COME SEE THE PARADISE

The making of the film by Alan Parker

For many years I have had a haunting picture by the great photographer, Dorothea Lange pinned to my wall. The picture shows an elderly Japanese man sitting with his two grandchildren in San Francisco, 1941, awaiting deportation and internment. The old man’s dignity and self-respect stare straight out at you from the photograph, as does the bemused ingenuousness of his two grandsons. As with all great photographs, you long to know the story behind the faces. In September of 1988 I was finishing Mississippi Burning in Los Angeles and thinking of writing a love story that had so far eluded me in my work. I had a folder full of scribbled notes on a story about a politically left-wing character in the States in the 1930’s. Robert Colesberry, my producer on Mississippi Burning , was one day talking to me about the photograph on my wall and about the possibility of doing a film on the internment of Japanese Americans, when the threads for our story came together. Once I had finished with Mississippi Burning, I locked myself away with the research materials — over fifty books and a pile of video tapes, newspaper and magazine articles – and began work. At the end of two months I had two thick folders full of notes and then began the first draft which was completed by the end of January ’89. We were fortunate enough to find an enthusiastic reception to the script from Roger Birnbaum at Twentieth Century Fox, a studio I had not worked with before. At a party at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art I saw Barry Diller, the then Chairman of Fox, who said that my script hade made him cry. Anyone who knows Barry would suspect that this is an ocular impossibility, but his enthusiasm for the script was much appreciated. The name of the character in my story is Jack McGurn, an Irish American and probably, subconsciously, I named him Jack because deep down I saw Jack Nicholson. Unfortunately the Jack in my story is a much younger man than Nicholson, and so I had to think again. For me, Dennis Quaid was as close to the character Jack that I’d written, as any of the younger American actors. He too is of Irish descent and he has an openness and feisty ingenuous honesty that I wanted in the character. I met with Dennis, who had read my first draft, and he reminded me that I had done a screen test with him for Midnight Expres twelve years earlier. He was my first choice for Come See the Paradis and so I felt very encouraged.

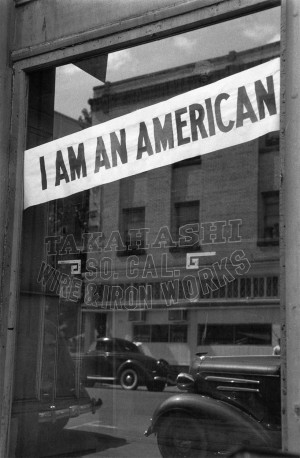

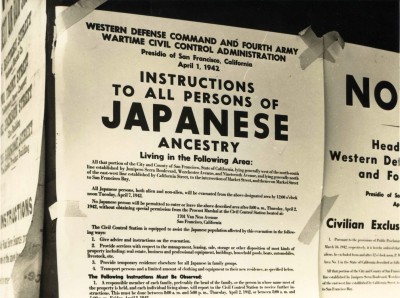

For many years I have had a haunting picture by the great photographer, Dorothea Lange pinned to my wall. The picture shows an elderly Japanese man sitting with his two grandchildren in San Francisco, 1941, awaiting deportation and internment. The old man’s dignity and self-respect stare straight out at you from the photograph, as does the bemused ingenuousness of his two grandsons. As with all great photographs, you long to know the story behind the faces. In September of 1988 I was finishing Mississippi Burning in Los Angeles and thinking of writing a love story that had so far eluded me in my work. I had a folder full of scribbled notes on a story about a politically left-wing character in the States in the 1930’s. Robert Colesberry, my producer on Mississippi Burning , was one day talking to me about the photograph on my wall and about the possibility of doing a film on the internment of Japanese Americans, when the threads for our story came together. Once I had finished with Mississippi Burning, I locked myself away with the research materials — over fifty books and a pile of video tapes, newspaper and magazine articles – and began work. At the end of two months I had two thick folders full of notes and then began the first draft which was completed by the end of January ’89. We were fortunate enough to find an enthusiastic reception to the script from Roger Birnbaum at Twentieth Century Fox, a studio I had not worked with before. At a party at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art I saw Barry Diller, the then Chairman of Fox, who said that my script hade made him cry. Anyone who knows Barry would suspect that this is an ocular impossibility, but his enthusiasm for the script was much appreciated. The name of the character in my story is Jack McGurn, an Irish American and probably, subconsciously, I named him Jack because deep down I saw Jack Nicholson. Unfortunately the Jack in my story is a much younger man than Nicholson, and so I had to think again. For me, Dennis Quaid was as close to the character Jack that I’d written, as any of the younger American actors. He too is of Irish descent and he has an openness and feisty ingenuous honesty that I wanted in the character. I met with Dennis, who had read my first draft, and he reminded me that I had done a screen test with him for Midnight Expres twelve years earlier. He was my first choice for Come See the Paradis and so I felt very encouraged.  