The life of david gale

The making of the film

For twenty-odd years now, I have written the notes on the making of my films. Originally, it was a knee-jerk reaction to the practice of distributors handing out unhelpful hyperbole – hastily assembled info often written by someone who wasn’t even around when we made the movie – usually dished up on a few sheets of stapled-together paper. Equally, as has often been pointed out to me by my journalist friends, perhaps a few sheets of superficial information are exactly what journalists and film writers require – especially if they don’t like the movie! (They sarcastically tease me that when it comes to me spouting on about my movie, they find that a list of cast and crew credits, preferably spelled correctly – plus a tote bag full of CDs, T- shirts, baseball caps and passes for the Universal Studios tour – to be imminently more preferable.

But anyway, I persevere. Not least of all, because something of what I’ve scribbled down here, as candid as prudence allows, might be of help to anyone interested in how we made the film and, more importantly perhaps – considering the subject matter – why we made it.

This film began with a strike – well, at least the threat of one. There I was in September of 2000 tapping away at my keyboard working on a novel when my co-producer (and wife), Lisa Moran, gently pointed out that the threatened strike by SAG and the Writers Guild could mean that I might not be making a film for a whole year. Maybe longer, as the strike, set for June 2001, was nine months away, and who knew how long it would last — such was the intransigence of the conflicting factions, everyone was predicting a long fight. In fact, as a member of the Writers Guild, I might not even be allowed to write either. Consequently I joined the frantic scramble, along with many of my fellow filmmakers, to seek out (always difficult) and get financed (always impossible) what became known as a “pre-strike” movie. In short: get your movie made before the sword of Damocles falls and the factory gates slam shut for who knows how long.

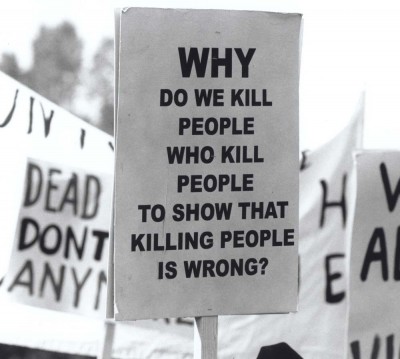

Lisa was the first to read Charles Randolph’s script, The Life of David Gale. And, like her, I then read it in one sitting, astonished that such a well-written, page-turner of a script hadn’t already been made. Although the script — an original story, a fiction —most certainly had an important political issue at its core that I strongly responded to, it was also a terrific thriller. It had been gathering dust on a Warner Bros. shelf since it was written in 1998 when Nicolas Cage’s production company commissioned it and the script was now in “turn-around” from Warners. Charles Randolph, originally from Texas, had written it while still performing his day job as a professor of philosophy at a Vienna university. I flew to Los Angeles and had lunch with Nicolas Cage, who I knew, having directed him as a very young man in Birdy (1984). He had two ‘pre-strike’ films lined up as an actor and so he graciously passed the David Gale baton over to me. Stacey Snider, the boss of Universal, with whom I had a long-term deal, read it overnight and phoned to say that she wanted to make it and proceeded to secure the rights. We immediately left for Texas for a preliminary recce — as always, on films at this stage, paid for on my credit card — studios being too canny to commit their dollars too readily, especially with a strike looming. I knew Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana well, having filmed there, but although I had visited Texas many times, I had never visited Austin, where our story is principally set. I also visited the Ellis Unit prison in East Texas where Death Row is set in our story and “The Walls” unit in downtown Huntsville where all executions in the state take place — at this time I was merely an observer, viewing from outside the high, red brick walls for which the prison is nicknamed. Later, I would become much more familiar with what goes on inside.  Returning to London, Stacey Snider called me to say that she thought it more prudent if we went “post-strike.” Her theory being that the casting cupboard was becoming somewhat bare as actors, like everyone else, were scrambling and signing up for one, even two films, before the feared June strike deadline. She also contended that the studio/unions strike negotiations were going well and there was increasing optimism that there wouldn’t even be a strike. Ever the skeptical pragmatist in dealing with studios, who are traditionally judicious with the truth, I agreed. To be more accurate, I had no say in the matter, anyway. And so the key crew members who had committed themselves to the film and to myself, all found ourselves on “hiatus”, still without pay, for another five months until the strike was finally resolved. However, time is never wasted on the preparation of a film and the breather allowed time to work with Charles on honing the script, to meet with actors and to briefly return to my novel. In May the studio released a small amount of money so that we could return to Texas for a more thorough recce. The Governor’s office and the Texas Film Commission were most helpful in easing the way for us to approach the prison authorities — the Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Returning to London, Stacey Snider called me to say that she thought it more prudent if we went “post-strike.” Her theory being that the casting cupboard was becoming somewhat bare as actors, like everyone else, were scrambling and signing up for one, even two films, before the feared June strike deadline. She also contended that the studio/unions strike negotiations were going well and there was increasing optimism that there wouldn’t even be a strike. Ever the skeptical pragmatist in dealing with studios, who are traditionally judicious with the truth, I agreed. To be more accurate, I had no say in the matter, anyway. And so the key crew members who had committed themselves to the film and to myself, all found ourselves on “hiatus”, still without pay, for another five months until the strike was finally resolved. However, time is never wasted on the preparation of a film and the breather allowed time to work with Charles on honing the script, to meet with actors and to briefly return to my novel. In May the studio released a small amount of money so that we could return to Texas for a more thorough recce. The Governor’s office and the Texas Film Commission were most helpful in easing the way for us to approach the prison authorities — the Texas Department of Criminal Justice

