The Commitments

The making of the film by Alan Parker

Some time after The Commitments came out, Johnny Murphy who had played ‘Joey the Lips’ was doing a play in Cork. He had his usual couple of Guinness’s in the pub before the matinee and strolled back to the theater. As he passed the local Post Office, four guys in ski masks rushed out with shotguns and lump hammers, having just robbed the place. Johnny, quite naturally, froze in his tracks, scared out of his wits. As he put it: ”Holy Jesus, I thought, and I stood there like the snowman in ‘Meet me in St Louis’ as they rushed by me with alarm bells ringing and money flying everywhere.” Suddenly, as one of the guys in the ski masks was ducking into the getaway car, he caught sight of Johnny standing there and shouted, “Look it’s Joey! It’s Joey the Lips from the Commitments!” The villain calmly walked back from the car, tucked the shotgun under his arm, and vigorously pumped Johnny’s hand saying “How’s it goin’ Joey? That was a fucking grand fillum.” Then he jumped into the car that sped off as the police cars screamed around the corner in pursuit. Johnny, mouth open, still speechless, turned around and scurried back to the pub for another Guinness.

The first time I read Roddy Doyle’s slender volume, “The Commitments”, I was only a couple of pages in before I found myself laughing out loud. The book was all dialogue with very little description, but by the use this wonderful language, and almost nothing but language, in a few lines he was able to make his characters as vivid and strong as a dozen pages of purple Joycian prose. As they say in Dublin, he cuts the bollix. Roddy writes as he’s heard it: street sharp, gutsy and true.

The first time I read Roddy Doyle’s slender volume, “The Commitments”, I was only a couple of pages in before I found myself laughing out loud. The book was all dialogue with very little description, but by the use this wonderful language, and almost nothing but language, in a few lines he was able to make his characters as vivid and strong as a dozen pages of purple Joycian prose. As they say in Dublin, he cuts the bollix. Roddy writes as he’s heard it: street sharp, gutsy and true.

I had been introduced to the book in 1989 by Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais who had been employed to write a screenplay. For some time I had been nagging myself to make a film closer to home and although Dublin isn’t London it’s a lot closer to home than Los Angeles. Once I’d agreed to do this “nice little film”, to my surprise I discovered that there were no less than eight credited producers. Having just finished Come see the Paradise where I had just one producer, this was quite new to me. The original project had two producers: Lynda Myles (who had originally optioned the book) and her partner in the project, Roger Randall Cutler, who had found the funding for the option and an early script, originally written by Roddy Doyle. The major finance came from a new independent company in Los Angeles called Beacon, which was run by an old acquaintance of mine, the producer and writer, Armyan Bernstein. There were also three co-producers, two more executive producers and my line producer David Wimbury who actually did all the work. It’s fair to say that I had complete autonomy and none of these people interfered — they were mostly absent and let me get on with making the actual movie. But as I had noted on a sign I had pinned on the production office wall: “Eight producers who are 88 percent nice, congenial, helpful and pleasant but 12 percent irritating, adds up to one producer who is a complete asshole.”

Roddy Doyle, Dublin, 1990

The film was comfortably financed by pre-sales, which were secured at Cannes where I did my tap dancing act for the foreign distributors.

In June of ’90 I arrived in Dublin to begin preparations for the movie. Jet-lagged from Los Angeles and armed with sponge ear plugs, I immediately began the auditions process, listening to 64 bands at ten minute intervals playing everything from heavy metal to hip hop, and folk to funk. We dubbed the next three days “Deaf Aid”; such was the level of noise from the earnest musicians. Ros and John Hubbard, the casting directors, had spent the previous two months scouring the Dublin clubs to pick out likely candidates. The Hubbards had assiduously gone about their task — even going on the wagon (a not inconsiderable sacrifice in Ireland) in order for them to visit six pubs a night to hear the bands. Ros Hubbard was mother hen to the burgeoning cast of hopefuls with a deft combination of kindness and devastating Dublin frankness —as in. “Excuse me lovey, is that lipstick or herpes you have there on your top lip.”

After each audition I read a short scene with each band member. The Waterfront nightclub on the Liffey quayside, which we had taken over for the auditions, was very short of space and so I had to do the readings cramped in a greasey-tiled kitchen behind the bar.