At the heart of our story however is the Japanese American family, and I begun the casting process which was to last six months and took us on “open calls” to wherever we could identify large Asian American populations: San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, New York, Los Angeles and Hawaii. We also cast the net as far as Tokyo. In all, we read with over two thousand possibilities, but eventually found our main cast in Los Angeles and New York. The Kawamura family obviously had to be as authentic as possible – had to speak Japanese, and the American-born children needed to be fluent in English. Lily Kawamura, our main character, was the most difficult to find and I had narrowed it down to three actresses whom I tested with Dennis before settling on Tamlyn Tomita. Tamlyn had her own special beauty and an inner calm and dignity which was very impressive. She had the advantage of understanding the character totally at a personal level, being both Nisei (Second generation, American-born) and Sansei (Third generation), her mother being Japanese-born (Issei) and her father Nisei. I had seem Sab Shimono, who plays Mr. Kawamura, and Stan Egi (who plays the disillusioned Charlie), in Philip Gotanda’s wonderful off-Broadway play about the perception of Japanese American stereotypes, “Yankee Dawg, You Die”. I met them backstage afterwards and said that I hoped that they were both free in August. Shizuko Hoshi, who plays Mrs. Kawamura, I had met and read with in Los Angeles. She is a very experienced theatre actress and director in her own right, having done many works with her husband Mako at the East West Players Theatre Group. She too was very close to her character, being Japanese born, but had lived in the United States for thirty years. Akemi Nishino, who plays Dulcie, I had seen in a restaurant in Los Angeles and asked her to come in to read for me the next day. Her good humor and honest naturalism livened up every scene she was in. Ron Yamamoto, who plays Harry, I met in New York. He had given up a career in law to become an actor, and his gentle qualities and optimism seemed close to those of Harry who suffers the indignation of internment and rejection, but never loses faith in the ‘American Dream’. Naomi Nakano and Brady Tsurutani, who play the younger Kawamuras, Joyce and Frankie, were both from Los Angeles. In April of 1989, I began looking for locations which took us to Portland, Seattle, and San Francisco. In Portland we were drawn to a downtown area which was once the old ‘J’ town, or Japantown, and which is now a curious mixture of New York’s Bowery and Chinatown. I had completed my second draft of the screenplay, written in a hotel room in Portland, in between walking the streets looking for possible locations. The story, it was clear, could be pulled in many directions, but everything kept tugging the script back to the heart of things – our Japanese American family and their internment, which realistically could only be the final Act in our story. A writer friend of mine referred me to Julius Caesar, the classic blueprint of dramatic construction, which has at its fulcrum, Brutus thrusting his dagger into Caesar. I thought this a very apt metaphor for the film industry if not terribly helpful to our story – my other area of “constructional” inspiration was Doctor Zhivago, where in the middle of the third act, Zhivago starts writing the ‘Lara’ poems, (not exactly Hollywood textbook). In Honolulu I had organized a mammoth “Open Call” casting session. Hawaii has the largest Japanese American population and therefore could not be overlooked in our search and I read with over seven hundred hopefuls. In the Mojave Desert near Palmdale, one hour from Los Angeles, our Locations people had found a possible site for our biggest production problem: the building of the internment camp. The actual camp at Manzanar in the remote northeast of California. which during internment was the biggest ‘city’ between Los Angeles and Reno. is once again a tract of barren, windswept desert marked with a simple plaque that reads: In the early part of World War II, 110,000 persons of Japanese Ancestry were interned in relocation centers by Executive Order No. 9066 issued on February 19. 1942. Manzanar, the first of ten such concentration camps, was bounded by barbed wire and guard towers, confining 10,000 persons, the majority being American citizens. May the injustices and humiliation suffered here as a result of hysteria, racism and economics exploitation never emerge again The marker and stone gatehouse are all that remain of the Manzanar camp.