The “Walls” prison in downtown Huntsville, Walker County, East Texas, is where all executions in Texas have taken place over two centuries. On this trip, we had the advantage of being shown around by the TDCJ’s public relations man, Larry Fitzgerald. An avuncular, articulate, forthright man, Fitzgerald is largely responsible for the open, “nothing to hide” attitude of the TDCJ when it comes to Huntsville being dubbed “the execution capital of America.” Charged as he is with the task of patiently and continually explaining to the world’s media exactly what they’re up to down in Texas, with their proclivity for weekly executions, I felt that I already knew him, having seen him featured in the numerous documentaries that I had viewed during our research. He and Warden Neill Hodges courteously showed us around the death chamber, housed in the low 1950s-style “Building #1835” that is nestled within the high brick walls and approached by a neat garden with the occasional sprouting flower. Matter-of-factly they showed us the cells where the inmates spend their last hours after they are transferred from Death Row at the Polunsky Unit an hour away. A plastic curtain intersected the row of seven cells (apparently useful for when they have two executions on the same day and need to isolate the condemned men). Walking past the beige, tiled shower (the coroner appreciates a clean corpse), we were guided through the door at the end into the green brick death chamber. As we stood around the hospital gurney, the warden, who oversees and attends all executions, courteously and matter-of-factly explained the “tie down” procedure, last words, and the clinically lethal injection of the three poisons: sodium thiopental (lethal dose – sedates person); pancuronium bromide (collapses diaphragm and lungs); potassium chloride (stops the heart). Death occurs in seven to ten minutes – maybe ten at most, he said. Larry explained how the proceedings are viewed, through a partition window, by the crime victim’s family (since 1996), members of the press and next to them, in a segregated room, the condemned inmate’s family can watch. The actual executioner is secreted in a tiny adjacent cubicle where he injects the poisons along three tubes poking through a square hole in the wall. (Since the American Medical Association barred physicians from taking part in executions, this task is now performed by a prison employee – often by an ex-military paramedic. The attending physician only confirms time of death.) I had thought that I could never even enter this room, if the opportunity ever arose, creepy as I thought it to be. But I soon found myself inured to the function of this place as I chatted away amiably with the same matter-of-factness as Warden Hodges. Engaging the warden in conversations as to the effectiveness or morality of the death penalty was short. He is a career correctional officer and notions of an alternative such as “life without parole” are an anathema to him – someone who has spent his life looking after violent prisoners. As for Larry Fitzgerald, who has witnessed over one hundred executions, and who personally knew many of the inmates put to death, if asked, he always shrugs his shoulders philosophically: “It’s the law. And whilst it’s the law, we do the best we can.”  We then visited Terrell Prison unit where Death Row is now housed. Until 1965, Death Row was at the Walls unit in Huntsville, when it was moved to the Ellis Unit, 12 miles north of town. Then in 1998, was the first escape from Death Row in 64 years occurred when inmate Martin Gurule fled from an Ellis work detail and scaled two fences of razor wire, his body protected by thick layers of newspapers strapped around his body. He had, however, taken a bullet on escape and a week later was found dead in a nearby creek, the sodden newspapers having dragged him to the bottom. Consequently, in 1999 Death Row was moved to the more secure Terrell Unit in Livingstone. To be accurate, at the time we visited it was called “Terrell” but it is now renamed the Polunsky Unit. When it was built in 1993, this ultra-modern prison was named, as tradition has it, after an ex-Chairman of the Texas Board of Criminal Justice – in this case, Charles T. Terrell. However, when Death Row was moved there six years later, they didn’t consult with Mr. Terrell, who took umbrage because, ironically, of late he has had a change of heart about the death penalty, particularly as it pertains to the potential executions of innocents. He now favors a policy of life without parole. As the prison he built was now home to the most conspicuous and certainly the busiest, Death Row in the U.S. he was displeased with it being synonymous with his family name and so he politely asked them to change it. It is now called the Polunsky Unit, not surprisingly, after the next Chairman of the TBCJ, Allan B. Polunsky, who apparently has no such qualms about the death penalty. The first view of Terrell/Polunsky is quite startling. Housing 2,800 inmates, its massive, no-nonsense architecture, surrounded by clipped lawns and neat flower beds behind the acres of razor wire, it give it the appearance of a very modern automobile factory. Passing through the many layers of security along the razor wire tunnels, it’s very impressive as the numerous automatic “salle-portes” zip open and whoosh shut – very shut – behind you. Through smoked glass I could see a control center that had more video screens than a CNN newsroom. We passed a reassuring sign that said, “Hostages will not exit.” The shiny floors and pristine walls belie the fact that Polunsky is considered one of the toughest prisons in Texas. It’s certainly the most secure. There are 450 prisoners currently awaiting execution here, in a special wing. Curiously, in spite of all the high-tech gadgetry on display, the six-foot by ten-foot cells, with solid doors, have no air conditioning. Since the 1998 Ellis breakout the TDCJ is not messing around. The work program has been suspended and Death Row prisoners now reside in solitary confinement for twenty-three hours a day, and all communication with other inmates is forbidden. For our visit, as always, the prison officer showing us around – on this occasion Major Tim Lester, the unit’s “family liaison officer” — was extremely courteous and candid, as he led us deep into the prison. It was a quiet day, he told us. “You should have been here last week, our busiest day — Mother’s Day.” In the visitation area families were chatting away to the Death Row inmates, communicating through the thick glass via telephone handsets, while children ran around and their parents worked the soft drink and snack vending machines. For a few dollars, they could even have a Polaroid taken against the armor-plated glass with their condemned relative, courtesy of the TDCJ. It’s all very ordered and matter of fact. As we left and looked back at the Death Row wing, with its narrow, four-foot by six-inch window slats, the duty officer said, “Give them a wave, there’s four hundred pairs of eyes looking at you right now. Back in Austin, I began looking at possible locations with my production designer, Geoffrey Kirkland, and art director, Jennifer Williams. There are 70,000 undergrads at universities in and around Austin and their culture dominates the city and its economy (as evidenced by the hundreds of music bars on 6th Street. I liked Austin. Not quite the “San Francisco of the South” as it is sometimes described, but an interesting, sophisticated and tolerant city. We also traveled further afield, looking at small towns just outside Austin. I particularly liked Taylor and Elgin where we saw many interesting possibilities. We also returned to the Ellis Unit, built in 1963 (2300 inmates), which had originally housed Death Row for over 30 years until the move to Polunsky. Charles Randolph had originally written our story with Ellis in mind and we were now allowed inside. We were escorted across the Japanese bridge and water feature to the visitation rooms, which were exactly as I had seen them in many documentaries and which we would replicate for our film. We would, however, be needing permission to film the exterior of the prison, beyond the high security areas. As always, everyone was extremely courteous, as we were shown through the central spine of the prison amongst the mass of prisoners. Our visit culminated with lunch in the canteen served by the less vilolent inmates.

