SHOOT THE MOON

The making of the film by Alan Parker

Bo Goldman started out in his career by writing short scripts for PBS in an unheated attic in a rented house on Long Island, which he shared with wife Mab and six children. By day, Bo and Mab ran a fresh fish and home baked bread shop named “Loaves and Fishes’. He was presumably hoping for a miracle or two, which at the time seemed somewhat scarce.

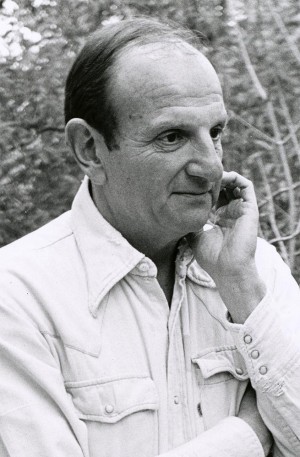

Bo Goldman, one of Hollwood’s finest screen writers

One of the first scripts that Bo tapped out at his typewriter in the garret was called “Switching” the story of the break up of a marriage — a story that ten years later would become Shoot the Moon. In the interim, Bo won a couple of Best Screenplay Oscars® for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Melvin and Howard. The “Switching” screenplay duly made the rounds over the next ten years and although it got Bo a lot of other writing assignments it was always deemed ‘unmakeable’. However, fickle Hollywood executives who are mostly junkies to the audience’s whims, occasionally try to do something a little different. I was duly sent ‘Switching’ by Twentieth Century Fox who, led by Alan Ladd Jr, were flushed and a little stunned by the cosmic financial success of Star Wars and had green lit a number of interesting films. I was preparing Fame at the time and so the script was put on hold, but first met with Diane Keaton who was about to leave for England to start work on Reds for Warren Beatty. I met her for tea at the Algonquin Hotel and her enthusiasm was encouraging, but a long way from commitment, as she was more than a little preoccupied with the radical journalist, Louise Bryant, that she was about to play in Reds. I also met with Meryl Streep who, heavily pregnant, sat on the Fame production office floor as we chatted. After shooting Fame I worked with Bo on the script. He was also writing a film for Mike Nichols at the time and so he worked every other day with me at his rented digs in the Hotel Des Artistes on 67th Street. I must say the collaboration between us was one of the best I’ve ever experienced with another writer. Quite honestly, I hadn’t always gelled with other writers on scripts that weren’t my own. This is largely due to my own impatience, as I like to write the finished draft on all of my films — not just for selfish reasons, but it’s the best way I know how to get the film clearly in my head before I shoot it. My sessions with Bo were a delight. Both married, with ten kids between us, we poured our hearts out to one another like a couple of shrinks lying on couches at opposite ends of the room. Bo continuously and concientiously scribbled down notes at our “sessions” in his indecipherable scrawl. Bo loves the music of everyday words and is so good at capturing the smallest overheard remark that resounds on the page with devastating honesty. Originally the script was set on the east coast in the suburbs of New York, but as the new draft took on its new life, we moved the story to the (then) less familiar Marin County, north of San Francisco. Bo himself had recently moved to St Helena in the Napa Valley and was keen to set our story in the area. Also, it has to be said, it was also because we had spoken to the San Francisco unions about bringing in my key British crew. I had a very uncomfortable time on Fame with the New York unions and, since then, many foreign crews had attempted to work in New York, causing a backlash from the various film unions and technicians, who themselves weren’t allowed to work in Los Angeles, let alone Europe, and so had become more hostile, protective and insular. We also changed the movie’s title. After many weeks of work, Bo thought that the script had changed significantly and deserved its own identity. In passing, he had mentioned the card game of ‘Hearts’ and the phrase ‘shoot the moon’ which meant that you risked all that you have in order to win. I thought it was pretty and also an appropriate metaphor and so ‘Switching’ was finally laid to rest and Shoot the Moon became our movie.. A year had passed since Fox’s original interest and releasing money for pre-production when, as is Hollywood’s wont, Alan Ladd Jr and all his people were abruptly shown the door. Film studios are a bit like banana republics: with the snap of the fingers, managements are unceremoniously evicted and within hours a whole new bunch of people appear from who knows where, becoming instantly ensconced behind the same, recently vacated, desks. Fortunately, Sherry Lansing had taken over as head of production at the studio and remained enthusiastic about the script. Her own autonomy at the time however, sadly didn’t stretch to the $12 million we required for our budget and the men-in-suits above her (whoever they were) gave us the thumbs down. As we had a 100 year old house and film set half built, this presented us with somewhat of a dilemma. For a while Marshall and I thought we we might have to go into the real estate business.