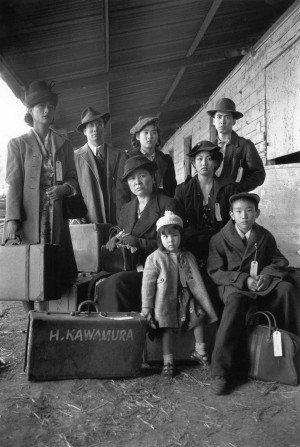

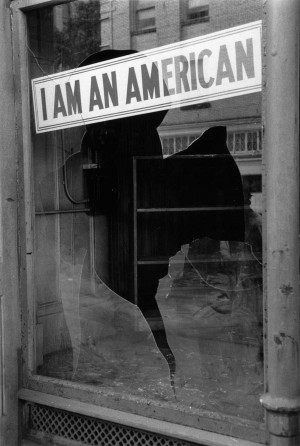

At the heart of our story however is the Japanese American family, and I begun the casting process which was to last six months and took us on “open calls” to wherever we could identify large Asian American populations: San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, New York, Los Angeles and Hawaii. We also cast the net as far as Tokyo. In all, we read with over two thousand possibilities, but eventually found our main cast in Los Angeles and New York. The Kawamura family obviously had to be as authentic as possible – had to speak Japanese, and the American-born children needed to be fluent in English. Lily Kawamura, our main character, was the most difficult to find and I had narrowed it down to three actresses whom I tested with Dennis before settling on Tamlyn Tomita. Tamlyn had her own special beauty and an inner calm and dignity which was very impressive. She had the advantage of understanding the character totally at a personal level, being both Nisei (Second generation, American-born) and Sansei (Third generation), her mother being Japanese-born (Issei) and her father Nisei. I had seem Sab Shimono, who plays Mr. Kawamura, and Stan Egi (who plays the disillusioned Charlie), in Philip Gotanda’s wonderful off-Broadway play about the perception of Japanese American stereotypes, “Yankee Dawg, You Die”. I met them backstage afterwards and said that I hoped that they were both free in August. Shizuko Hoshi, who plays Mrs. Kawamura, I had met and read with in Los Angeles. She is a very experienced theatre actress and director in her own right, having done many works with her husband Mako at the East West Players Theatre Group. She too was very close to her character, being Japanese born, but had lived in the United States for thirty years. Akemi Nishino, who plays Dulcie, I had seen in a restaurant in Los Angeles and asked her to come in to read for me the next day. Her good humor and honest naturalism livened up every scene she was in. Ron Yamamoto, who plays Harry, I met in New York. He had given up a career in law to become an actor, and his gentle qualities and optimism seemed close to those of Harry who suffers the indignation of internment and rejection, but never loses faith in the ‘American Dream’. Naomi Nakano and Brady Tsurutani, who play the younger Kawamuras, Joyce and Frankie, were both from Los Angeles. In April of 1989, I began looking for locations which took us to Portland, Seattle, and San Francisco. In Portland we were drawn to a downtown area which was once the old ‘J’ town, or Japantown, and which is now a curious mixture of New York’s Bowery and Chinatown. I had completed my second draft of the screenplay, written in a hotel room in Portland, in between walking the streets looking for possible locations. The story, it was clear, could be pulled in many directions, but everything kept tugging the script back to the heart of things – our Japanese American family and their internment, which realistically could only be the final Act in our story. A writer friend of mine referred me to Julius Caesar, the classic blueprint of dramatic construction, which has at its fulcrum, Brutus thrusting his dagger into Caesar. I thought this a very apt metaphor for the film industry if not terribly helpful to our story – my other area of “constructional” inspiration was Doctor Zhivago, where in the middle of the third act, Zhivago starts writing the ‘Lara’ poems, (not exactly Hollywood textbook). In Honolulu I had organized a mammoth “Open Call” casting session. Hawaii has the largest Japanese American population and therefore could not be overlooked in our search and I read with over seven hundred hopefuls. In the Mojave Desert near Palmdale, one hour from Los Angeles, our Locations people had found a possible site for our biggest production problem: the building of the internment camp. The actual camp at Manzanar in the remote northeast of California. which during internment was the biggest ‘city’ between Los Angeles and Reno. is once again a tract of barren, windswept desert marked with a simple plaque that reads: In the early part of World War II, 110,000 persons of Japanese Ancestry were interned in relocation centers by Executive Order No. 9066 issued on February 19. 1942. Manzanar, the first of ten such concentration camps, was bounded by barbed wire and guard towers, confining 10,000 persons, the majority being American citizens. May the injustices and humiliation suffered here as a result of hysteria, racism and economics exploitation never emerge again The marker and stone gatehouse are all that remain of the Manzanar camp. Our own camp obviously could not cover the square mile of the original 864 buildings, but it was certainly going to be an enormous undertaking. Our own location, within striking distance of Los Angeles, had terrain similar to the original camp. The land however turned out to be owned by no less than 55 different owners in different parts of the world as scattered as Paris, Toronto, Honolulu, Montana and New Jersey. All had to be cleared for permission. (We tracked down one owner in Paris who had brought the land in 1974. We found that he had driven off a cliff in Morocco the previous year and when we finally made contact with his family for permission, they were surprised and happy to know that they actually owned land in California.) Eventually we cleared 35 acres of land to build our camp. In Seattle and Tacoma, we found a number of locations to compliment those in Portland. I met with my Director of Photography, Michael Seresin and we walked through the many scenes in the actual locations. We had accumulated over one thousand photographs of the period and we flicked through each one as we tried to visualize our film. In Portland our street had an army of construction people busy at work as they transformed it into a giant movie set to replicate the original Little Tokyo. Every single storefront had to be worked on, rebuilt, dressed and repainted. We also walked around the many possible locations for the Kawamura house, seemingly the easiest , but ultimately the most difficult to find. We have evolved a way of ‘location’ filming that means finding the actual place but completely ripping out everything to build what we have envisaged. It always seems to me a humorous, if not perverse, exercise as we walk through people’s living rooms, nodding hellos to the occupants as we discuss tearing out their modern fireplaces and demolishing their kitchens. In fact, we were an entire film studio on location with construction workshops, prop house, makeup and hair, art department, costume department, transportation, lights, camera department, special effects, etc – a mobile movie studio that will trundle in to seven cities and ninety locations, demolish, rebuild, redress and put them back to exactly how we found them.(Well almost as we found them.) For our opening sequence I had been listening to the agricultural complexities of planting the flowers that I’d asked for and the time it would take. The Willamette Valley, “the most fertile land in America”, they had told me — except for the flowers I’d chosen, it seemed. “How high would they be when we arrive to shoot? What color exactly?” There were too many shrugs from the farmers for me to be entirely confident. Also, we had to plant and instigate our strawberry fields for our closing Florin scenes. I finally settled on fast-growing beans. Those, they assured me, would grow in no time. Wearing two hats as writer and director is never easy and on the scripts I’ve not written myself, I’m usually ready to kill the writer at this stage on a film, and even if I’ve written it myself, the feeling is much the same. Films aren’t words on a page, a screenplay is merely a working manual, it has to be organic. Many aspects, attitudes, textures, and details are borne of the filmmaking process that, although you can never escape, the heart of an original idea, a film takes on a life of its own, taking you on its own journey. It was clear that our desires to match the sheer size of the original internment camp would be very difficult with our limited resources. In 1942 when they built Manzanar it cost $3,507,018. At today’s prices, that would mean $55 million to replicate it exactly, a little more than we could afford, and so every shot had to be accurately conceived before we began constructing a single building. Clearly, in movie terms, history is expensive. Going through the racks of clothes shirt by shirt, hat by hat, it became obvious that we had a long way to go. On our biggest days we had to dress, in accurate period costume, over 600 actors and, probably because there are so few period films now made in the United States, the stocks are depleted and so we had to look further afield. In my meetings with various Japanese American organizations, many had expressed concerns that all things would be accurate and I had promised them they would be — for my sake as well as theirs. We had formed a panel of twenty or so Nisei Japanese Americans who had lived through the times, to give us their opinions as to the accuracy of each department’s endeavours — but often, no one could ever agree on this cup, or those chopsticks and so we tended to go with the consensus. We had built a scale model of the internment camp in order to pin down the shots I needed. Bob Colesberry followed me around, with his obligatory producer’s long face, as he added up the actual fiscal consequences of another two inch hut added to the board. We knew that we had to perform miracles to pull off a film that would normally cost twice our budget.