We then visited Terrell Prison unit where Death Row is now housed. Until 1965, Death Row was at the Walls unit in Huntsville, when it was moved to the Ellis Unit, 12 miles north of town. Then in 1998, was the first escape from Death Row in 64 years occurred when inmate Martin Gurule fled from an Ellis work detail and scaled two fences of razor wire, his body protected by thick layers of newspapers strapped around his body. He had, however, taken a bullet on escape and a week later was found dead in a nearby creek, the sodden newspapers having dragged him to the bottom. Consequently, in 1999 Death Row was moved to the more secure Terrell Unit in Livingstone. To be accurate, at the time we visited it was called “Terrell” but it is now renamed the Polunsky Unit. When it was built in 1993, this ultra-modern prison was named, as tradition has it, after an ex-Chairman of the Texas Board of Criminal Justice – in this case, Charles T. Terrell. However, when Death Row was moved there six years later, they didn’t consult with Mr. Terrell, who took umbrage because, ironically, of late he has had a change of heart about the death penalty, particularly as it pertains to the potential executions of innocents. He now favors a policy of life without parole. As the prison he built was now home to the most conspicuous and certainly the busiest, Death Row in the U.S. he was displeased with it being synonymous with his family name and so he politely asked them to change it. It is now called the Polunsky Unit, not surprisingly, after the next Chairman of the TBCJ, Allan B. Polunsky, who apparently has no such qualms about the death penalty. The first view of Terrell/Polunsky is quite startling. Housing 2,800 inmates, its massive, no-nonsense architecture, surrounded by clipped lawns and neat flower beds behind the acres of razor wire, it give it the appearance of a very modern automobile factory. Passing through the many layers of security along the razor wire tunnels, it’s very impressive as the numerous automatic “salle-portes” zip open and whoosh shut – very shut – behind you. Through smoked glass I could see a control center that had more video screens than a CNN newsroom. We passed a reassuring sign that said, “Hostages will not exit.” The shiny floors and pristine walls belie the fact that Polunsky is considered one of the toughest prisons in Texas. It’s certainly the most secure. There are 450 prisoners currently awaiting execution here, in a special wing. Curiously, in spite of all the high-tech gadgetry on display, the six-foot by ten-foot cells, with solid doors, have no air conditioning. Since the 1998 Ellis breakout the TDCJ is not messing around. The work program has been suspended and Death Row prisoners now reside in solitary confinement for twenty-three hours a day, and all communication with other inmates is forbidden. For our visit, as always, the prison officer showing us around – on this occasion Major Tim Lester, the unit’s “family liaison officer” — was extremely courteous and candid, as he led us deep into the prison. It was a quiet day, he told us. “You should have been here last week, our busiest day — Mother’s Day.” In the visitation area families were chatting away to the Death Row inmates, communicating through the thick glass via telephone handsets, while children ran around and their parents worked the soft drink and snack vending machines. For a few dollars, they could even have a Polaroid taken against the armor-plated glass with their condemned relative, courtesy of the TDCJ. It’s all very ordered and matter of fact. As we left and looked back at the Death Row wing, with its narrow, four-foot by six-inch window slats, the duty officer said, “Give them a wave, there’s four hundred pairs of eyes looking at you right now. Back in Austin, I began looking at possible locations with my production designer, Geoffrey Kirkland, and art director, Jennifer Williams. There are 70,000 undergrads at universities in and around Austin and their culture dominates the city and its economy (as evidenced by the hundreds of music bars on 6th Street. I liked Austin. Not quite the “San Francisco of the South” as it is sometimes described, but an interesting, sophisticated and tolerant city. We also traveled further afield, looking at small towns just outside Austin. I particularly liked Taylor and Elgin where we saw many interesting possibilities. We also returned to the Ellis Unit, built in 1963 (2300 inmates), which had originally housed Death Row for over 30 years until the move to Polunsky. Charles Randolph had originally written our story with Ellis in mind and we were now allowed inside. We were escorted across the Japanese bridge and water feature to the visitation rooms, which were exactly as I had seen them in many documentaries and which we would replicate for our film. We would, however, be needing permission to film the exterior of the prison, beyond the high security areas. As always, everyone was extremely courteous, as we were shown through the central spine of the prison amongst the mass of prisoners. Our visit culminated with lunch in the canteen served by the less vilolent inmates.  