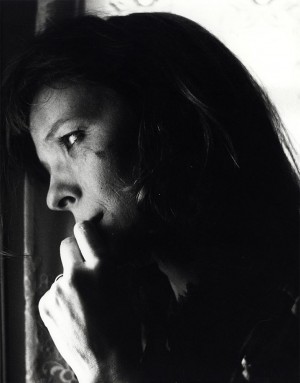

Diane Keaton, Faith Dunlap

Consequently, I found myself having a drink at The Russian Tea Room in New York with David Begelman who was then the head of MGM and for whom I had made Fame, and before that he had been the head of Columbia when we released Midnight Express. The meeting took forty minutes and he agreed to make the film depending on us sticking to the budget and securing Diane Keaton for the lead role. Diane was a highly sought after actress, hot from her Annie Hall Oscar, so it was to our great relief that she finally said yes. My first choice for “George” had been Jack Nicholson but he didn’t feel comfortable with our domestic story and passed. Albert Finney had been a hero of mine since back in England where, as a teenager, I had sat in awe of him playing ‘Luther’ on stage. After Murder on the Orient Express, Albert had taken a six year sabbatical from movies and concentrated on his National Theater work; playing all the great roles from Hamlet to Tamburlaine. However in 1981 he returned to moviemaking and made Shoot the Moon, Loophole, Wolfen and Looker in the same year. He described this burst of activity as “less of a comeback than a shift of interest.” After months of searching, we had found our ideal house on the edge of the San Geronimo Golf Course in northern California. So much of our filming would be based at the single location of the house that Production Designer, Geoffrey Kirkland and I wanted something unusual. However, the derelict 114 year old clapboard ranch house was in less than an ideal spot for filming, situated as it was at the end of the eighth fairway of a golf course, and so we moved it to a 120 acre parcel we’d found a dozen miles away in the Nicasio Valley overlooking the reservoir. The house was cut into four pieces, loaded onto flatbed trucks and transported to the new location — raising a bridge along the way to let the gigantic load through. We built a quarter of a mile road into our valley and re-assembled the house in its new surroundings. In six weeks we had restored, renovated and decorated it. (The pictures here show the before and after.)

The house as we found it, derelict on the San Geronimo golf course. We chopped it up into four pieces and transported it twelve miles to it’s new location.

The house in it’s new location overlooking the reservoir in the Nicasio valley.

We also landscaped the gardens complete with a duck pond; planted olive trees along the entrance road and built a respectable tennis court — en-tout-cas, of course (as mentioned in the script). The house was to act as our studio as well as location and so we also built a number of barns to take our workshops, props, costumes and to allow for catering facilities for seventy crew. What all this effort gave us was the perfect set, in a real location with views out of the windows, complete control and a stunning, uninterrupted 360 degree vista. We were in the middle of all this activity when we heard about the coup at Fox and for a while my producer Alan Marshall and I, not for the first time, were paying the bills ourselves, as we limped on, eventually securing a green light and a much needed cheque from MGM. Juliet Taylor was my Casting Director. I have made many films since with Juliet but not nearly as many as she’s made with Woody Allen, who annually collaborates with her (as she miraculously snares the world’s greatest actors to work on his films for not much more than the price of a couple of dinners at Elaine’s.)