Our own camp obviously could not cover the square mile of the original 864 buildings, but it was certainly going to be an enormous undertaking. Our own location, within striking distance of Los Angeles, had terrain similar to the original camp. The land however turned out to be owned by no less than 55 different owners in different parts of the world as scattered as Paris, Toronto, Honolulu, Montana and New Jersey. All had to be cleared for permission. (We tracked down one owner in Paris who had brought the land in 1974. We found that he had driven off a cliff in Morocco the previous year and when we finally made contact with his family for permission, they were surprised and happy to know that they actually owned land in California.) Eventually we cleared 35 acres of land to build our camp. In Seattle and Tacoma, we found a number of locations to compliment those in Portland. I met with my Director of Photography, Michael Seresin and we walked through the many scenes in the actual locations. We had accumulated over one thousand photographs of the period and we flicked through each one as we tried to visualize our film. In Portland our street had an army of construction people busy at work as they transformed it into a giant movie set to replicate the original Little Tokyo. Every single storefront had to be worked on, rebuilt, dressed and repainted. We also walked around the many possible locations for the Kawamura house, seemingly the easiest , but ultimately the most difficult to find. We have evolved a way of ‘location’ filming that means finding the actual place but completely ripping out everything to build what we have envisaged. It always seems to me a humorous, if not perverse, exercise as we walk through people’s living rooms, nodding hellos to the occupants as we discuss tearing out their modern fireplaces and demolishing their kitchens. In fact, we were an entire film studio on location with construction workshops, prop house, makeup and hair, art department, costume department, transportation, lights, camera department, special effects, etc – a mobile movie studio that will trundle in to seven cities and ninety locations, demolish, rebuild, redress and put them back to exactly how we found them.(Well almost as we found them.) For our opening sequence I had been listening to the agricultural complexities of planting the flowers that I’d asked for and the time it would take. The Willamette Valley, “the most fertile land in America”, they had told me — except for the flowers I’d chosen, it seemed. “How high would they be when we arrive to shoot? What color exactly?” There were too many shrugs from the farmers for me to be entirely confident. Also, we had to plant and instigate our strawberry fields for our closing Florin scenes. I finally settled on fast-growing beans. Those, they assured me, would grow in no time. Wearing two hats as writer and director is never easy and on the scripts I’ve not written myself, I’m usually ready to kill the writer at this stage on a film, and even if I’ve written it myself, the feeling is much the same. Films aren’t words on a page, a screenplay is merely a working manual, it has to be organic. Many aspects, attitudes, textures, and details are borne of the filmmaking process that, although you can never escape, the heart of an original idea, a film takes on a life of its own, taking you on its own journey. It was clear that our desires to match the sheer size of the original internment camp would be very difficult with our limited resources. In 1942 when they built Manzanar it cost $3,507,018. At today’s prices, that would mean $55 million to replicate it exactly, a little more than we could afford, and so every shot had to be accurately conceived before we began constructing a single building. Clearly, in movie terms, history is expensive. Going through the racks of clothes shirt by shirt, hat by hat, it became obvious that we had a long way to go. On our biggest days we had to dress, in accurate period costume, over 600 actors and, probably because there are so few period films now made in the United States, the stocks are depleted and so we had to look further afield. In my meetings with various Japanese American organizations, many had expressed concerns that all things would be accurate and I had promised them they would be — for my sake as well as theirs. We had formed a panel of twenty or so Nisei Japanese Americans who had lived through the times, to give us their opinions as to the accuracy of each department’s endeavours — but often, no one could ever agree on this cup, or those chopsticks and so we tended to go with the consensus. We had built a scale model of the internment camp in order to pin down the shots I needed. Bob Colesberry followed me around, with his obligatory producer’s long face, as he added up the actual fiscal consequences of another two inch hut added to the board. We knew that we had to perform miracles to pull off a film that would normally cost twice our budget.

The Kawamuras: Akemi Nishino, Ron Yamamoto, Naomi Nakano, Stan Egi, Shizuko Hoshi, Tamlyn Tomita, Elizabeth Gilliam, Brady Tsurutani, Portland, Oregon

In the costume department each one of our large cast had to be fitted and I sat for hours as Molly Maginnis dressed each actor in a dozen different options – every period hat, shirt, tie, sock, suit, blouse, purse, skirt, bra and pair of suspenders. We had assembled miles of racks of period clothes and boxes of accessories so that our options seemed endless. I had papered the walls with photo-copies of the hundreds of photographs we had accumulated and, whenever in doubt, the correct sartorial choice was always staring out at us. In August I began a week of rehearsals with the Kawamuras. This was the first time that the whole family has been able to get together and we began to read through the script. Apart from seeing how each of the family members interacted with one another, this time was also a moment of truth for the script. Many of our scenes had multi-layered dialogue with eight characters – and two languages. Our time was spent in ironing out whatever problems the script presented and, probably more importantly, allowing the family to become a comfortable, cohesive group. In our cast Shizuko Hoshi (Mrs. Kawamura) and Akemi Nishino (Dulcie) were fluent in Japanese, being Japanese born. Naomi Nakano (Joyce) and Tamlyn Tomita (Lily) both had Japanese mothers and so they too were proficient. Sab Shimono (Mr. Kawamura), who was the only one who had experienced the camps as a young boy, spoke the Japanese of a Nisei, and worked hard with a coach to polish his accent. Stan Egi (Charlie), Ron Yamamoto (Harry) and Brady Tsurutani (Frankie) like many Sansei Japanese Americans had spoken very little Japanese at home. (After the war, and partly due to the humiliation of the camps, many Japanese families rarely spoke Japanese.) I returned to Los Angeles to pre-record the 30’s songs that we needed in the film. Sanae Hosaka, who sings the Japanese song “Wasurecha Iya Yo” in the social club, was a Portland housewife who I coaxed in to singing at her audition. We also had to record Ron Yamamoto singing “Until the Real Thing Comes Along” and our three Japanese “Andrews Sisters” singing “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree”. These tracks had to be layed down in advance, as each of the singers would be singing to playback, albeit to their own voices. Watching their animated Japanese faces singing such American songs seemed to me to epitomize the younger Nisei, desperate to be accepted as Americans whilst being locked in a camp that said they weren’t. Whilst casting the smaller parts in Portland I read with a girl called Cynthia Sao for a small part. At the end of the reading she dug into her bag and brought out a framed photograph to show me. It was the Dorothea Lange photograph of the old man and his two grandsons in San Francisco – the same photograph that I had pinned on my wall before writing a word and copies of which I had pinned on every wall of everyone’s office on the film. I even had a copy scotch-taped to my bathroom mirror in my hotel, to remind me of who I was making this film about. “This is a photograph of my father, uncle and great-grandfather,” she said shyly. I couldn’t believe it. I grabbed hold of her, kissed her, and dragged her blushing and bewildered into Bob Colesberry’s office to show him her picture. I asked to meet her father, Gerry Aso, the small boy in the famous photograph, and Colesberry and I met him for lunch. Gerry, now a Portland dentist, was photographed with his brother Bill in 1942 in San Francisco before deportation to the camps at Topaz and Amache. Their grandfather had run a successful laundry business before internment, which accounts for his immaculately pressed overcoat and crisp white collar he wears in the photograph.