I returned to Los Angeles briefly on my way to China where I was serving on the jury of the Shanghai International Film Festival. Whilst in China, Kevin Spacey called me to say that he had read the script and very much wanted to do the film. This was great news, not least of all because with Kevin on board the studio would now officially “green-light” the film and all of us who had worked on the film for seven months would now get paid. This took yet another month to achieve when we were officially green-lit (August 12th) and all finally decamped to Austin to begin the film proper. Since January, Kate Winslet had been calling me regularly, expressing her desire to play Elizabeth (Bitsey) Bloom in the movie. Now we were in a position to offer her the part and Kate began working with the esteemed dialect coach, Carla Meyer, on her East Coast accent. Laura Linney had agreed to play Constance and we had the heart of our cast. I had been casting in L.A. for many weeks to fill the subsidiary parts with casting directors Juliet Taylor and Howard Feuer. I had also been very encouraged by my local casting sessions in Texas, as actors from Austin, Houston, Dallas and San Antonio came in to read for me. Also I held a mammoth “open call” at Austin’s St. Edwards Catholic University for anyone who wanted to be in the movie. Apart from finding wonderful extras for the film, I love having open calls because there is always the chance that someone new will spring out from the hundreds of hopefuls that file through the doors. A lot of the smaller parts were cast in this way. I had cast Gabriel Mann in Los Angeles, after seeing hundreds of young actors for the role of Zack — both famous names and wannabes. Gabe has a lovely, ingenuous quality – always likeable whilst playing a character far too smart for his own good. Matt Craven (Dusty) and Leon Rippy (Gale’s lawyer, Braxton Belyeu) I had also cast in L.A. – both of them terrific actors – and total gentlemen. Rhona Mitra I had cast in London. Almost everyone else I had cast locally from our numerous sessions in Austin. September saw the crew grow from the handful of us, who had worked on the film for nearly a year, to over two hundred. In 2000, the City of Austin and the Austin Film Society had taken over the private section of the disused Robert Mueller Municipal Airport, turning it into a de facto film studio. Our production offices had dug in at the old control tower and Geoffrey Kirkland began to build our sets in the disused hangars. We built an entire prison complex to replicate the Ellis visitation rooms and entrance lobby and corridors of the prison as well as a number of other interiors, such as Constance’s house. Our schedule had been designed around around the two stories in our script. David and Constance’s back story was to be filmed in the first six weeks, overlapping for a few days with the Kevin/Kate interviews and then for the last six weeks we planned to shoot Bitsey and Zack’s present-day story. The last weeks of preparation were crazed as we completed sets, nailed down locations, screen-tested make up, hair and costumes. Michael Seresin, my cinematographer and colleague for thirty years, together with the camera operators Mike Proudfoot and Ted Adcock, walked the course with me as we always do, pacing sets and locations, scripts in hand trying to figure out at least some of it in advance —before the madness of filming began. Kevin, Laura and I also read through the script many times, smoothing out any hiccups and making sure that the film forming in all our heads was not just a good one, but the same one. Finally we arrived at our first day of filming, October 5th, a year and a month since I had first read the script. We started with Gale’s TV debate with the governor. Michael Crabtree, who plays the Texas Governor, I had cast locally.— avoiding the temptation to cast a George W. Bush look-alike. Although our fictional character in the film does share many of the then U.S. President’s views, being as he is a staunch proponent of the death penalty, having authorized 146 executions whilst Governor of Texas. The State Legislature in Texas, curiously, only sits every two years or so. (The very definition of less government. A hundred years ago it was muted that they meet every five years, encouraging the concept of no government.) Whilst in session, filmmakers, with our attendant traffic-snarling mobile circus, were understandably unwelcome at the Capitol. Consequently, it was difficult to get permission to use the building for filming.. After many refusals, the Governor’s office once again intervened, and we were granted permission to shoot Laura’s rally speech there. The offices of DeathWatch, the abolitionist organization for which Constance and Gale are the principal activists, we had set in Taylor, a small, decaying town, just outside Austin. I had found a number of locations there — it’s almost a movie studio back-lot, with its host of boarded up buildings and empty streets — typical of many, once vibrant, but now abandoned, small towns in the rural South. However, most of our locations were in Austin and close to our base — all within comfortable striking distance of the crew hotels. (The crew was predominantly drawn from London, New York, Los Angeles and of course, many from Austin.) We had planned a number of scenes at the new Austin International Airport, but just one month after September 11th, permissions to film were, understandably, promptly withdrawn. As fortune would have it, Austin’s previous airport was abandoned, but thankfully still intact, as no one had yet figured out what to do with it. Everything had been stripped out, but the shell was there and Geoffrey Kirkland and Jennifer Williams set about refurbishing and transforming it into a modern airport. The university in Austin was most helpful. I can’t mention its name because although they gave us permission to film there, they were quite starchy about being represented in our film. They allowed us the use of the campus with the proviso that we never identified it by name. They were particularly adamant that I kept the well-known campus tower out of my shots, which frankly from a compositional point of view was an easy task – with our wide-screen anamorphic format I couldn’t get it in the frame anyway. The logic for their earnest desire for anonymity was never clear (as anonymous as one of the largest, most well-known campuses in the U.S. could be, anyway). It is consequently oddly referred to as “The University of Austin” in our film.