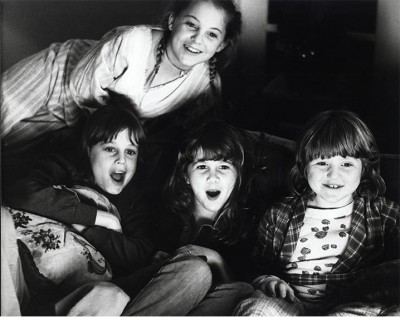

The Dunlap kids: Viveka Davis, Dana Hill, Tracy Gold and Tina Yothers

As usual our casting was exhaustive, throwing the net as widely as possible to find the four kids in the film. I cast in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco taking in the usual agents and also plodding the corridors of the public schools, with my video camera over my shoulder. Viveka Davis (Jill) came from a regular school in Culver City although the other three kids we cast had done some acting work before. The most experienced was Dana Hill who at 14 was a veteran of many TV films; Tracy Gold had a sister who was on TV; and seven year old Tina Yothers had previously shot a few commercials. We also had with us Karen Allen (Sandy), hot foot from England where she had been playing Marion Ravenwood in Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark and Peter Weller who was fresh from Broadway’s Tony winning ‘Sticks and Bones’.  I had arrived in Nicasio with a suitcase full of my own kids clothes. The significance of this, for me, was not evident as I simply thought it would be helpful to have some well worn hand-me-down T shirts and Osh Kosh B’Gosh dungarees, to add a little reality into the movie. The fact that I was subconsciously injecting a little of my own life into the story would be evident to most shrinks but, at the time, not to me. Undoubtedly there were aspects of the marriage in the film which closely echoed my own. Albert, plays a writer in the story not to dissimilar to me and the intimate exploration into the fragile and delicate state of the marriage I found to be curiously close to home.It wasn’t just 120 pages of a script, to be made into a movie, it was like holding up a jagged piece of mirror to my own family and marriage. Up to now, I had only made films about other people’s lives — other people’s predicaments and pain, a world away from my own, and suddenly I was going to work ever day to shoot a fiction that I was also living through. It was an eerie, if not masochistic experience. Kristi Zea, the costume designer had worked with me on Fame and so, like half the female population on the planet, the kids in our story were wearing legwarmers — a fashion that our previous film had begat. Diane’s wardrobe, always a catalyst for a new fashion look (Annie Hall, Reds) was chosen with some care to be ordinary. This isn’t easy with Diane who has a great eye herself (and continues to be the most stylish of American actresses off screen) and however funky and thrift store random we made her clothes, she always looked great. At the first read through of the script, at the San Rafael production offices, Albert did a sort of Natonal Theatre Humphrey Bogart imprsonation. I tactfully asked him if he could do it closer to his own accent – northern California being home to many ex-pat British. He took umbrage at this and I probably got off on the wrong foot with him. At the start of each of my films I have always written a letter to the crew to accompany the first day’s call-sheet. Here’s the one from Shoot the Moon:

I had arrived in Nicasio with a suitcase full of my own kids clothes. The significance of this, for me, was not evident as I simply thought it would be helpful to have some well worn hand-me-down T shirts and Osh Kosh B’Gosh dungarees, to add a little reality into the movie. The fact that I was subconsciously injecting a little of my own life into the story would be evident to most shrinks but, at the time, not to me. Undoubtedly there were aspects of the marriage in the film which closely echoed my own. Albert, plays a writer in the story not to dissimilar to me and the intimate exploration into the fragile and delicate state of the marriage I found to be curiously close to home.It wasn’t just 120 pages of a script, to be made into a movie, it was like holding up a jagged piece of mirror to my own family and marriage. Up to now, I had only made films about other people’s lives — other people’s predicaments and pain, a world away from my own, and suddenly I was going to work ever day to shoot a fiction that I was also living through. It was an eerie, if not masochistic experience. Kristi Zea, the costume designer had worked with me on Fame and so, like half the female population on the planet, the kids in our story were wearing legwarmers — a fashion that our previous film had begat. Diane’s wardrobe, always a catalyst for a new fashion look (Annie Hall, Reds) was chosen with some care to be ordinary. This isn’t easy with Diane who has a great eye herself (and continues to be the most stylish of American actresses off screen) and however funky and thrift store random we made her clothes, she always looked great. At the first read through of the script, at the San Rafael production offices, Albert did a sort of Natonal Theatre Humphrey Bogart imprsonation. I tactfully asked him if he could do it closer to his own accent – northern California being home to many ex-pat British. He took umbrage at this and I probably got off on the wrong foot with him. At the start of each of my films I have always written a letter to the crew to accompany the first day’s call-sheet. Here’s the one from Shoot the Moon:

