (he was 5’4″ —”I have rather short legs, otherwise I’d be a much taller man” —was at the center of everything. He invented 75 different kinds of foods, including cornflakes and peanut butter. His inventions were tried out on the ever-receptive patients/guests, eager to try his new vibrating belts, chairs and beds, his ultraviolet and infra-red electric light baths, electric blankets, the sinusoidal current baths as well as a choice of 200 other kinds of baths, douches, scrubs and hydriatic percussion. They could bicycle across the four hundred acres of farmland, which yielded the San’s vegetables, fruit and dairy products, or visit the scores of greenhouses and view two thousand heads of Chinese cabbage. At the end of the day, they could relax in the luxurious Palm Court to the strains of the San String Orchestra (punctuated, apparently, by frequent dashes to the bathroom) or dance ‘The San Waltz’ (everyone ‘danced’ without touching, because the Doctor thought that dancing in the normal sense was dangerous because it “aroused hidden pleasures in a woman”). Kellogg was also performing daily surgical operations, removing large chunks of people’s intestines with apparent abandon, but sewing them up very skillfully. (A Kellogg scar was much admired for its neatness: a skill he put down to being taught needlepoint as a child by his mother). A consummate showman and self-publicist, he always dressed from head to foot in white “to more beneficially receive the sun’s rays” (and, no doubt, to stand out in photographs), he dictated continuously to his secretaries during his manic daily schedule as he tirelessly traversed his San fiefdom. He even dictated in his bath and, apparently, during his enemas (as he had as many as five a day, this was obviously a convenient use of his valuable time). He wrote over fifty books which castigated everything from the meat glutton to fashionable dress and sexual misconduct. Almost every ill in society, from violent crime to poverty, he attributed to unhealthful foods and sexual behavior.

The dynamic, diminutive Kellogg (he was 5’4″ —”I have rather short legs, otherwise I’d be a much taller man” —was at the center of everything. He invented 75 different kinds of foods, including cornflakes and peanut butter. His inventions were tried out on the ever-receptive patients/guests, eager to try his new vibrating belts, chairs and beds, his ultraviolet and infra-red electric light baths, electric blankets, the sinusoidal current baths as well as a choice of 200 other kinds of baths, douches, scrubs and hydriatic percussion. They could bicycle across the four hundred acres of farmland, which yielded the San’s vegetables, fruit and dairy products, or visit the scores of greenhouses and view two thousand heads of Chinese cabbage. At the end of the day, they could relax in the luxurious Palm Court to the strains of the San String Orchestra (punctuated, apparently, by frequent dashes to the bathroom) or dance ‘The San Waltz’ (everyone ‘danced’ without touching, because the Doctor thought that dancing in the normal sense was dangerous because it “aroused hidden pleasures in a woman”). Kellogg was also performing daily surgical operations, removing large chunks of people’s intestines with apparent abandon, but sewing them up very skillfully. (A Kellogg scar was much admired for its neatness: a skill he put down to being taught needlepoint as a child by his mother). A consummate showman and self-publicist, he always dressed from head to foot in white “to more beneficially receive the sun’s rays” (and, no doubt, to stand out in photographs), he dictated continuously to his secretaries during his manic daily schedule as he tirelessly traversed his San fiefdom. He even dictated in his bath and, apparently, during his enemas (as he had as many as five a day, this was obviously a convenient use of his valuable time). He wrote over fifty books which castigated everything from the meat glutton to fashionable dress and sexual misconduct. Almost every ill in society, from violent crime to poverty, he attributed to unhealthful foods and sexual behavior.

Sex was such an issue with Kellogg that he proudly set the example of a celibate life (with his schedule, it seems he would hardly have time for such things, anyway).

DR. KELLOGG

Connubial relations, Sir. Your natural urges.

Sex. Candidly, Mr. Lightbody, this lump of flesh

that dangles between your legs is a dangerous weapon.

It will have to be harnessed. Locked away. Retired.

I warn you Sir. An erection is a flagpole on your grave.