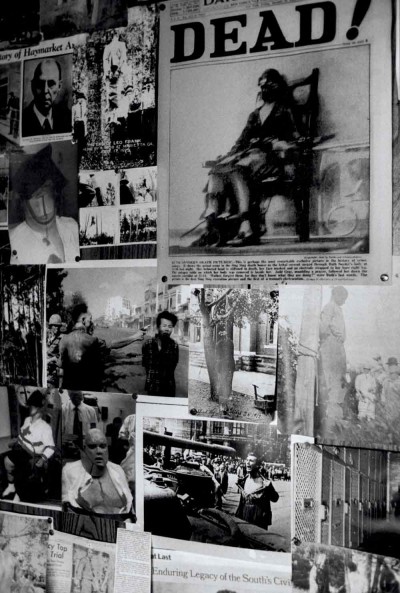

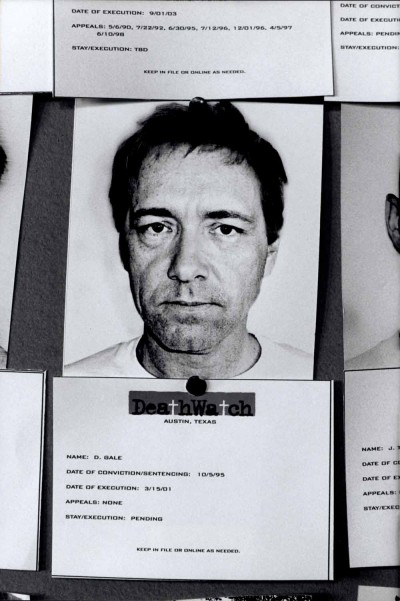

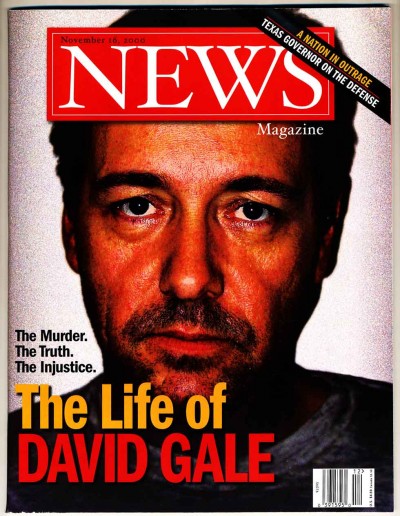

I returned to Los Angeles briefly on my way to China where I was serving on the jury of the Shanghai International Film Festival. Whilst in China, Kevin Spacey called me to say that he had read the script and very much wanted to do the film. This was great news, not least of all because with Kevin on board the studio would now officially “green-light” the film and all of us who had worked on the film for seven months would now get paid. This took yet another month to achieve when we were officially green-lit (August 12th) and all finally decamped to Austin to begin the film proper. Since January, Kate Winslet had been calling me regularly, expressing her desire to play Elizabeth (Bitsey) Bloom in the movie. Now we were in a position to offer her the part and Kate began working with the esteemed dialect coach, Carla Meyer, on her East Coast accent. Laura Linney had agreed to play Constance and we had the heart of our cast. I had been casting in L.A. for many weeks to fill the subsidiary parts with casting directors Juliet Taylor and Howard Feuer. I had also been very encouraged by my local casting sessions in Texas, as actors from Austin, Houston, Dallas and San Antonio came in to read for me. Also I held a mammoth “open call” at Austin’s St. Edwards Catholic University for anyone who wanted to be in the movie. Apart from finding wonderful extras for the film, I love having open calls because there is always the chance that someone new will spring out from the hundreds of hopefuls that file through the doors. A lot of the smaller parts were cast in this way. I had cast Gabriel Mann in Los Angeles, after seeing hundreds of young actors for the role of Zack — both famous names and wannabes. Gabe has a lovely, ingenuous quality – always likeable whilst playing a character far too smart for his own good. Matt Craven (Dusty) and Leon Rippy (Gale’s lawyer, Braxton Belyeu) I had also cast in L.A. – both of them terrific actors – and total gentlemen. Rhona Mitra I had cast in London. Almost everyone else I had cast locally from our numerous sessions in Austin. September saw the crew grow from the handful of us, who had worked on the film for nearly a year, to over two hundred. In 2000, the City of Austin and the Austin Film Society had taken over the private section of the disused Robert Mueller Municipal Airport, turning it into a de facto film studio. Our production offices had dug in at the old control tower and Geoffrey Kirkland began to build our sets in the disused hangars. We built an entire prison complex to replicate the Ellis visitation rooms and entrance lobby and corridors of the prison as well as a number of other interiors, such as Constance’s house. Our schedule had been designed around around the two stories in our script. David and Constance’s back story was to be filmed in the first six weeks, overlapping for a few days with the Kevin/Kate interviews and then for the last six weeks we planned to shoot Bitsey and Zack’s present-day story. The last weeks of preparation were crazed as we completed sets, nailed down locations, screen-tested make up, hair and costumes. Michael Seresin, my cinematographer and colleague for thirty years, together with the camera operators Mike Proudfoot and Ted Adcock, walked the course with me as we always do, pacing sets and locations, scripts in hand trying to figure out at least some of it in advance —before the madness of filming began. Kevin, Laura and I also read through the script many times, smoothing out any hiccups and making sure that the film forming in all our heads was not just a good one, but the same one. Finally we arrived at our first day of filming, October 5th, a year and a month since I had first read the script. We started with Gale’s TV debate with the governor. Michael Crabtree, who plays the Texas Governor, I had cast locally.— avoiding the temptation to cast a George W. Bush look-alike. Although our fictional character in the film does share many of the then U.S. President’s views, being as he is a staunch proponent of the death penalty, having authorized 146 executions whilst Governor of Texas. The State Legislature in Texas, curiously, only sits every two years or so. (The very definition of less government. A hundred years ago it was muted that they meet every five years, encouraging the concept of no government.) Whilst in session, filmmakers, with our attendant traffic-snarling mobile circus, were understandably unwelcome at the Capitol. Consequently, it was difficult to get permission to use the building for filming.. After many refusals, the Governor’s office once again intervened, and we were granted permission to shoot Laura’s rally speech there. The offices of DeathWatch, the abolitionist organization for which Constance and Gale are the principal activists, we had set in Taylor, a small, decaying town, just outside Austin. I had found a number of locations there — it’s almost a movie studio back-lot, with its host of boarded up buildings and empty streets — typical of many, once vibrant, but now abandoned, small towns in the rural South. However, most of our locations were in Austin and close to our base — all within comfortable striking distance of the crew hotels. (The crew was predominantly drawn from London, New York, Los Angeles and of course, many from Austin.) We had planned a number of scenes at the new Austin International Airport, but just one month after September 11th, permissions to film were, understandably, promptly withdrawn. As fortune would have it, Austin’s previous airport was abandoned, but thankfully still intact, as no one had yet figured out what to do with it. Everything had been stripped out, but the shell was there and Geoffrey Kirkland and Jennifer Williams set about refurbishing and transforming it into a modern airport. The university in Austin was most helpful. I can’t mention its name because although they gave us permission to film there, they were quite starchy about being represented in our film. They allowed us the use of the campus with the proviso that we never identified it by name. They were particularly adamant that I kept the well-known campus tower out of my shots, which frankly from a compositional point of view was an easy task – with our wide-screen anamorphic format I couldn’t get it in the frame anyway. The logic for their earnest desire for anonymity was never clear (as anonymous as one of the largest, most well-known campuses in the U.S. could be, anyway). It is consequently oddly referred to as “The University of Austin” in our film.  The students certainly made us welcome. Kevin waded into the twenty-deep student crowd of his screaming fans, shaking hands and answering their mobile phones. The great thing about Kevin, his acting brilliance aside, is that he wears his movie celebrity so comfortably. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he actually enjoys it. Not for him the baseball cap pulled over his face as he dashes to his limo after finishing a scene. Kevin won’t leave until every autograph is signed. His scenes in the lecture hall had the assembled kids (all UT students) spellbound as they forgot that that they were actually making a movie. It was as though they had lucked out and caught a class by the coolest lecturer on campus. Also Charles’s script helped. It’s no mean feat, in today’s cinema, to promulgate the ethical importance of Lacan and also keep your audience on the end of their seats for two hour. The hardest scenes to shoot were those involving Contances’s (Laura) death involving, as it did, the real danger of aspyxiation. As with the replication of any death scene, the crew were extra nervous and diligent, and the scenes were shot slowly with great care and an ever present para-medic.