It was a great luxury to film so many scenes at the same location. Normally we are shooting on the run — our mobile army tearing across town, often trying to fit in too many locations on a single day. Settled as we were in our tranquil spot, high in the Nicasio Valley, if we got a little behind we could always come back the next day to finish a scene. A constant irritation to myself and other directors is the film “call-sheet”, which carries the production office ‘wish-list’ as to what can be achieved that day. On every film these overly ambitious scene lists are always accompanied, at the bottom of the page, with the lovely phrase: “Time Permitting”. On a film set, time never permits. No matter what the film is, the crew is always in overload and there’s never, ever enough time.

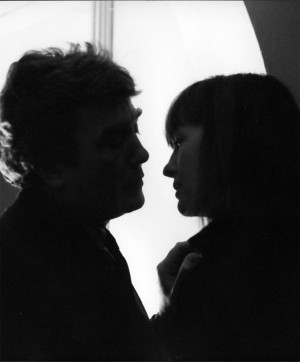

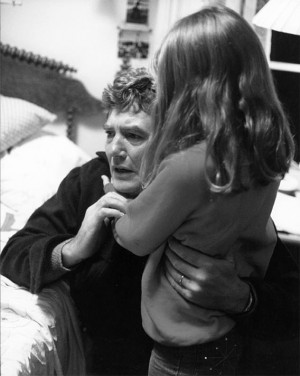

Albert Finney as George Dunlap, at the very beginning of the movie.

I had this notion of starting a film with a man walking down a staircase, walking into his study, sitting down at his desk and suddenly, putting his head in his hands, he sobs uncontrollably. It’s a scene that should be at the end of a movie, or at the very least at the end of the second act, but here it’s the first thing you experience on film. Sensible or not it was also the first thing we shot; putting us all on our toes from the very start. Diane and Albert both had very different approaches to their work — both exemplary — Diane, the consummate movie actress and Albert the lion of the London stage. Diane was extraordinary generous to the other actors in a scene, particularly off camera, when a lot of actors go back to their trailer — mentally if not physically. She was also extremely patient with the kids which wasn’t always easy for her as she didn’t have kids of her own at the time and was very wary of these four, often unpredictable, little monsters. She had come immediately from her previous film Reds where director Warren Beatty would regularly shoot upwards of 70 takes as a deliberate gambit to unsettle the actors; to take away the artifice and try and capture something special. That’s the theory anyway. Personally I don’t think actors get any better after 10 takes, and once you get into double figures many actors start to panic. At such a moment I always move the camera an inch to the left and change the slate number so it reads Take 1 again. It’s the same shot, but for the actor it’s a sign of progress and helps their confidence. Previously to this film I had mostly worked with unknowns, often having to put every eyebrow movement and sigh into the performance. This time I had these exceptional actors in front of me and it was a bit daunting, particularly with the imperious Albert. After all, who was I to criticize an actor who had won a Tony and nominated for an Oscar before I’d even passed an ‘O’ level? Diane has a built-in bullshit detector which makes it impossible for her to do a phony performance and she would add to, and subtlely change, her performance each take. Albert, with his theatrical background, would rehearse until he was happy with his performance and then repeat it. For a while I think that Albert was walking through the scenes. After all, if you’re used to doing a four hour performance on stage of the complete extended text of Marlowe’s Tamburlaine, a few Bo Goldman lines aren’t over taxing. However I think Diane’s excellent performances inspired him to raise his game. On one occasion Albert was sitting in the corner of the kitchen in an extremely pensive mood, in between takes of a particularly dramatic scene. I asked him what he was thinking? “She’s very good isn’t she?” he said. I think he was rather taken aback by Diane’s acting chops. “More than good.” I replied. I have to say that my relationship with Albert was workmanlike rather than “lovey”, in the British theatrical sense. Not that it started out that way. Albert said to me, “Why do you always say “Fantastic” after her [Diane’s] takes, and only “Good, Albert” after mine?” How intense and how personal actors make their work is a matter of opinion and technique. Some appear blasé and uninvolved and yet can deliver the most devastating performance. (“If you can’t feel it, fake it,” is the maxim.) In the theater someone once said, “Acting is keeping people from coughing for two hours.” Other actors aren’t happy until they give themselves a nervous breakdown. Albert’s famous quote is: “There are times when you think acting is a silly thing for a grown-up man to be doing.”  My difficulties with Albert came to the boil one night in an argument outside the Fairmont Hotel, half way through filming. I had spent most of the night strapped to the hood of a car with the camera, in the rain, as Albert and Diane drove to the hotel for the awards ceremony scene in the film. I made the mistake of rudely criticizing Albert in front of a gaggle of extras assembled in the hotel forecourt, and I paid the price. As I walked back to the camera, through the rain machines, I heard his footsteps splashing through the puddles behind me. Suddenly jocular Albert, everybody’s pal, turned into Othello or King Lear, front of stage at the Lyttleton, bellowing at me for insulting him. It was a very scary sight. I gulped, coughed, and apologized as the rain machines drenched us both. I heard this voice again many years later in The Dresser when Albert’s “Sir” Donald Wolfit character bellows as a train he had missed pulls out of the station, “STOP!” I shuddered when I heard it. After this, Albert and I had what can only be called a professional relationship. He stopped telling his John Guilgud and Larry Olivier stories in between takes and went about his work with estimable professionalism but minmal humour. It wasn’t a bundle of laughs anymore, but we ploughed onwards and, indeed, Diane and Albert did some of their best work. Albert is a tough, proud man who ploughs his own furrow, but, consumate actor that he is, always ready to reveal a vulnerable and fragile side too.