His wife, Ella Eaton Kellogg, “a spry wisp of a woman”, besides looking after their adopted children (there were eventually forty-two of them), experimented extensively for nearly twenty years with imaginative new recipes and methods of food preparation in her endeavor to make the San’s menu more palatable. The Doctor’s original veal substitute, ‘Nuttose’, was described as “like eating a slab of shoe-maker’s wax” and getting through a plateful of his more fibrous products was described as “trying to swallow a whisk broom”. This drove the Doctor onwards to new inventions: “I once proscribed Zweiback to an old lady, and she broke her false teeth on it. I began to think that we ought to have a ready-cooked food that didn’t break people’s teeth. I puzzled over that a great deal”.

He lectured daily with colorful and threatening language: “The meat eater is drowning in a tide of gore”. He drew on history, attributing genius to vegetarianism, from Pythagoras to Isaac Newton. (One assumes Newton ate the apple after it hit him on the head, which was good enough for the Doctor). He even went as far as to claim that “Rome’s collapse was well underway when slaves were thrown into the eel pots to increase the gamey flavor of the eels when they came to table”. The guests lapped it up as they sat there bolt-upright in their orthopaedically-correct chairs with “30 feet of fear coiled up inside of them”.

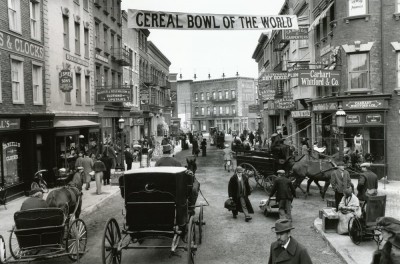

Outside the sanctity of the San’s gates the effects of the Doctor’s food inventions were causing all sorts of mayhem in the small town of Battle Creek, as breakfast food companies sprung up everywhere. Someone remarked that Battle Creek had 21,647 inhabitants, and all of them seemingly engaged in the breakfast food business. One by one, new products emerged as the breakfast food gold rush echoed the entrepreneurial optimism of a young country entering a new century. Hello-Bito, Malt-Ho, Try-a-Bita, Oatsina, Foodle, Krinkle, Fush, among dozens of others, were thrust upon a hungry public. Whole families put their life savings into these endeavors, sometimes based on merely a catchy name, produced in ramshackle factories with dubious recipes.

Outside the sanctity of the San’s gates the effects of the Doctor’s food inventions were causing all sorts of mayhem in the small town of Battle Creek, as breakfast food companies sprung up everywhere. Someone remarked that Battle Creek had 21,647 inhabitants, and all of them seemingly engaged in the breakfast food business. One by one, new products emerged as the breakfast food gold rush echoed the entrepreneurial optimism of a young country entering a new century. Hello-Bito, Malt-Ho, Try-a-Bita, Oatsina, Foodle, Krinkle, Fush, among dozens of others, were thrust upon a hungry public. Whole families put their life savings into these endeavors, sometimes based on merely a catchy name, produced in ramshackle factories with dubious recipes.

At Battle Creek railway station, travelers would be accosted by brokers offering shares in future (or non-existent) breakfast food companies. The Doctor, urged on by his younger brother Will, seeing the invention exploited so successfully by others, (the flaking process could turn a 60-cent bushel of wheat into breakfast food retailing for $12.00), finally went into the marketplace himself. Will K. Kellogg, eight years his brother’s junior, and forever in his gregarious older brother’s shadow, had quietly helped to run the administration of the San for many years. As he was paid a rather stingy six dollars a week, and once went seven years without a vacation, it’s hardly surprising he finally left his brother and set up on his own in 1911, eventually making his fortune, much to his brother’s displeasure (the two brothers rarely spoke from then on). Ironically, Will’s own name, W.K. Kellogg (his signature on every box), was to become the one the world would ultimately associate with the cornflake.