Caroline Junko King (Mini) and Tamlyn Tomita (Lily Kawamura/McGann, Albany, Oregon

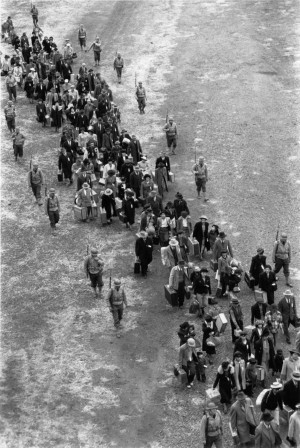

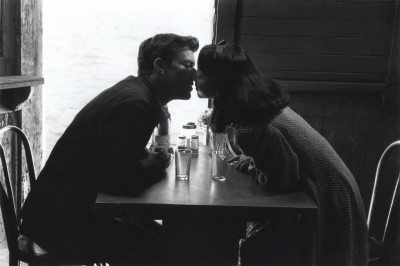

We began shooting on August 19, 1989 in flower fields in the Oregon countryside. We had ploughed our road through the flowers (which had miraculously grown as the farmers had said they would, three months previously) and at 5 a.m. we were ready to shoot as the early morning light skimmed across the fields. At the Kawamura House, the dynamics of the scenes played well, owing much to our rehearsals. With its double layers of language we see both a Japanese family and an American family, at once it’s the essence of the world we were trying to capture. Our racetrack at Portland Meadows was to approximate similar “assembly centers” at Santa Anita Racetrack outside Los Angeles and Tanforan Racetrack in San Francisco to which Japanese Americans were temporarily evacuated in May of ‘42 before the actual internment (“relocation”) camps could be constructed. It was a long day which our extras suffered bravely, many who had arrived in the early hours to be prepared for costume, makeup and hair. Our Little Tokyo street was, up to then, our biggest set; everything had been worked on by our art department in order for me to film down the full length of the street. Our sign painters, including two elderly Japanese calligraphers, had replaced over one hundred different signs and hopefully we got close to life in Little Tokyo in 1936. We also assembled over 300 vehicles to use in these scenes as we filmed Jack and Charlie running along the street and Jack’s first sight of Lily working in Mr. Matsui’s costume shop. We also shot the scenes of the violence that followed in the wave of hysteria after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The most difficult intimate scenes were shot in the Matsui Costume Shop as Jack and Lily reunite after his arrest. It’s one complete shot as the camera slowly moves towards the two lovers, lying on a bed of costumes in the back room.

They can break both my arms and legs and it could never hurt me as much as losing you, Lily. You have a happiness inside you that makes you so beautiful, as if you has a little bag of magic that only you could dip into…

Jack

Each day of filming called for many different scenes as we travelled across the city. Moving in the middle of the day is never very satisfying logistically or creatively, but such were the exigencies of our gruelling schedule. Moving is also no easy operation, as, lined up outside of every location, were the twenty-five trucks of this mobile film studio of 110 people. Elizabeth Gilliam, who plays the little Mini, was a beautifully serene four-year-old whose passive exterior disguised a renegade spirit. This manifested itself in her alert, darting eyes which mostly found their way into the camera lens, negating the shots, and shredding our nerves. Out in the Oregon countryside the beans we had planted many weeks before had grown steadily and the shots were exactly as I had envisaged them, as the family in their new home sit in silence after the news of dropping of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima, August 6th , 1945. We also continued the Florin scenes as Lily recounts her story to Mini (Caroline Junko King). We had rehearsed all of their scenes together back in Portland before we began shooting and the actors were very comfortable with one another. We had scouted dozens of country railway stations without success, and so I decided to build our own. I had seen an old derelict building on one of our location scouts and we bought it whole and transported every plank and gutter pipe to this rural spur on the railroad. During our location hunt we had built the platform and planted the surrounding greenery to knit the station into its new home. The old McCoy store where Lily relates the conclusion of the story was also semi-derelict but complimented the station platform that now sat outside – as it might have done for eighty years. The period steam train, from which Jack appears in 1948, was brought down from Portland, necessitating the removal of 500 empty boxcars awaiting the summer harvest, which were parked in the way along the hundred miles of rusty railway.

Akemi Nishino (Dulcie Kawamura), Brady Tsurutani (Frankie Kawamura) smash their father’s precious record collection prior to deportation.