My difficulties with Albert came to the boil one night in an argument outside the Fairmont Hotel, half way through filming. I had spent most of the night strapped to the hood of a car with the camera, in the rain, as Albert and Diane drove to the hotel for the awards ceremony scene in the film. I made the mistake of rudely criticizing Albert in front of a gaggle of extras assembled in the hotel forecourt, and I paid the price. As I walked back to the camera, through the rain machines, I heard his footsteps splashing through the puddles behind me. Suddenly jocular Albert, everybody’s pal, turned into Othello or King Lear, front of stage at the Lyttleton, bellowing at me for insulting him. It was a very scary sight. I gulped, coughed, and apologized as the rain machines drenched us both. I heard this voice again many years later in The Dresser when Albert’s “Sir” Donald Wolfit character bellows as a train he had missed pulls out of the station, “STOP!” I shuddered when I heard it. After this, Albert and I had what can only be called a professional relationship. He stopped telling his John Guilgud and Larry Olivier stories in between takes and went about his work with estimable professionalism but minmal humour. It wasn’t a bundle of laughs anymore, but we ploughed onwards and, indeed, Diane and Albert did some of their best work. Albert is a tough, proud man who ploughs his own furrow, but, consumate actor that he is, always ready to reveal a vulnerable and fragile side too.

Filming was completed April 9th, 1981. After 62 shooting days we returned to London with 300, 000 feet of film. I didn’t want a conventional score for Shoot the Moon, probably as a reaction to Fame which was wall-to-wall music. Bo chose “Don’t Blame Me” from a catalog of MGM owned songs and I had it played on a piano with one finger — like a child would play it and I liked its simplicity. Also, through the film, I had played Rolling Stones, Bob Seeger and the Eagles —selfishly chosen because they were contemporary songs that meant a lot to me personally.