And so to the film—

So successful was the San that the pious Seventh Day Adventist, who had spawned, it grew somewhat alarmed at the dramatic transformation of their establishment, which had become resoundingly “Kelloggian” and barely Adventist. “Foodism” had become its own religion. Sister Ellen White pronounced that “The Lord is not very pleased with Battle Creek” and had another one of her visions, foreseeing a “sword of fire” over the San. Sister Ellen was rarely wrong about such things it seems, and the giant wooden structure that had so hurriedly mushroomed in all directions over the years mysteriously burned completely to the ground in February of 1902. Undaunted, the Doctor rebuilt an even bigger San, within the year, on the same spot. This building still survives in Battle Creek, but the palm court, bath houses and acidopholous milk bars are no more, having been converted into a very ugly Federal Building.

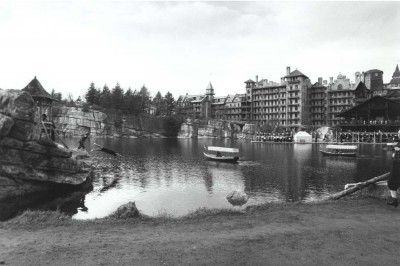

Consequently, after finishing my screenplay, our first task was to search out a location, a building that matched the Kellogg original. To that end, we checked out every giant period building in fifty different states. From mental health institutions in Kinkakee, Illinois and Yankton, South Dakota to hotel spas in French Lick, Indiana and Hot Springs, Arkansas. From vacant prisons in Montana to Catholic seminaries in Baltimore. We eventually decided on the Mohonk Mountain House perched high in the mountains of the Shawangunk Ridge at New Paltz, ninety miles north of New York City.

Arrival at he Battle Creek Sanatarium (AKA The Mohonk Mountain House)

The enormous hotel had survived with much of its period detail intact, still owned and operated by descendants of the two Smiley Brothers who had started it over one hundred years previously. The Smileys were strict Quakers and consequently the hotel had not rushed headlong into comtemporizing its facilities, relying on the extraordinary beauty of the setting on Lake Mohonk and the surrounding countryside to attract visitors. It also had a close resemblance to the wooden structure of the original ‘San’ as its unique, eccentric architectural development seemed to parallel the San’s — with 238 verandas, turrets and balconies popping up all over as it grew over the decades — following necessity, rather than a greater architectural design.

Production Designer Brian Morris and I had decided that almost all of the interiors of the San would have to be built, as nothing resembling Kellogg’s eccentric world existed (in North America at least). Our film is set in 1907, and we also had to recreate the town of Battle Creek, which now has little or no resemblance to the period of our film. And so we began work on building the interior sets and exterior streets at the studios in Wilmington, North Carolina.

We had decided on Wilmington because North Carolina is a designated ‘right to work state’—basically, one of the 22 American states, mostly in the South and Mid West, who allow fee flow of labor without the membership or non-membership of a local union. This was of pragmatic importance to us as my crew, who have worked on most of my movies, are an amalgam of British, New York and Los Angeles technicians. Dino De Lauretiis had originally built the studios in Wilmington deliberately to take advantage of North Carolina’s open arms labor policy. The studios, although no match for their Hollywood and British counterparts, were a comfortable place to work albeit snuggled as they are in between the State Penitentiary and the local sewage plant. They are also a stone’s throw from the local airport. (However when the planes are flying overhead during a sound take, the only stones thrown are upwards, by the sound department.

I also had to set about the mammoth job of casting. My screenplay called for 56 speaking parts, and I began casting in New York, Los Angeles, Upstate New York and also in North Carolina.

Anthony Hopkins was my first choice for Dr. Kellogg, and it was some months before he agreed. As he tells it, we had dinner in Los Angeles in May of 1993 and to stop me pathetically begging him to do the part any more, he immediately said yes so that we could enjoy the rest of our dinner. Great mimic that he is, I feel that possibly his impersonation of me, on my knees and in tears, is closer to the National Theatre than the reality of the Italian restaurant we were eating in at the time.

I think he rather enjoyed the challenge of playing a more extrovert role, which is somewhat different to what audiences have come to expect of him in recent films. His Kellogg is flamboyant and outrageous, and it also allowed him to play a quintessentially American character. John Harvey Kellogg’s language had been described as “King James Bible English with a little Mark Twain thrown in”, I sent Tony some archive early recordings of Teddy Roosevelt who had a clipped, almost English twang and Tony adapted this to his own particular Kelloggian solution: to portray the showman of health, as he strode the shores of the alimentary canal, expounding his beliefs with the resolve of an evangelist and the guile of a snake oil salesman.