I had said from the outset, rather rashly, that in our search for the Commitments members I would consider anyone who sang or played a musical instrument. It was pointed out to me that there were as many as 1200 bands playing in Dublin, which is extraordinary in a city of just over a million people. There was a little Irish blarney attached to this, however, as I discovered that many of the young musicians often play in three or four bands at a time and “The Boneshakers” this week can inexplicably be called “Hep Cat Huey” the next. Each evening a different pub offered us up yet another band belting away in the cramped upstairs rooms. They say forming a band in Dublin is one thing, but finding somewhere to play is a little more difficult. Also on every street corner there seemed to be a busker who was dutifully dragged in to audition. Many reasons are put forward for the music explosion in Ireland. The international success of performers like U2, Sinéad O’Connor, Van Morrison and Bob Geldof are obvious beacons for young Dubliners. Ireland also has the youngest population in Europe and (in 1990) the high unemployment amongst young people is an important factor in why so many struggle to buy their guitars and form their garage bands as a way of gaining some dignity for the present and hope for a future.

Also, in order to cast our net as widely as possible, we had organized an open casting call at the Mansion House (town hall) where we invited anyone in Dublin who wanted to be considered for the film. Over 1500 young hopefuls turned up reading a page of the script and singing and playing everything from guitars to tin whistles, banjos to bagpipes (quite a miraculous turnout considering Ireland was doing rather well in the World Cup at the time, consequently bringing Dublin to a halt). The truth is, of course, if you ask absolutely anyone to sing in Ireland they’ll gladly oblige —often quite beautifully and sometimes even without a glass of Guinness in their hand.

Also, in order to cast our net as widely as possible, we had organized an open casting call at the Mansion House (town hall) where we invited anyone in Dublin who wanted to be considered for the film. Over 1500 young hopefuls turned up reading a page of the script and singing and playing everything from guitars to tin whistles, banjos to bagpipes (quite a miraculous turnout considering Ireland was doing rather well in the World Cup at the time, consequently bringing Dublin to a halt). The truth is, of course, if you ask absolutely anyone to sing in Ireland they’ll gladly oblige —often quite beautifully and sometimes even without a glass of Guinness in their hand.

I also saw all of the established young actors in Dublin, particularly those who were also musicians. I had decided that we wouldn’t cheat any of the instruments or singing and that we would attempt to do our music live to remain faithful to the gritty truth in Roddy’s original characters. In the book and the film the band members take their first steps hesitantly — being downright awful in their early rehearsals, but gradually improving, culminating in their brief success at the end of our story. Our musicians therefore had to have a certain degree of competence in order to be able to bridge this transition from bad to good. The conventional wisdom being that it was a lot easier for a good musician to play badly than the converse!

I also had to find our locations. Roddy Doyle had set his story in a mythical “Barrytown”, obviously based on Kilbarrack, the working class estate on the Northside of Dublin where he worked as a school teacher. I had discussed with Roddy the possibilities of moving the locations of our film to different parts of Dublin, still being truthful to the origins of our story but taking advantage of other locations including the inner city which offered more cinematic possibilities. Location hunting can be difficult at the best of times but Dublin proved to be vexing as my Production Designer, Brian Morris, and I tried to strike a balance between the bland 50’s boredom of the neat Northside housing estates and the older city centre.

It was our intention at all times to avoid the picture postcard locales traditionally associated with Ireland and show a contemporary, urban world a little different from viridescent, romantic notions normally associated with films about Ireland. Gradually we put together a patchwork of places, streets and buildings of a world we could see but not find in one place. Not for the first time, I found myself climbing walls, avoiding guard dogs and knocking on doors that the occupants seemed chary about opening. In Dublin, it’s not unusual to climb a ladder to get from one part of a garden to another, and I put this in the script at Joey’s Mother’s house.

By mid-July I had pored over the 30 hours of casting tapes (we had seen over 3000 hopefuls) and whittled down the possible ‘Commitments’ to a hundred. Backed by our session band they each came along and performed a couple of our chosen songs. It was the first time that many of them had ever performed with a live band and it was quite moving to see some of the kids, who had come off the street at the open call, singing their hearts out as they struggled through the classic Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin songs.

I also had to select the 60’s soul songs that the ‘Commitments’ would perform. I didn’t want to use anything that had been featured prominently in other films and, most importantly, I had to be faithful to the ‘soul line’ that Jimmy Rabbitte, our lead character, would approve of. For the previous two months I had been listening to as many songs as I could from the back catalogues – including many old favorites of mine on the Stax and Atlantic labels. I narrowed the choices down from an original 300 to 75 which we put into rehearsal with the session band we had assembled in Dublin. Paul Bushnell, a young Dublin musician, was the bass player in our session band and he’d also arranged the possible songs for me. I was very impressed by his musicianship and, more importantly, his patience and kindness as he gently nursed the nervous auditioners through their chosen numbers. Although he’d never worked on a film before, I decided to make him the band musical director and for the next five months he was never far from my side.