Afterwards

Shoot the Moon was the most personal film I ever made and a cathartic experience for me. Curiously, in the main, it was a very enjoyable film to make — considering all the pain up on the screen. Mostly, I suppose, because of being in such a beautiful and controlled environment, in the hills of Northern California. Albert and Diane continued their brilliant careers going on to win three more Oscar nominations apiece and Bo added to his own tally with one for Scent of a Woman. Sadly, Dana Hill died of a stroke in 1996, after many years of suffering from diabetes. Tracey Gold went on to success on TV (Growing Pains) and to a certain notoriety in the American fan-press for her anorexia. Tina Yothers also went on to fame on TV (Family Ties) and Peter Weller, of course, went on to be Robocop. I finished editing Shoot the Moon and immediately went on to Pink Floyd The Wall. Both films were invited to the Cannes Film Festival. Originally Shoot the Moon had been selected for the official competition, but when they viewed Pink Floyd The Wall, they wanted to swap them over and put Pink Floyd The Wall in competition instead. I said ‘no’ because Shoot the Moon needed the exposure more and so Pink Floyd The Wall got a ‘Gala’ late evening screening instead.  Working with Diane Keaton was a high point in the careers of myself, Bo Goldman, Michael Seresin, Alan Marshall and the rest of the crew. She was a superlative actress and refreshingly professional and unaffected at all times: a complete joy to work with. However, apparently, we didn’t have the same effect on her, as we didn’t even warrant a mention in her 2011 biography: our film just included in a list of her films that didn’t make much money. However many see Shoot the Moon as one of her finest performances, as the following reviews attest. I started out with a rule not to include reviews amongst these essays (probably more for self defence than immodesty) however I’ve added a few here because they were from critics who usually dumped on me from a great height. For instance: “A flawless movie from Alan Parker who previously made those execrable movies Fame, Midnight Express and Bugsy Malone” (Michael Sragow, Rolling Stone Magazine) And my favourite one of all was from the high priestess of critical defecation, the usually splenetic Pauline Kael, who wrote in the New Yorker: “There wasn’t a single scene in the English director, Alan Parker’s, first three feature films (Bugsy Malone, Midnight Express, Fame) that I thought rang true; there isn’t a scene in his new picture “Shoot the Moon”, that I think rings false. I’m a little afraid to say how good I think Shoot the Moon is…Alan Parker has given us a movie about separating that is perhaps the most revealing American movie of the era.” “One of the most powerful American movies of recent years. The picture seems like a miracle. Screenwriter Bo Goldman and Director Alan Parker have produced one of the rare movies that are central to our culture but not sentimental or square. The movie is a beautiful achievement.” (David Denby, New York Magazine)