DR.KELLOGG

The meat eater is drowning in a tide of gore. What is a sausage? An indigestible balloon of decayed beef riddled with tuberculosis. Eat it and die. …masturbation is the silent killer of the night: the vilest sin of self pollution.

Tony had met with our Costume Designer, Penny Rose, in London to finalize his white-suited, linen costumes and on arrival in New York, head shaven and goatee beard in place, he presented me with his final notion: a set of enlarged front teeth which he’d had made for him in London. His idea had variously come from Teddy Roosevelt’s “mouthful of teeth” or (as he would have it) in a vision worthy of Sister Ellen White, from watching TV, half asleep, and seeing a cartoon featuring that other famous vegetarian, Bugs Bunny.

Anthony Hopkins (John Harvey Kellogg) squeezes Mrs Portois’s cheek

By the end of the summer I had finalized the rest of my main cast who were willing to join me on this scatological adventure and be part of a large ensemble —not always attractive to the Hollywood actors. Bridget Fonda agreed to play the part of Eleanor Lightbody, a “Battle Freak” who arrives at the San with a shaky marriage and who, with a little resolve and excessive distraction, finds her way to fulfillment, representing as she does, the women of her time who were bravely tip-toeing into a hopeful, emancipated new century.

VIRGINIA

He’s Lionel Badger of the American Vegetarian Society. He wrote a wonderful paper on the clitoris.

ELEANOR

I thought you said he was a vegetarian?

VIRGINIA

Oh, it’s all related darling.

Matthew Broderick was to play Will, our guide through the San madness, who is douched, scrubbed, fried, poked, prodded and purged, his intestines “snipped out like a wart” as he fights a resentful stomach and pursues his errant wife.

DR. KELLOGG

Nurse, take Mr. Lightbody to the Yoghurt Room immediately. Give him fifteen gallons.

WILL

But I can’t possibly eat 15 gallons of yoghurt.

DR. KELLOGG

Oh, it’s not going in that end Mr. Lightbody.

John Cusack was to play Charles Ossining in the third of our stories, as the young entrepreneurial, gullible hustler who forever juggles unbridled ambition with dishonesty, treading the tightrope between capitalistic enterprise and a less noble greed — cajoled by the mendacious Goodloe Bender (Michael Lerner).

BENDER

As day follows night, Charles, one truth is undeniable: behind every shining fortune lurks the shadow of a lie. That’s what business is…

HEALTH! The open sesame to the sucker’s purse.

Saturday Night Live’s Dana Carvey completed the five main cast members as George Kellogg, John Harvey’s spurned, renegade son — complete with yellowed, broken teeth, butchered, greasy hair, protruding ears and face sores. (Or, as Dana put it: “It’s the only film I ever did where the make-up department are pleased if I stay up all night”.)

BENDER

Charles, this worthless bundle of piss and vomit beneath our table is the good Doctor’s estranged adopted son.

It’s always a mistake to zip through the main casting of a film. Frankly, it’s all the financiers or studios care about. In the case of Wellville it was a hefty cast to assemble before we were given the green light on the film. It has to be said, of course, that films can live or die because of the main cast. Certainly, if you get the casting wrong, then chances are you’re going to get the film wrong. The same can be said for the quality of the casting, down to the smallest role, that surrounds the principal actors. Wellville is an ensemble cast, and arguably, that ensemble is twenty actors deep. In supporting roles I was fortunate enough to have Camryn Manheim (Virginia) It was odd to see Camryn daintily peddling her bicycle along the forest path, when I cast her she had arrived in full leathers on a 1000cc motorcycle.

VIRGINIA

My dear, I have very little use for my husband in the sexual gratification department…and so I find a long ride on my bicycle, in my bloomers, once a week, does the trick. “Bicycle Smile” I believe they call it. It’s changed my life.