Back in Portland at the Kawamura house, we shot the scenes of Jack as he is goaded into singing the song he’d learned by heart in the Japanese movie theatre – thereby gaining a clumsy acceptance into the family. We also shot one of my favourite scenes in the film of the family breaking Mr. Kawamura’s precious record collection – too heavy to take with them to the camp and to precious to leave behind. Jumping back and forth in the story continuity, we found ourselves in the union offices of the ‘New York Projectionists Union’. I had grabbed this particular thread of our story from a newspaper article in a 1942 Brooklyn newspaper which mentioned the 1936 bombing of a non-union movie theatre and the subsequent arrest of the arsonist during the war. This became the background of Dennis’ character Jack McGurn. Pruitt Vince, who plays Augie, I had first met in New Orleans on “Angel Heart” and he had also played one of the conspirators in Mississippi Burnin . Curiously, I rarely work with the same actors twice, probably out of my lack of imagination as well as patience. I tend to always think of actors who I have worked with as locked into the character they first played with me, and casting them in other roles always seems to me to be a betrayal of the original characters. Pruitt, however, defied this premise, and his odd, flickering eyes, bouncing around like brown ping-pong balls in a lottery barrel, once again gave the focus puller a headache. Our biggest day’s filming was at the Portland railway station with 500 extras dressed and propped – and a giant engine with eight carriages that had taken two weeks travel from Vancouver, Canada. We were filming at Portland’s main — and very busy — railway station and every so often we had to stop filming as a modern train thundered in. We wondered what the passengers must have thought, stepping off the modern commuter trains into our weird time warp, suddenly jostling through the crowds of 1942 evacuees dressed in period costume. The intimate goodbye scene were especially difficult as they were against a backdrop of five hundred extras, all with their own specific instructions and camera hogging agendas. At the end of the day I decided to see what all of this mass of refugees looked like from above on the iron railroad bridge that spanned the railway yards. Seen from so high up, our five hundred extras seemed like a couple of dozen, but when I asked them to move, it made a powerful and evocative image.  The Moreland Theater in Portland was a beautiful, protected building, and the owners stood nervously and incredulously behind us as I described to the special effects people about how I wanted to burn it down. It was obviously going to be impossible to cause a real fire without damage, and so the scene was divided in two: the larger fire being built on an outdoor set. After burning down three Churches and a farm on “Mississippi Burning”, the Moreland Theater presented few problems to my crew. I had chosen the Ronald Coleman – Claudette Colbert film “Under Two Flags” for no particular reason other than it was, correctly, a 1936 film and more importantly, Fox owned it, so we could use it for free. We had found the interior of the Kawamura Movie Theatre pretty well as it’s shown. A little seedy and run down, ‘The Clinton’, as it was called, had changed little in fifty years. It was the sort of place that played The Rocky Horror Show and Pink Floyd The Wal at midnight screenings. We had been researching old black and white Japanese movies for months and finding one intact, to which the rights could be cleared, was a contractual quagmire. We finally turned up “Oshidori Utagassen”, whose quaint charm seemed to fit the bill. Our schedule called for three moves each day as the mobile film army criss-crossed Portland as we vainly tried to keep up with our impossible schedule. We filmed at the Matsui Costume Shop in the morning, then moved to the ‘Bus Station’: in fact, a brick shell of an old garage filled with giant Greyhound busses where we filmed Lily and Mini returning to Los Angeles. Little Elizabeth Gilliam’s darting eyes still kept flickering towards camera at crucial moments. I eventually sat on top of a ladder waving a bedraggled doll to distract her attention from our camera lens. On our third move in one day, we were in a small schoolhall where Lily takes Mini out of school prior to the evacuation. The whole crew helped dress the children’s paintings on the wall to help a hard pressed art department. It reminded me of the stories of the old days of filming in England, when the camera would be panning across a wall carefully keeping slightly behind the painter who was still painting it. At the end of September the entire company moved to the town of Astoria on the Oregon coast where we filmed the Terminal Island scenes. Our main difficultly was forever chasing the light — each scene having had a particular light quality allocated to it. This complicated an already conjested schedule as we forever juggled the possibilities. The scene with Lily and Jack kissing in the mud was done at five in the morning as the light peeped over the horizon and skipped across the mud. By six a.m. the good light was gone. We had created the whole of Terminal Island harbor, as the Kawamura children sought news of their father. We had amassed thirty period fishing boats for the scene, and my New York propmen earned their sea legs as they fought the tide and the leaking hulls to get the boats into position for each shot. The company then moved further north to Cathlamet, a fishing town on the Washington coast. On the side of the old cannery building was a plaque celebrating the Chinese workers who once worked in the cannery before the fishing industry collapsed, like so many on the west coast, due to over-fishing. The building was completely empty when we found it — we brought in the the whole working cannery with its steam, water, fish gutters, ice breakers, conveyor belts, etc. is an illusion to create the period atmosphere. Into the cannery shell we had transported machinery from all over Oregon. The main machine that Jack works beside was a monstrous fish-gutting contraption once called ‘The Iron Chink’, which at the turn of the century had replaced two hundred dextrous Chinese cannery workers. At the end of two days we had filmed our cannery labor dispute and disposed of over 1000 pounds of fish. During the first takes, the razor sharp spine of one of the thrown fish impaled itself into the leg of a stuntman who was taken to hospital. We stopped filming for an hour while the prop department de-spined the seemingly harmless missiles. I never imagined when I wrote the scene that pelting someone with a fish could be so dangerous. As I stood in the raised ‘office’ we had built inside the cannery, I looked down on the crew as they rearranged the props, machinery, lights, tracks, cameras. It seemed that the entire crew of 100 were working at the same time, many of them having been up since the early hours. Even the usually insular makeup department, in their rubber gloves, were helping out by tossing smelly fish from table to table.