Working with Diane Keaton was a high point in the careers of myself, Bo Goldman, Michael Seresin, Alan Marshall and the rest of the crew. She was a superlative actress and refreshingly professional and unaffected at all times: a complete joy to work with. However, apparently, we didn’t have the same effect on her, as we didn’t even warrant a mention in her 2011 biography: our film just included in a list of her films that didn’t make much money. However many see Shoot the Moon as one of her finest performances, as the following reviews attest. I started out with a rule not to include reviews amongst these essays (probably more for self defence than immodesty) however I’ve added a few here because they were from critics who usually dumped on me from a great height. For instance: “A flawless movie from Alan Parker who previously made those execrable movies Fame, Midnight Express and Bugsy Malone” (Michael Sragow, Rolling Stone Magazine) And my favourite one of all was from the high priestess of critical defecation, the usually splenetic Pauline Kael, who wrote in the New Yorker: “There wasn’t a single scene in the English director, Alan Parker’s, first three feature films (Bugsy Malone, Midnight Express, Fame) that I thought rang true; there isn’t a scene in his new picture “Shoot the Moon”, that I think rings false. I’m a little afraid to say how good I think Shoot the Moon is…Alan Parker has given us a movie about separating that is perhaps the most revealing American movie of the era.” “One of the most powerful American movies of recent years. The picture seems like a miracle. Screenwriter Bo Goldman and Director Alan Parker have produced one of the rare movies that are central to our culture but not sentimental or square. The movie is a beautiful achievement.” (David Denby, New York Magazine)  “Filled with fresh, acute and moving moments. Parker’s most controlled direction to date”. (David Ansen, Newsweek Magazine) “The movie mainlines pure feeling from its very first shot … Shoot the Moon sets so many emotional crosscurrents that the screen appears to tremble … Diane Keaton has never demonstrated as much depth as she does here … Albert Finny gives his finest performance on film. Alan Parker and Bo Goldman take such a fresh view of a marital break-up that it’s almost like watching this material on screen for the first time.” (Peter Rainer, Herald-Examiner) “A movie you won’t want to leave … A brilliant lacerating study of marriage on the rocks from two-fisted director Alan Parker and Oscar wining writer Bo Goldman … you can’t dismiss it and I’ll be willing to bet you’ll be haunted by the film long after it fades to black. For performances that drain you with their vitality, sincerity and power Albert Finney and Diane Keaton can’t be topped. For camera work that exhibits the highest artistry, and for writing as well as direction that transcends the confinements of a movie screen, Shoot the Moon is a towering achievement. It will leave you troubled, shocked and electrically charged like few other films in recent memory. It’s a wrenching but enriching experience that might well become a cinema classic.” (Rex Reed, Syndicated Film Critic) All anyone can say with certainty is that theirs (the Dunlap’s) is now among the most familiar of passages, and that Shoot the Moon is the best chart of it the movies have yet drawn.” Richard Schickel, Time Magazine “Diane Keaton and Albert Finney give the kind of performances that in the theatre become legendary.” (Pauline Kael, New Yorker) There’s a line in Fame I wrote for Montgomery (Paul McCrane) that goes: “No true artist should be afraid of what other people think of their work. A custard pie comes with the job.” (This line has stood me in good stead over the years, when I’ve been on the messy end of critical left hooks.) I think that most directors would agree that as much as we steel ourselves to criticism, it’s always preferable when someone says something nice. Sadly, for Shoot the Moon at least, another truism prevailed: good reviews meant little at the box office.

“Filled with fresh, acute and moving moments. Parker’s most controlled direction to date”. (David Ansen, Newsweek Magazine) “The movie mainlines pure feeling from its very first shot … Shoot the Moon sets so many emotional crosscurrents that the screen appears to tremble … Diane Keaton has never demonstrated as much depth as she does here … Albert Finny gives his finest performance on film. Alan Parker and Bo Goldman take such a fresh view of a marital break-up that it’s almost like watching this material on screen for the first time.” (Peter Rainer, Herald-Examiner) “A movie you won’t want to leave … A brilliant lacerating study of marriage on the rocks from two-fisted director Alan Parker and Oscar wining writer Bo Goldman … you can’t dismiss it and I’ll be willing to bet you’ll be haunted by the film long after it fades to black. For performances that drain you with their vitality, sincerity and power Albert Finney and Diane Keaton can’t be topped. For camera work that exhibits the highest artistry, and for writing as well as direction that transcends the confinements of a movie screen, Shoot the Moon is a towering achievement. It will leave you troubled, shocked and electrically charged like few other films in recent memory. It’s a wrenching but enriching experience that might well become a cinema classic.” (Rex Reed, Syndicated Film Critic) All anyone can say with certainty is that theirs (the Dunlap’s) is now among the most familiar of passages, and that Shoot the Moon is the best chart of it the movies have yet drawn.” Richard Schickel, Time Magazine “Diane Keaton and Albert Finney give the kind of performances that in the theatre become legendary.” (Pauline Kael, New Yorker) There’s a line in Fame I wrote for Montgomery (Paul McCrane) that goes: “No true artist should be afraid of what other people think of their work. A custard pie comes with the job.” (This line has stood me in good stead over the years, when I’ve been on the messy end of critical left hooks.) I think that most directors would agree that as much as we steel ourselves to criticism, it’s always preferable when someone says something nice. Sadly, for Shoot the Moon at least, another truism prevailed: good reviews meant little at the box office.

All text © Alan Parker. All photos © MGM. Stills photography: Elliot Marks. Cinematographer: Michael Seresin.