Andrew Strong (Deco Cuffe), Dublin

At the end of July we had reworked and rehearsed over seventy songs and I had whittled down the casting to three possibilities for each role. One afternoon, whilst watching the session band perform the last of the songs to be considered, a young man called Andrew Strong came in. He was sixteen years old and the son of Rob Strong who had been helping out with temporary vocals for the session band. Young Andrew stood at the mic and belted into “Mustang Sally”. I couldn’t believe his mature voice and such extraordinary confidence from someone so young. His voice was exactly as Roddy had described it in the book: “… a real deep growl that scraped against the tongue and throat on the way out”. I pulled him to one side and asked if I could read with him. “Read?” he said, with some fear, as if I was a spy from the Board of Education. I explained, that ‘Read’, meant going through the pages of the script, – just a few lines for me to get an idea of his acting abilities. Sitting there on two plastic fold-up chairs, in the corner of the band rehearsal room, I read and re-read the Deco part with Andrew. It was obvious that he was closer to Otis than he was De Niro, but it seemed that I had found the Deco for our film. He didn’t resemble the description in the book, Andrew not being conventionally handsome —closer in looks to Charles Laughton than Bryan Ferry, but boy, could he sing. I thought that as long as I had that voice, with a little patience and considerable rehearsal we could also turn him into an actor. That was the idea anyway.

I sorted through the various permutations of our casting, juggling all the possibilities in a giant photographic chessboard on my hotel room floor. Finally I decided on the chosen twelve Commitments. Ten of them were musicians, only the voluble Bronagh Gallagher (Bernie) and Johnny Murphy (Joey) had ever acted before. As each one of them were informed that they’d got the parts their reactions varied from an astonished “Jeez, I can’t believe it” to the blasé, “Yeah, I know. Me mam already told me”.

Many of the cast lived nomadic, rather dubious lifestyles, and so it was hard to keep tabs on them — we had to issue mobile phones to those cast members who didn’t have permanent phones. Even those who did were hard to pin down : “Do you have an answering machine?” “Yeah, me Grannie.”

Each of the thousands of kids who had come in to the casting had such honesty and spirit that it had made the whole process pleasurable and consequently extra difficult to leave anyone out. However, apart from our performed songs we also had another thirty music cues in the film and so we were able to involve many of those who didn’t quite make it as a “Commitment”. I wanted to capture the many textures that make Dublin so rich in music, from the Uileann pipe player to a Cajun version of Elvis, and these are interwoven throughout the film. (In the finished film there are 68 different musical cues including 52 different songs).

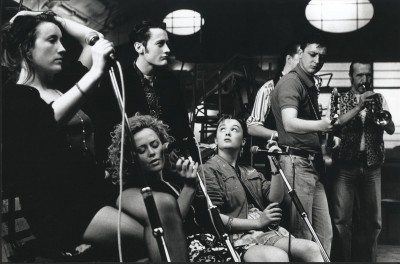

Angeline Ball (Imelda Quirke), Maria Doyle (Natalie Murphy), Bronagh Gallagher(Bernie McGloughin)

Our next task was rehearsing the script and recording the music. At the beginning of August, we assembled the cast for the first time in the production office. They stood around in the kitchen, sipping their coffees, in complete silence. They were all very nervous. Even in a city as small as Dublin, and in a somewhat, (but not much) smaller music community, curiously, none of them knew one another.

For the next five weeks we had dramatic rehearsals in the mornings and music rehearsals in the afternoons. Any kind of rehearsal is a luxury on most films, but on this one it was a necessity. I was able to work with them collectively and in smaller groups, as they became familiar with the script and their characters. This not only prepared the young actors for the weeks ahead this also enabled each different department to come and watch each scene to work out the complexities of sound and picture that we would encounter. In most scenes all twelve characters are interacting with one another and with the music they are playing, so these rehearsals were invaluable for everyone. One of the helpful devices I used was to swap the lines around – the girls playing the boy’s parts. This was very useful as the girls, in the main, were better actors and it enabled the lads to hear their own lines read with different (and mostly better) intonation than they might employ. Being musicians they all had great ‘ears’ and so the musicality of a line could be remembered by heart, even if their own natural acting wasn’t quite up to snuff. I continued rehearsing throughout the shooting, each Sunday, our day off, to keep everyone sharp and prepare them for each week of filming ahead of us. Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais were able to watch rehearsals and it was a great opportunity to adjust and rewrite as the script evolved so that it fitted the character we’d cast more snugly. Roddy had written a draft screenplay before Dick and Ian did theirs and although the book was always our touchstone the script developed organically during rehearsal and through the shooting period.