The students certainly made us welcome. Kevin waded into the twenty-deep student crowd of his screaming fans, shaking hands and answering their mobile phones. The great thing about Kevin, his acting brilliance aside, is that he wears his movie celebrity so comfortably. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he actually enjoys it. Not for him the baseball cap pulled over his face as he dashes to his limo after finishing a scene. Kevin won’t leave until every autograph is signed. His scenes in the lecture hall had the assembled kids (all UT students) spellbound as they forgot that that they were actually making a movie. It was as though they had lucked out and caught a class by the coolest lecturer on campus. Also Charles’s script helped. It’s no mean feat, in today’s cinema, to promulgate the ethical importance of Lacan and also keep your audience on the end of their seats for two hour. The hardest scenes to shoot were those involving Contances’s (Laura) death involving, as it did, the real danger of aspyxiation. As with the replication of any death scene, the crew were extra nervous and diligent, and the scenes were shot slowly with great care and an ever present para-medic.

Kate Winslet (Bitsey) with bag on her head, attended to by make-up supervisor Sarah Monzani and prop master Don Miloyevich.

We were approaching the halfway mark of the shoot when it was nearing time for Kate Winslet to arrive from London. She had been working on her accent for some months now with her dialect coach. One day in the office Lisa got a call from one of Kate’s Los Angeles agents. The obnoxious person said she was new in the office and that “there was a problem with Kate’s (previously agreed) arrival dates.” Lisa, needless to say, was displeased, only to be answered with a screech of laughter. It was Kate herself on the phone, trying out her new American accent, convincingly impersonating a Hollywood agent. Kate arrived, as scheduled of course and we immediately read through the scenes she would be doing with both Kevin and Gabe and I fielded her many questions. The first work she had to do was the “interview” scenes with Kevin in our giant Ellis Unit Death Row set. Geoffrey Kirkland, in the name of authenticity, had conscientiously, but not overly practically, constructed the whole thing for real out of solid steel and bulletproof glass. It was a complete replica — so effective that neither the camera assistants nor I could get to Kevin, trapped as he was in maximum security. We solved the problem by cutting a trap door in the steel wall so that I could more easily talk to Kevin, rather than through a six-inch by three-foot wire mesh grill. Kevin’s last scene was shot on 6th Street where David staggers into the crowds, drunkenly ranting about Aristotle. We wrapped at midnight and our proximity to the local bars allowed for an enjoyable farewell party for him. We then embarked on Kate and Gabe’s part of our film as Bitsey begins to unravel Gale’s story to get closer to the truth. I was blessed with many great actors on this film. Double Oscar-winner that he is, Kevin’s reputation goes before him. A consummate actor, he is unafraid of revealing the flaws in a character. He takes these imperfections by the scruff of the neck and throws them right back at you, newly formed and noble. He surprised me with what he did every day. Laura is the actor loved by other actors and has also been nominated for an Academy Award. Everything she does is infused with her own humility – an anomaly in today’s “look at me – aren’t I great’ acting styles. She is the most generous actor I have ever worked with. But she’s also smart, of course. Her strong theater background allows her to act brilliantly while seemingly giving absolutely everything to the other actors and yet, when you see the dailies and the finished film, she still ends up stealing her scenes. That’s clever. Amongst a great cast, I’d single out Matt Craven (Dusty), Gabe Mann (Zack), Leon Rippy, (Belyeu) and Jim Beaver (Duke Grover, the prison PR man) – all of them a pleasure to watch and, importantly, a delight to have on a film set. Which brings me to Kate Winslet. At the risk of the hyperbole I reproved of at the beginning of this piece —if I ever work with a better actress, or a nicer one, it could only be Laura Linney. Kate had wanted to do this part for so long and fought to do it even when the studio, at first, saw her only as an English rose (in corsets), albeit one who had been nominated for two Academy Awards before she was twenty (and played an American in Titanic, the most successful film of all time). We worked very well together — it was telepathic almost — and she’s fun. The hard-bitten American and English crew also admired her. In between shots, she would unselfishly help them technically at every point. Sorry about this love-fest stuff. Whether anyone else likes what we did is of course up to him or her, but with an industry plagued by egocentric actors, it’s good to mention a cast who got on with their jobs and behaved, well, just like the rest of the crew. It’s such a calm and pleasant way to make a movie. Then we were hit by tornado. We were filming with Gabe and Kate in a diner on the outskirts of Austin. We carried on filming as the weather reports frantically bounced around the assistant directors’ walkie-talkies as the storm got closer and closer. At noon it became as black as night, and the storm ripped into the electricians’ lights outside, shattering the two-inch thick fresnel lenses as the giant steel lights were snapped from their harnesses and bounced