And Lara Flynn Boyle as Ida Muntz, Will’s ill fated neighbour and sexual distraction. Both Lara and Camryn both went onto went on to success in TV’s ‘The Practise.

MISS MUNTZ

To Casanova’s overcoat…to…to Charles Goodyear, who made possible the vulcanized rubber condom.

MISS TINDERMARSH

What does she mean?

We had cast the indomitable British actor John Neville as Enymion Hart Jones:

HART-JONES

Yes, I too was like you Will. But after a few weeks of relentless roughage, I dumped a whopper in my toilet as big as Long Island.

And Roy Brocksmith who plays Kellogg’s faithful aid-de-camp: Poultney Dab.

DAB

I think George must have gained access to the latrines.

KELLOGG

Latrines?

DAB

Sir, he’s throwing boxes of shit at the guests.

Also I should mention two actors that I’ve worked with before. Curiously enough I rarely work with actors more than once, but I’ve made three films with Colm Meaney (The Commitments, Come See the Paradise and Wellville where he plays Dr. Lionel Badger. Also we had Norbert Weisser (who I had previously worked with on Midnight Express) as Dr. Spitzvogel the expert at “handhabunging.”

…she sank beneath it, dreaming of those sylvan glades, of men and women gamboling through Bavarian meadows, as naked as God made them, and she felt herself moving, too, the gentlest friction of her hips against the rubber padding…

Camryn Manheim (Virginia Cranehill) and Bridget Fonda (Eleanor Lightbody)

By November, all 56 speaking parts were cast as well as hundreds of hand-picked extras, various San orchestras, brass bands and opera singers.

We had had designed and assembled over 1,200 different period costumes to cover our main cast, San guests, nurses, medical staff and attendants for a dozen different San departments. Authentic originals were gathered from Rome and London as well as yards of lace, linen, wool and other period fabrics culled from flea markets, which her army of seamstresses and assistants built into a colossal wardrobe to cover the three seasons of our story: autumn, winter and spring.

We also had the task of building the eccentric San machines. Thanks to Dr. Kellogg’s meticulous documentation we had plenty of reference to his eccentric devices. With a little creative license, I drew cartoons incorporating many of the Doctor’s mechanical excesses, and Brian Morris translated them into functional, and often very beautiful, props. All of these wonderful machines were built in London and shipped to the States. Some were exact replicas, but others, like the “Morriscope” on which Dr. Kellogg examines Will, (“Candidly, Mr. Lightbody, this lump of flesh I see before me is a dangerous weapon,”) were imaginative hybrids, and I can’t honestly attest to their complete scientific plausibility or purpose.

The interiors of the San all had to be built in the studio in North Carolina, but Brian was able to transform a large meeting room at Mohonk into the elegant San lobby, with yards of added mahogany and brass trim, adding a central reservations desk, acidopholous milk bar and stained-glass windows. Mohonk also gave us our dining room, where Will is admonished into “Fletcherizing” his food. (Horace Fletcher had indeed been an associate of Dr. Kellogg, inventing the principle of chewing food thirty-two times, once for every tooth in the mouth. “Nature will castigate those who don’t masticate”. He also said the immortal line, “My stools have no more odor than a hot biscuit”, which I gave to Dr. Kellogg (who himself, was not averse to stealing a line from someone else). Kellogg was in fact at odds with Horace Fletcher on the subject of regularity. Fletcher confided to the Doctor, on a visit to the San, that he suffered from obstinate constipation. The Doctor gave him a laxative and reported, “It gave rise to a stool which astonished him by its loathsomeness”. Hence the resultant line in the film.)

On the stage at the studios in North Carolina, we built a mammoth set to incorporate milk and mud baths, hydriatic percussion, sinusoidal baths, changing rooms, mechanical rooms, surgical offices, a Fecal Analysis Room, corridors and San bedrooms. By building it all together as one composite set, it gave us a great fluidity of camera movement and great flexibility for Peter Biziou’s light. On the back lot of the studios we recreated Battle Creek (“Cereal Bowl Of The World”) and the Post Tavern (named after C.W. Post, the first breakfast food tycoon, who once was a charity patient in the Kellogg kitchens. It was there that he saw the Doctor’s cereal coffee being made, and so he pinched the idea and eventually marketed a similar product. Kellogg was non-plussed by this particular plagiarism — one of many— as he hadn’t thought much of his own coffee, calling it “a very poor substitute for a very poor thing”. Post, however, sold a ton a day of his version, making him the first breakfast millionaire).