Maria Doyle, Angeline Ball, Robert Arkins, Bronagh Gallagher, Ken McCluskey and Johnny Murphy, Ricardo’s Snooker Hall, Dublin

Our music priority was to lay down the basic tracks for the twenty-four chosen performed songs. We had decided to use a new system for shooting and recording the music which had never been used before on a film. Most film music from “Singing In The Rain” to MTV uses pre-recorded tracks and vocals which are played back as the camera takes up different positions with the artists miming. I wanted to capture the reality of the rehearsals and performing by recording the vocals live on set. This is very difficult as modern film requires many different angles to be covered and a constant sound track is needed in order for the finished edited scene to match cut by cut. We used a new system of out-of-phase speakers which enabled us to play the pre-recorded constant backing tracks at maximum volume on set to give us a live performance atmosphere for the vocalists to sing to. Each vocal was then recorded live onto a twenty-four track recorder that was on set with us. Because of the out-of-phase speakers the vocals could be recorded cleanly, as they were filmed, for re-mixing later. This allowed us the technical precision needed for a complicated cut but gave us the truth, energy and spirit of a live performance. It also enabled us to interweave dramatic dialogue with the songs.

By the end of the month we had rehearsed each scene in the film over and over until our ten musicians had become actors and our two actors had become musicians and all of them had become an accomplished ensemble theatrical group. By the time we were ready to film, all the songs could be performed by the cast and we could run through the whole script, from beginning to end, in one stretch, just like a play.

We began shooting on August 27th. The film took 53 days to complete at 44 different locations around Dublin. It went so smoothly I didn’t even keep a diary.

Afterwards

I have not had a more enjoyable time filming than when I made this movie in the daily, hilarious company of these brilliant kids. There is an old maxim that says that you don’t have to have a good time in order to make a good movie, very often it’s to the contrary — but some times it helps. Certainly I’ve done films (like Pink Floyd The Wall) that were a less than pleasurable experiences, but during the making of The Commitments, when I woke up each morning I couldn’t wait to get to the set.

Probably of all my films, The Commitments is the most liked — particularly by critics. I think the film captures a litlle of the spirit and spunk of the working class kids in Dublin’s Northside. I also hope it catches some of the wit and wisdom of Roddy Doyle’s original novel. The film probably succeeded because, although it’s set in Dublin, it’s about the hopes and dreams music brings to young kids everywhere, from Finglas to Philadelphia and Memphis to Minsk.

Ironically, the film has its own post script of what happened to each of the band members since The Commitments split up. It’s interesting to see how closely the fate of each of our young actors resembles our fiction.

Michael Aherne (Steven) still plays organ in his local church and is quite outspoken with his right wing views. He took three months leave of absence from his job on the Dublin Corporation to make the film. Michael still works for the city of Dublin as a traffic planner. He is said to be responsible for some of the worst traffic jams in Europe.

Maria, Bronagh and Angeline have all forged successful acting careers. Angeline was the first actress in Ireland to win ‘best actress’ for a movie and a TV drama in the same year. Maria who had originally found fame briefly before The Commitments with the Hothouse Flowers band also successfully continues her music with The Black Velvet Band with her husband Kieren Kennedy.

Glen Hansard (Outspan) had formed his own band ‘The Frames’ before the film began, and he continues as one of Ireland’s best loved singers and songwriters.

Felim Gormley (Dean) was an established session sax player before the film and had already toured with the Rolling Stones and Billy Joel. Robert Arkins (Jimmy Rabitte) was an accomplished musician before the film, with his band Housebroken. Robert had not acted before and I persuaded him to play the lead role of Jimmy Rabitte, the manager of the band and so, in the film, the only exhibition of his musical skills are his lead vocals on ‘Treat her Right’. He continues his musical interests but has shown little enthusiasm for acting.

Dick Massey (Billy) and Ken McCluskey (Derek) have continued for many years touring campuses as ’The Commitments’. The two of them aren’t actually allowed to call themselves ‘The Commitments’ and so on the posters it says above the title, in very small letters, ‘Stars from’. Dave Finnegan and Andrew Strong have all joined the above ‘band’ from time to time when they needed a few bob.