The Moreland Theater in Portland was a beautiful, protected building, and the owners stood nervously and incredulously behind us as I described to the special effects people about how I wanted to burn it down. It was obviously going to be impossible to cause a real fire without damage, and so the scene was divided in two: the larger fire being built on an outdoor set. After burning down three Churches and a farm on “Mississippi Burning”, the Moreland Theater presented few problems to my crew. I had chosen the Ronald Coleman – Claudette Colbert film “Under Two Flags” for no particular reason other than it was, correctly, a 1936 film and more importantly, Fox owned it, so we could use it for free. We had found the interior of the Kawamura Movie Theatre pretty well as it’s shown. A little seedy and run down, ‘The Clinton’, as it was called, had changed little in fifty years. It was the sort of place that played The Rocky Horror Show and Pink Floyd The Wal at midnight screenings. We had been researching old black and white Japanese movies for months and finding one intact, to which the rights could be cleared, was a contractual quagmire. We finally turned up “Oshidori Utagassen”, whose quaint charm seemed to fit the bill. Our schedule called for three moves each day as the mobile film army criss-crossed Portland as we vainly tried to keep up with our impossible schedule. We filmed at the Matsui Costume Shop in the morning, then moved to the ‘Bus Station’: in fact, a brick shell of an old garage filled with giant Greyhound busses where we filmed Lily and Mini returning to Los Angeles. Little Elizabeth Gilliam’s darting eyes still kept flickering towards camera at crucial moments. I eventually sat on top of a ladder waving a bedraggled doll to distract her attention from our camera lens. On our third move in one day, we were in a small schoolhall where Lily takes Mini out of school prior to the evacuation. The whole crew helped dress the children’s paintings on the wall to help a hard pressed art department. It reminded me of the stories of the old days of filming in England, when the camera would be panning across a wall carefully keeping slightly behind the painter who was still painting it. At the end of September the entire company moved to the town of Astoria on the Oregon coast where we filmed the Terminal Island scenes. Our main difficultly was forever chasing the light — each scene having had a particular light quality allocated to it. This complicated an already conjested schedule as we forever juggled the possibilities. The scene with Lily and Jack kissing in the mud was done at five in the morning as the light peeped over the horizon and skipped across the mud. By six a.m. the good light was gone. We had created the whole of Terminal Island harbor, as the Kawamura children sought news of their father. We had amassed thirty period fishing boats for the scene, and my New York propmen earned their sea legs as they fought the tide and the leaking hulls to get the boats into position for each shot. The company then moved further north to Cathlamet, a fishing town on the Washington coast. On the side of the old cannery building was a plaque celebrating the Chinese workers who once worked in the cannery before the fishing industry collapsed, like so many on the west coast, due to over-fishing. The building was completely empty when we found it — we brought in the the whole working cannery with its steam, water, fish gutters, ice breakers, conveyor belts, etc. is an illusion to create the period atmosphere. Into the cannery shell we had transported machinery from all over Oregon. The main machine that Jack works beside was a monstrous fish-gutting contraption once called ‘The Iron Chink’, which at the turn of the century had replaced two hundred dextrous Chinese cannery workers. At the end of two days we had filmed our cannery labor dispute and disposed of over 1000 pounds of fish. During the first takes, the razor sharp spine of one of the thrown fish impaled itself into the leg of a stuntman who was taken to hospital. We stopped filming for an hour while the prop department de-spined the seemingly harmless missiles. I never imagined when I wrote the scene that pelting someone with a fish could be so dangerous. As I stood in the raised ‘office’ we had built inside the cannery, I looked down on the crew as they rearranged the props, machinery, lights, tracks, cameras. It seemed that the entire crew of 100 were working at the same time, many of them having been up since the early hours. Even the usually insular makeup department, in their rubber gloves, were helping out by tossing smelly fish from table to table.

Dennis Quaid (Jack McGurn) and Tamlyn Tomita (Lily Kawamura), Seattle

As the film trucks arrived in Seattle, the company moved straight to the location where the younger Jack and Lily crash ‘someone else’s wedding’. We had pre-recorded Mark Earley singing “Nevertheless” and “Love is the Sweetest Thing” back in Los Angeles and so, as always when doing music-based scenes, the atmosphere was very pleasurable, This was a welcome change of pace for the crew, many of whom were fast approaching exhaustion from the constant travel and long hours. The cannery scenes concluded our work in the northwest and the entire company moved to Southern California, for the internment camp set and the final part of our story. We had began the task of building the enormous 84 foot long internment huts in Portland by pre-fabricating them in our workshop to be shipped (with the 1000 window frames we’d built) to the desert at Palmdale. We had started clearing the land on August 1st and when we arrived on October 10th, it was ready for filming. In all, we built twenty-five 84’ huts (six with complete interiors); seven 84’ production huts (for electricians, makeup and hair, construction, set dressing, nurse’s first aid station, extras holding etc.); we built four 32’ huts, four moveable huts on trailers; a camouflage factory; two guard towers (moved each night to strategically placed cement foundations); two water towers. We erected forty-six 40’ power poles strung with 12 miles of rope to simulate electrical cable; twenty miles of barbed wire stretched across 3000 feet of fence. We dug 950 cement filled holes to hold everything down, as the fierce desert dust storms did their best to flatten everything we had built. Eight miles of electrical cable was buried in addition to the 17,000 feet of cable to light sets. Back in Los Angeles the studio accountants were concerned at our budget, but the brilliant Bob Colesberry performed miracles stretching our scarce resources to the maximum. When I first walked through the streets of the completed camp, examining the multitude of camera possibilities, I was fearful that I could never do justice to the work everyone had put in. Our first scene was in the Kawamura Hut, as the family respond to the riot outside. This was once again complicated by having eight players, each with their own dialogue in different parts of the room continually moving. To choreograph the master shot, with its many different camera positions complimenting the action was very satisfying, but the ensuing and necessary coverage of each character became a technical nightmare. Normally I can hold the twenty or so shots in my head for such a scene, but on this one I wasn’t completely sure and so I asked my editor, Gerry Hambling, to cut it together immediately to see if the jigsaw fitted together. Fortunately, it did. Many of our exterior scenes were divided in half, or sometimes in thirds, in order to take advantage of the low light at the beginning and end of the day. Filming in the middle of the day is impossible in the desert, with the hard sunlight flattening the photographic image and so we had planned each scene —going inside to shoot interiors in the middle of the day during ugly light. Each exterior shot had been worked out to the compass to allocate the best time of day to film. As our three Japanese ‘Andrews Sisters’ belted out the three part harmony of “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree”, the upbeat music of the scene was a welcome one as the crew, one by one, seemed to be collapsing, many of them working around the clock to prepare each set for filming. Peter Bloor, my gaffer electrician was sent to the hospital with pneumonia, the set decorator was in the hospital after a set fell on him, and the assistant set decorator collapsed with exhaustion after working too many 36 hours shifts. We also tried to show the change of seasons through the years of the camp by the gradual change in the neat gardens that had sprung up around the huts. As they say, “Give a Japanese a bucket of earth and he’ll make you a garden.” Dust storms regularly demolished our green houses, but the art department continued to work through each night to prepare our sets for the next day’s filming, including our snow scenes with the crushed ice machines spitting out the “freshly settled” snow. As the desert continued to throw real dust storms at us, we filmed the family at Mr. Kawamura’s graveside. For once the dust was right for our scene —at other times it only hindered us as the sand got into our equipment and eyes. During filming we sprayed over 3 million gallons of water to keep down the dust, as we had a taste of what the real evacuees had to endure.