Battle Creek, Michigan: ‘Cereal bowl of the world’. Or more accurately, the back-lot of the studios in Wilmington, N Carolina.

On the back lot, we also built the “Red Onion Restaurant”, which once existed opposite the real San in Battle Creek, and was referred to by Kellogg as “The Sinners’ Club”, a sort of ‘meat speak-easy’ where errant guests “fell off the peanut wagon”, exhausted by corn mush in gluten gravy, and sneaked away for a juicy pork chop, a cigar and a mug of beer. The crew were also going a little sir crazy themselves.

Wilmington is a one horse town and, as usual, the long hours, the three bars and two restaurants had outstayed their welcome after many long months.

In the main, the shooting process was pleasurable considering the large and interweaving story lines that necessitated a chaotic and unwieldy schedule. Sappy as it sounds, Bridget, Mathew, John and Dana were all models of professionalism, making my life very easy as a director.

Tony found his own character, which I went along with. I can’t say I wasn’t nervous about it, but I had written a script truthful to TC Boyle’s outrageous book and so Tony took his cue from that. Tony is one of those actors that you can choreograph a complete scene before he arrives and he loves the challenge of making it work —other actors prefer to block out the scene themselves in rehearsal. Both approaches have their supporters.

Tony has the ability to rehearse a scene and then on take five, suddenly like a champion javelin thrower take it to a place you never imagined it could go. (Whether this place is the ‘right’ place depends on the director’s faith in Tony’s genius. To extend the javelin metaphor: is it a world record or did the judge just get impaled?)

Tony reads and rereads his script a thousand times, sitting in his hotel room, late at night. He was always word perfect which is very unusual among film actors. Off set and on he always had a rosy demeanor and swashbuckling attitude that disguised hours of reading and preperation. I think that Hopkins and Hackman are similar as actors. Both have avuncular personalities and superb technical skills, but also both possess scarier hidden demons that they keep carefully hidden only to summon up for their work.

Tony was the darling of the British crew, sharing as they did, many an in-joke from past movies. Much has been written about Tony and his dedication to Alcoholics Anonymous. His easy bonhomie and friendly shenanigans with the crew—hamming it up, sharing their jokes and licorice all-sorts (in a bag taped to the front of the camera dolly,) hid a much darker side which, thankfully, we didn’t witness on Wellville. Tony’s own secret shadows of the soul are now kept in check with enormous discipline.

And with such sober unnoted passion

He did behave his anger.

Timon of Athens—III/V

As usual we were attempting a much bigger film than our budget allowed and the producer, Bobby Colesberry, got paler by the day as we stretched our budget to breaking point. I had previously made The Commitments with Beacon, the same independent production company who were bankrolling Wellville. In my experience and observation of the variously talented and sensitive businessmen who continue to turn up with their carrier-bags full of money for films (as the old song goes, “…dirty money comes from who knows where, keeps the wheels a running, keeps the kids from starvin’. Oh Lord I’ll take the dirty money, I swear that I don’t care.”) is that the congeniality of these so called “financiers” towards the production is inversely proportionate to the difference between the pre-sales (foreign distributors buying the film before its finished for a set price) and the cost of the movie. Give me a major studio anytime compared to the skittish independent cowboys who only serve to vitiate our work. Working with a major studio, as a filmmaker, at least you know going in that they will hang on to the fiscal trapeze however many summersaults you perform and when it comes to catching you…sometimes they even do. My advice to new filmmakers is to make sure you’re well paid for stripping your soul raw making your movie because, sure as hell, you’re not going to see any profits.—and if you’re movie bombs here won’t be anyone around to tend your wounds. Even if your film is a hit, profit participation will take a long time to enjoy —if ever— and in the independent sector, after ten years your film will almost always be owned by a different company than the one you made it with. The negative of a film is made of Kryponite —absolutely indestructible — hidden as it is in an Iowa salt mine and, curiously never ever gets lost —unlike the filing cabinets containing your profit participation contracts which almost always do.