down Highway 183. K.C., the first assistant director and the crew’s designated DGA safety officer, made the decision to abandon filming as we were surrounded on three sides by the sheet glass windows of Jim’s Diner. We crowded together in the small inner kitchen – over fifty of us – as the tornado grew in intensity. We put Kate, clutching her baby, into the inner food storage room for extra safety. After two hours the eye of the storm had passed and we limped back to the hotel, floating through the flooded highways. It was then time to move the entire unit to Huntsville for the Walls and Ellis scenes. Curiously, I didn’t feel so intimidated as I had on my previous visits. Standing outside the thirty foot high, three-foot thick red brick walls of Huntsville prison with the whole film circus of 50 vehicles, two helicopters and a crew of two hundred (dressed in their L.L. Bean combat gear), I felt like Attila the Hun at the gates of Rome. Huntsville is a typical East Texas small town. (Apart from the mammoth statue of Sam Houston that you see as you drive into town. It’s an extraordinary structure – part Soviet statuary, part Colonel Sanders.) Huntsville is also also a “company” town – its principal industry being “the correctional business.” In Walker County alone, where Huntsville is situated, there are seven large prisons housing 13,000 inmates and employing 6,000 local security and support staff. Because of Huntsville’s high profile as an execution center, the town is quite used to large-scale attention from the media. Consequently, Larry Fitzgerald of the TDCJ was undaunted by our presence and smoothed the way as we shot our scenes with our helicopters buzzing overhead — the hundreds of inmates inside the prison courtyard shouting and waving at the helicopters, possibly hoping for a ride and an early release.  Larry Fitzgerald was having dinner at a local restaurant during filming when a friend came up to his table. “Hell of a noise out there today, Larry,” he said. “Must have been a big one. Who got executed?” The worlds of film and reality had collided. Larry generously told me this story as a compliment to our recreation. No one died in our version. On December 22nd, after 61 days of filming, right on schedule and miraculously on budget, we completed filming in Texas. The crew could now go home for Christmas. Returning to London with 300,000 feet of film, Gerry Hambling and I began the editing process. Gerry has cut every one of my films. He’s a great editor to which his many awards testify, but he’s not what you’d call fast. He shares with Michael Kahn (Steven Spielberg’s editor) the distinction of being the last editors to cut on film rather than computer, and these great masters cannot be hurried. We still had to complete the Barcelona sections of the film and the Puccini “Turandot” opera scene. We recorded Liù’s aria at Abbey Road Studios with soprano Janis Kelly and an 80-piece orchestra. In Barcelona we shot Dusty’s and Sharon’s (Gale’s wife) scenes and went into the Barcelona opera house to shoot the reverses, principally the audience scenes. We weren’t allowed to use the stage area, which was in the midst of another production, and so, back at Shepperton, Jennifer Williams, our Art Director, recreated our version of “Turandot.” The final sound mix was done with my long-time colleague, Andy Nelson, at Fox studios in Los Angeles. Frankly, it’s a miracle that this film even got made in today’s climate, with the ever-present pressure on studios to deliver mega-buck successes to their owners. Our film is a thriller with a polemical heart. I am very grateful to Stacey Snider and to Universal for having had the courage to make it. Alan Parker, November 2002

Larry Fitzgerald was having dinner at a local restaurant during filming when a friend came up to his table. “Hell of a noise out there today, Larry,” he said. “Must have been a big one. Who got executed?” The worlds of film and reality had collided. Larry generously told me this story as a compliment to our recreation. No one died in our version. On December 22nd, after 61 days of filming, right on schedule and miraculously on budget, we completed filming in Texas. The crew could now go home for Christmas. Returning to London with 300,000 feet of film, Gerry Hambling and I began the editing process. Gerry has cut every one of my films. He’s a great editor to which his many awards testify, but he’s not what you’d call fast. He shares with Michael Kahn (Steven Spielberg’s editor) the distinction of being the last editors to cut on film rather than computer, and these great masters cannot be hurried. We still had to complete the Barcelona sections of the film and the Puccini “Turandot” opera scene. We recorded Liù’s aria at Abbey Road Studios with soprano Janis Kelly and an 80-piece orchestra. In Barcelona we shot Dusty’s and Sharon’s (Gale’s wife) scenes and went into the Barcelona opera house to shoot the reverses, principally the audience scenes. We weren’t allowed to use the stage area, which was in the midst of another production, and so, back at Shepperton, Jennifer Williams, our Art Director, recreated our version of “Turandot.” The final sound mix was done with my long-time colleague, Andy Nelson, at Fox studios in Los Angeles. Frankly, it’s a miracle that this film even got made in today’s climate, with the ever-present pressure on studios to deliver mega-buck successes to their owners. Our film is a thriller with a polemical heart. I am very grateful to Stacey Snider and to Universal for having had the courage to make it. Alan Parker, November 2002