We had lost everything we owned and everything we loved… it wasn’t possible to lose anything more… But Mama says a wasp always stings a crying face because we also lost Harry. It was our last winter in the camp. And our darkest.

LILY

We had been shooting in the desert for only three weeks, and it seemed a miracle that we had filmed everything. When I first saw our mammoth camp completed, I never thought that we had the time or imagination to do it justice. But on leaving we realized that not one small corner had failed to find its way on to film. Whether we captured the lives of the Japanese Americans who endured internment between 1942 and 1945, only the finished film will show. For the crew, we had shot a film in sixty-three days that should have taken ninety. For most of those days, the crew worked eighteen hours a day to accomplish an impossible schedule. If we succeeded or failed, we couldn’t have worked harder to do justice to the memory of the people who really suffered. We drove out of the camp for the last time, and within four weeks it was demolished: the lumber sold off, and the land returned to how we found it; just a barren corner of windswept desert. Much like the original Manzanar now is.

We had been shooting in the desert for only three weeks, and it seemed a miracle that we had filmed everything. When I first saw our mammoth camp completed, I never thought that we had the time or imagination to do it justice. But on leaving we realized that not one small corner had failed to find its way on to film. Whether we captured the lives of the Japanese Americans who endured internment between 1942 and 1945, only the finished film will show. For the crew, we had shot a film in sixty-three days that should have taken ninety. For most of those days, the crew worked eighteen hours a day to accomplish an impossible schedule. If we succeeded or failed, we couldn’t have worked harder to do justice to the memory of the people who really suffered. We drove out of the camp for the last time, and within four weeks it was demolished: the lumber sold off, and the land returned to how we found it; just a barren corner of windswept desert. Much like the original Manzanar now is.

Last Words

The extraordinary effort that goes into the making of a film, any film, is rarely appreciated or understood, which is probably how it should be. We filmmakers spend a couple of years of our lives creating and fine tuning a thousand tiny moments for an audience to experience in a couple of hours. Hopefully, some people will like what we do, and no doubt some won’t. There is also an extra responsibility in tackling subjects which are not of one’s owns experience. To many of our Japanese American cast and crew on Come See the Paradise it wasn’t just a movie, but part of their lives, To the rest of us we were filmmakers endeavouring to capture the elusive truth of the times and our characters’ lives. We were outsiders peeping through the cracks in someone else’s fence. But as Jack says to Mr. Kawamura, “What I can never be is Japanese. But I couldn’t love Lily more”. The title for our film came from a line in a poem by the Russian poet Anna Ahkmatova which I had scribbled down in a notebook a long time ago. It was so long ago that, however I tried, I couldn’t find the original so, before I wrote a word of the script, I wrote my own poem to try and say what I’d hoped the film would say:

We all dream our American dreams When we’re awake and when we sleep So much hope that grief belies Far beyond the lies and sighs Because dreams are free And so are we Come See the Paradise

On August 10th 1988 Congress passed the ‘Civil Liberties Act’, formerly apologizing for the camps and the war time incarceration of its Japanese American citizens. Alan Parker, Los Angeles, April 1990. Production notes for the film.

Afterwards

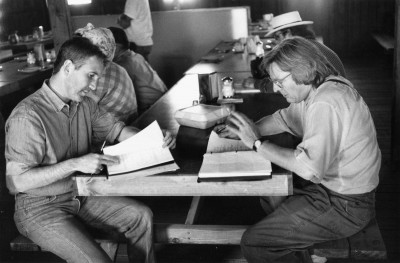

In our fraught, first week of filming we had large crowd scenes to shoot out at the old Portland Meadows race track. As Aldric ‘L’Auli’ Porter, our Samoan American assistant director and his asistant directors coped with the many vignettes, I spied, from my vantage point high on a camera rostrum, my producer Bobby Colesberry sitting atop a high pile of hay bales. He seemed to be deep in thought: the weight of the whole production on his shoulders, probably worrying as to how the hell he was going to pull off the large scale film we had planned with the small scale budget the studio had allocated. Bobby had been with me every single minute from the very beginning of this film, as he had been with Mississippi Burning the previous year. Over the walkie-talkie I asked if he could help out organizing the eastern flank of extras—he was after all one of the great assistant directors before he took up producing. Suddenly a big smile appeared on his face and he leapt up sure in the knowledge that he could do something useful, instead of being the studio’s punch bag.

Producer, Robert Colesberry and Director, Alan Parker: Palmdale, California

As he leaped off of the hay bales and waded into the extras, megaphone in hand, he suddenly collapsed and the entire production ground to a halt as the para–medics attended to him. Apparently his heart had briefly stopped beating and he had collapsed from exhaustion and, no doubt, more than a little stress. As the ambulance men took him off on a stretcher he looked up at me and said,“If I die, please don’t dedicate the film to me?” Luckily for all of us, they let him out of the hospital the next day. Unluckily for all of us, his heart stopped beating for good in 2004. Bobby had started with me as my first assistant on Fame and had gone on to produce excellent films with some great directors: Scorsese, Shlondorff, Ang Lee, Levinson, Benton, Joffé and Pakula, among them, as well as his ground breaking work on TV; The Wire and The Corner. I was fortunate to have him produce three films for me: Mississippi Burning, Come See the Paradise and The Road to Wellville. He was a great filmmaker.

All text © Alan Parker. All photos © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. Stills photography: Merrick Morton, David Appleby. Cinematographer: Michael Seresin