Our final challenge read simply enough: to burn down the venerable San. My producer, Bob Colesberry, with guile equal to Goodloe Bender’s, had worked on the owners of Mohonk Mountain House. However, despite our claims of some expertise in this area —having torched many a church in Mississippi —they were understandably not over-receptive to any suggestion of simulating the conflagration anywhere near their magnificent hotel. The proud old building had, after all, survived since 1869 without suffering the fate of most of the other wooden structures in America of that period. Curiously, although the hotel boasted ‘138 working fireplaces’, the mere lighting of a cigarette in the wrong areas could set off vicious fire alarms that could be heard in Poughkeepsie. We therefore built a full-size replica of the front of the San in Wilmington, which we duly burned to the ground.

Filming began in November of ’93 and finished in February of the following year. It took 62 shooting days to complete.

Alan Parker, Los Angeles, September ’94

Afterwards

John Neville and Judy Dench in Hamlet

John Neville passed away in 2011. He was a doyen of British Shakespearian theatre including many memorable roles at the Old Vic including, as legend has it, the definitive Richard II. In 1956 he and Richard Burton performed a memorable double act alternating the roles of Othello and Iago. John told the famous story of how, before a matinee performance he and Burton had gone out for a boozy lunch at the Ivy restaurant, “staggering out of the restaurant a little worse for wear, we returned to the theatre and both played Iago. The audience noticed nothing unusual, and nor, in the state we were in, did we.”

John Neville and Richard Burton play Othello and Iago and Iago and Othello, and Iago and Iago.

It’s true to say that few novelists ever say nice things about the way their books are made into films. However, the ever gracious Tom Boyle did write this following piece about The Road to Wellville which first appeared in Zoetrope: All Story magazine. It’s only fitting that he should have the last word.

Text © Alan Parker. All photos © Beacon Communications, Inc. Stills photography: Merrick Morton. Cinematographer: Peter Biziou.

CHARLIE OSSINING GOES DOWNTOWN, THANKS TO ALAN PARKER

By T. Coraghessan Boyle

How many happy novelists are there out there in the evergreen forests, the cornfields, the walk-ups and condos of this grand and spacious country? Not many. Novelists are by nature disaffected, terminally unhappy, misanthropic and irremediably bitter over their thwarted desire to conquer all before them. That’s why they became novelists in the first place – for revenge. Now take this very small set of happy novelists (most or all of whom are drugged) and separate out the subset of novelists who have had one or more of their novels made into films. How many of them are happy? The answer is, one: me.

Early on, because of my peculiar brand of obstinacy and my own Napoleonic delusions, I refused to have anything to do with the film industry – I wasn’t gong to carry anybody’s jockstrap, by God. Also, I understood something intuitively that seems to escape many of my contemporaries: novelists write novels, and directors direct films. All well and good. As a novelist, you have two options: to sell the film rights of a given book, thereby relinquishing control over the film version, or retain the rights and have your widow toss the manuscript atop your coffin as they lower you into the earth. (No fear: as soon as your seventy-eight years are up there’ll be competing film versions of all your books, early and late, and nobody to say different. Look at Wharton. Austen, James. James, for Christ’s sake!)

I did go to lunch, though (I lived in LA, so lunch was close; plus I was hungry). I made friends in the industry – Phil Kaufman, among them, who remains a good friend – and I acquired (was acquired by) Evarts Ziegler, the most astonishing and classically exuberant agent in the universe. Typical conversation, regarding the nine-hundredth deal for my novel, Water Music (which, incidentally, has been under perpetual option since its publication in 1982):

ZIG (in his been-there-and-back rasp)

Tom! So and so’s hot on this, and they really want to get together with you!

ME

Great. Tell him my demands are simple. I want to direct, star, and play all the principal female roles in drag.