Music

The first thing that we completed musically was the song that Alex had been working on – “Another Bleeding Heart” – and which he then took into the studio. Jake wrote the string sections for the song and we were suddenly off on a musical experiment. I have to say now, that as proud as I am of my sons’ accomplishments, I would always be far too selfish with regard to my film to mess it up with notions of nepotism. But, little by little, we started to nudge towards a score that I felt was fresh and original, and one that I couldn’t possibly replicate with a more starry-named composer. Universal were very patient during this period: “Who’s doing the score, Alan?” they asked weekly. “I’m experimenting,” I would answer. “All will be clear when I show you the finished film.” Alex and Jake would immediately work on each scene as it came off the Moviola. Jake took the scenes that needed more traditional, orchestral pieces and Alex worked on the rhythmically driven ‘thriller’ scenes. It was a completely organic process – the music was created at exactly the same time as we cut the scenes, something that I had never been able to do before on my films. They adapted their work as we cut: Alex, in his back room studio, layering dozens of complex tracks to affect the scenes and Jake, working to picture on his Clavinova, adjusting his music bar by bar. There came a point when the film required them to work together – something they hadn’t done for some time. Alex’s contemporary multi-tracks had to fuse with Jake’s classical themes. The cues they had named from the script, so Jake’s “Lacan” theme (named from the French philosopher in David’s first lecture) suddenly became musically and nominally “Ominous Lacan” as Jake’s cello pieces fused with Alex’s less elegantly entitled cues, i.e. “Ominous House Vibe.” The very titles themselves are a reflection of their different musical educations. The two of them worked through the night to work and rework their stuff for my film: Jake’s pieces for “Almost Martyrs” and “Huntsville Epitaph” and Alex’s pieces for “Shack 2 Cell,” “Dusty’s Cabin” and “Media Frenzy.” I doubt that any director ever got so much work out of his composers, especially as they hadn’t been paid a cent at this point. (We were still in the experimental zone, as far as Universal was concerned.) And, as closely entwined as we are as a family – and also, it has to be said, as opinionated as we usually all are with regard to our different musical tastes – miraculously we got through it without a single argument. Finally, Universal saw and approved the film with its (up to now, electronically recorded) score. We then had to finish the music. At Abbey Road in Studio 1, Jake – who had orchestrated his pieces for a 70-person orchestra – received a round of applause at the end of the sessions from the collected players (not usually known for their altruism). Alex worked away in Studio 3, laying down the dozens of tracks he had created himself in his backroom studio and augmenting them with live musicians.

The first thing that we completed musically was the song that Alex had been working on – “Another Bleeding Heart” – and which he then took into the studio. Jake wrote the string sections for the song and we were suddenly off on a musical experiment. I have to say now, that as proud as I am of my sons’ accomplishments, I would always be far too selfish with regard to my film to mess it up with notions of nepotism. But, little by little, we started to nudge towards a score that I felt was fresh and original, and one that I couldn’t possibly replicate with a more starry-named composer. Universal were very patient during this period: “Who’s doing the score, Alan?” they asked weekly. “I’m experimenting,” I would answer. “All will be clear when I show you the finished film.” Alex and Jake would immediately work on each scene as it came off the Moviola. Jake took the scenes that needed more traditional, orchestral pieces and Alex worked on the rhythmically driven ‘thriller’ scenes. It was a completely organic process – the music was created at exactly the same time as we cut the scenes, something that I had never been able to do before on my films. They adapted their work as we cut: Alex, in his back room studio, layering dozens of complex tracks to affect the scenes and Jake, working to picture on his Clavinova, adjusting his music bar by bar. There came a point when the film required them to work together – something they hadn’t done for some time. Alex’s contemporary multi-tracks had to fuse with Jake’s classical themes. The cues they had named from the script, so Jake’s “Lacan” theme (named from the French philosopher in David’s first lecture) suddenly became musically and nominally “Ominous Lacan” as Jake’s cello pieces fused with Alex’s less elegantly entitled cues, i.e. “Ominous House Vibe.” The very titles themselves are a reflection of their different musical educations. The two of them worked through the night to work and rework their stuff for my film: Jake’s pieces for “Almost Martyrs” and “Huntsville Epitaph” and Alex’s pieces for “Shack 2 Cell,” “Dusty’s Cabin” and “Media Frenzy.” I doubt that any director ever got so much work out of his composers, especially as they hadn’t been paid a cent at this point. (We were still in the experimental zone, as far as Universal was concerned.) And, as closely entwined as we are as a family – and also, it has to be said, as opinionated as we usually all are with regard to our different musical tastes – miraculously we got through it without a single argument. Finally, Universal saw and approved the film with its (up to now, electronically recorded) score. We then had to finish the music. At Abbey Road in Studio 1, Jake – who had orchestrated his pieces for a 70-person orchestra – received a round of applause at the end of the sessions from the collected players (not usually known for their altruism). Alex worked away in Studio 3, laying down the dozens of tracks he had created himself in his backroom studio and augmenting them with live musicians.

Afterwards

Needless to say that, family connections aside, I am immensely proud of the score Alex and Jake did for my film. A weird phenomenon occurred with the music in that a cue from the film — an orchestral piece by Jake, entitled “Almost Martyrs” —became used as the music for the trailers of The Artist, Munich, The Iron Lady, World Trade Center. This happened to us before with a Randy Edelman cue from Come See the Paradise called “Fire in the Theatre” which found it’s way on to the trailers of a dozen or more different movies I suppose it’s flattering but I wish they’d use their own music to advertise their films.

After, Afterwards

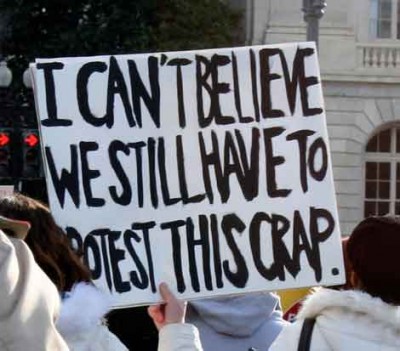

The death penalty debate continues in the United States. There were 37 executions in the US in 2008, the lowest number since 1994. In 2011, there were 43 executions across 13 states. In 2011, the US was the only G8 country in the Western Hemisphere still practising Capital Punishment.

The death penalty debate continues in the United States. There were 37 executions in the US in 2008, the lowest number since 1994. In 2011, there were 43 executions across 13 states. In 2011, the US was the only G8 country in the Western Hemisphere still practising Capital Punishment.

All text © Alan Parker. All photos © Universal Pictures, Inc. Stills photography: David Appleby. Cinematographer: Michael Seresin