Dick Massey (Billy) and Ken McCluskey (Derek) have continued for many years touring campuses as ’The Commitments’. The two of them aren’t actually allowed to call themselves ‘The Commitments’ and so on the posters it says above the title, in very small letters, ‘Stars from’. Dave Finnegan and Andrew Strong have all joined the above ‘band’ from time to time when they needed a few bob.

Andrew Strong was given the best opportunity for the future with an instant contract from MCA after we finished the film. Perhaps Andrew’s personality was too similar to Deco’s: echoing the scene I put at the end of the movie where he throws a glass of Guinness at the long suffering record producer, played by myself. Whatever the reasons, Andrew’s incredible voice never lived up to its potential.

Dave Finnegan who played Mickah —the bouncer with the most feared forehead on Dublin’s Northside— toured for many years with McCluskey and Massey in their surrogate Commitments band : swallowing the microphone at every manic performance. I don’t know if this diet effected his musical career, but he has since disappeared from the musical scene.

Dave Finnegan who played Mickah —the bouncer with the most feared forehead on Dublin’s Northside— toured for many years with McCluskey and Massey in their surrogate Commitments band : swallowing the microphone at every manic performance. I don’t know if this diet effected his musical career, but he has since disappeared from the musical scene.

Andrea Corr (Sharon Rabbitte)

Andrea Corr who plays Jimmy’s sister Sharon, ironically went on to be the most successful of the cast—and she only had one line “Go and shite.” ‘The Coors’ which she formed with her two sisters, Caroline and Sharon, and brother Jim first performed in public together at our first auditions at The Waterfront. I had also cast Andrea as ‘Juan Peron’s mistress in in Evita.

In the film, I had made much of the ‘enigmatic’ lyrics of the Procul Harem song “Whiter Shade of Pale’. On Evita I was lucky enough to have Gary Brooker playing Peron’s side-kick, Juan Bramuglia. In between shots he mentioned to me that the mysterious lyrics of the song would have achieved more clarity if only the record company —concerned at the length of the song—hadn’t made them cut the one verse that elucidated everything. The entire crew stood in a circle as Gary sung us the secret missing verse.

My mouth by then like cardboard

Seemed to slip straight through my head

So we crash dived very quickly

And attacked the ocean bed

As Jimmy Rabitte would say, “I’m fucked if I know Terry.”

Written to accompany the DVD release

After, Afterwards

Glen Hansard (Outspan)

Glen Hansard went on to star in, and write the music for the film, ‘Once’ with Markéta Irglová. Their song ‘Falling Slowly’ won the Best Song Oscar® and ‘Once’ was adapted into the highly successful Broadway musical, winning 8 Tonys.

Roddy Doyle went on to great success as a novelist. At the outset, with little interest from traditional publishers, he had bravely used his own cash to self-publish the slim volume of ‘The Commitments’ novella -— just three thousand copies under the imprint ‘King Farouk Press”. As word of mouth grew about the slender opus, especially amongst bands, Heinemann snapped it up.

He told me during filming that he had no interest in becoming a full time writer and would never give up being a teacher in Kilbarrack which he, by all accounts, was very good at and which he saw clearly as his vocation. However, his considerable literary talent elbowed out his scholastic ambitions and he gave up teaching a couple of years later: becoming an Irish celebrity, shaving his hair, sporting a diamond ear ring and winning the Booker Prize along the way. The follow up books to The Commitments in the so-called ‘Barrytown trilogy’ were also made into films: The Snapper and The Van, both scripted by Roddy. Anchored as they were in Kilbarrack and, overshadowed by The Commitments, they were both directed by Stephen Frears to no great success.

Dick Clement, Ian La Frenais and myself have had many overtures to put The Commitments film on stage over the years, but Roddy Doyle owned the theatrical rights to his novella in the UK and Ireland and so is putting a version (of the novella, not the film) on stage himself, in the West End, without any of our contributions or (for legal reasons) any references to our film. An Irish journalist friend of mine said that Roddy’s ego had grown bigger than the Irish National Debt, which I thought was very unfair, although the current publicity for the stage production leaves little doubt as to the the possessive credit. I never realized how, for twenty years, the phrase ‘Alan Parker’s The Commitments’ must have driven Roddy nuts.

All text © Alan Parker. All photos © Beacon Entertainment, Inc. Stills photography: David Appleby. Cinematographer: Gale Tattersall