All this by way of saying that I’m not a player. Not then, not now. Never have been, never will be. So when Alan Parker made his offer on my 1993 novel, The Road to Wellville, I was pleased to meet with him and his producers for a celebratory dinner, presided over by our mutual agents, Jane Sindell and Sally Willcox, of Creative Artists Agency, because there was never any question of my participation. Alan, at that point, already knew much ore more than I did about the subject (turn of the century Battle Creek, Michigan, and Dr John Harvey Kellogg’s famed sanitarium). The subject lit Alan up, and he is a brilliant and tireless researcher. He liked me because I’d written a book he loved and given him the story and setting for the film to follow The Commitments, in his career, and I liked him because he’d made at least three of my all-time favourite movies.

By way of history, which many readers will know, Alan wrote the script from my novel himself and Columbia released the picture in the fall of 1994, starring Anthony Hopkins as Dr Kellogg; Matthew Broderick as Will Lightbody; Bidget Fonda as his wife, Eleanor; John Cusack as the hustler-entrepreneur, Charlie Ossining; and Dana Carvey as Dr Kellogg’s deranged, filth-smeared alcoholic son, George. An amazing cast, really. In my estimation, that is. And as I’ve suggested above, I am partisan. Very much so.

As readers may also know, the movie was not a commercial success in this country. I can’t really fathom why. It is very, very funny – and funny in a new and bizarre way. It’s almost as if Alan had made his version of a Fellini film, when you consider all the wonderful grotesques he employs, the zany Nino-Rota-on-speed score, and the perverse hilarity supplied by the novel (sexiest enema scene in the movie history, but then, of course, I can’t think of much competition in that particular category). I maybe I can fathom why the movie didn’t do much business here – it’s something new, not at all what the audience, dulled by sitcoms, expects comedy to be. Too hip for the room? On the other hand, I can see that the film may have its limitations, too. It seems to compressed, breathless, as if the filmmaker needed more space (time, that is), and the studio squeezed him. (I don’t know if this is the fact – I never discussed it with Alan.) And maybe, just maybe – and you’d never expect a novelist to say this – it’s too true to the book and its five hundred pages of complications.

A film is not a book – it’s a film. I understand that. Why does everybody else seem to have so many problems with so basic a concept. Eternally, the film critics contrast Alan’s version with mine. This is a fruitless exercise. To my mind, Alan’s film is daring, experimental, ballsy – it’s something new for Christ’s sake, new!… and killingly funny.The first time I saw it was at a screening before the premiere (Alan: joyous, sailing, ushering us in), and the audience howled and slobbered and got right down on the floor and chewed the legs off the seats. All right, granted, it was a sectarian audience, but the same thing happened at the premiere and at the two subsequent showings where I saw the film with our fellow real people, men and women, the unwashed and unannointed. This is a funny film, folks, and every time I see it (I think we’re sitting at six now) I develop those laughing pains in the back of the skull, twin jabs right there in the cerebral cortex deprived of oxygen from too much laughing. How could anybody criticize that?

It’s difficult to describe to the non-novelist just how thrilling it is to see or hear your work interpreted by someone else, particularly if that someone else is a master like Alan Parker. There have been two short films of my stories – Greg Beeman’s The Big Garage; and Damian Harris’s Greasy Lake – and both dug into those stories and revealed something new about them. And there have been many, many live performances of my stories and audiotapes, too, and each gives me – the disaffected, misanthropic non-player – a rush of pure joy and connection: somebody else is singing my song. I’m happy. I’m very happy. Of course, talk to me after the first butchering of my work up there for all to see.

And this is an important consideration, perhaps the most important consideration for the novelist contemplating the film version of his or her book: publicity. The film, good or bad, in most cases will help sell books. We – we – novelists – want one thing only, aside, of course, from aesthetic gratification, and that is to get the word out, to get our books across, ours and nobody else’s. (And here I have to adduce the case of my hero, the greatest marketing genius of all time, Mao Tse-tung: if you don’t have two copies of the little red book, you die.) So I’m happy. Did I mention that?