Angela’s Ashes

The making of the film by Alan Parker

They used to say that if you threw a brick in Limerick you’d hit a priest. These days the priests are not so plentiful, but if you throw a brick, you’re bound to hit someone with an opinion about Frank McCourt and his book. My personal impression is that everyone you meet in Limerick of a certain age falls into one of two distinct camps. Half of them claim that this uppity, now affluent, Irish Yank exaggerated his childhood plight. The other half of Limerick seemed to have lived next door to the McCourts. Anyone who doesn’t fit into these categories either has their own book to sell or has absolutely no memory of it ever having rained in Limerick.

The first time I visited Limerick in April 1998 I was armed with a bundle of maps which we had downloaded from one of the ‘Angela’s Ashes’ fan web sites. This particular web site was all the more remarkable, I thought, because it was Japanese. Why a culture so different to the Irish should have been so taken by Frank McCourt’s story intrigued me no end. I walked the streets so carefully mapped out and lovingly flagged by the Japanese fans who were obviously obsessed with every little detail of Frank’s book: “First residence: Windmill St. (until Oliver’s Death)”; “St Joseph Church (First Communion, Confirmation)”; “Lyric Cinema (closed 1964, now parking)”.

As we walked the route, we found that even the landlord at South’s pub had started to pin up Polaroid photos of himself hugging strangers with wide, white-toothed, un-Irish smiles. No doubt the ghosts of Malachy Sr., Uncle Pa and Mr Hannon, supping their Guinness in the snug were wondering why their local had suddenly become so popular. For four Irish punts you could even go on an Angela’s Ashes walking tour, “Daily at 2.30 pm”, the flyers pronounce. You can spot bands of “McCourties”, clutching their well-thumbed copies of Frank’s memoir, regularly walking up Barrack Hill in search of Roden Lane and stopping in their tracks, baffled that it’s no longer there. Frank was very candid about his sudden fame. He said, “I was a teacher all those years. I added up that I taught 33,000 lessons to 11,000 kids and then I wrote a book and now I’m flavour of the month, they can’t get enough of me. And later on they’ll say: who? It’s the express version of notoriety.”

A year had passed since I had first read an early publisher’s proof of Frank McCourt’s book and in that time it had won the Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction and was already on its way to becoming a phenomenal success. It sat atop the New York Times hardback bestseller list for 117 weeks and the book, currently, has been published in 25 languages selling over 6 million copies in 30 countries.

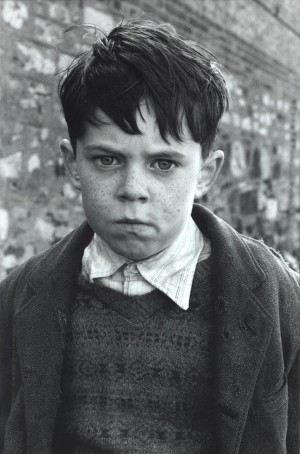

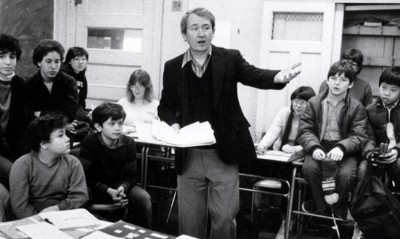

Frank McCourt and Joe Breen (Young Frank), Dublin

I had expressed an interest in acquiring the rights to the book when it was first published but learned that they had been snapped up by the canny producer David Brown, who was to produce the film for Paramount with the prolific Scott Rudin. An early script had been written by the Australian writer Laura Jones and, once I was asked to direct it, I began work on my own draft of the screenplay. Everyone who has ever read Frank’s beautiful memoir will have come away with a thousand images of their own which is always daunting for a filmmaker because each reader has their own movie locked away inside their head. The unique quality of the book is in the ‘voice’ that Frank found to tell his story: the wisdom of a retired school teacher, told in the first person, present tense, from the perspective of a young child. For decades, he claimed, he had been scribbling about his childhood, filling a duffle bag full of notebooks with his writings in between his day-job teaching English at New York’s Stuyvesant High. “I didn’t get round to writing (the book) sooner,” he said, “because all those years I was too busy marking other people’s essays. Also the timing wasn’t right. My mother had to die and I think I had to grow up – and that took me a long time.” Also, he says, he couldn’t find his own voice – “I was trying to write like Evelyn Waugh or James Joyce.” The unique present tense voice in his book Frank has attributed to visits from his granddaughter Chiara. “I was watching her, how immediate she was. She had no hindsight, no foresight. She was just completely immersed in what she was doing. Then I started writing in the voice of a child, immediate, urgent, and without hindsight or foresight. Children don’t lie.”

Originally, Frank was going to bring the story up to 1981, when his Mother died. Hence his title: “Angela’s Ashes”. It was his editor at Random House who suggested the nice circular trip: born in New York, go to Ireland, return to the states. But he had his title and didn’t want to let it go.

Adapting any famous literary work for a filmmaker is problematic in that, in the compression to a manageable cinematic shape, inevitably, certain characters and situations will be excluded. If I had filmed the whole book people would have been sitting in the movie theatres for eight hours. I met with Frank for lunch and talked about the pitfalls of any screenplay and he was, as he always is, most generous, constructive and totally un-precious about his words. I think originally he had considered writing his own screenplay but eventually concluded that it would be better if fresh eyes and legs took on the task. Also, it’s painful for any writer to take the necessary cleaver to much loved passages. How do you make the choices? Mr Timoney or Mr Hannon? Theresa or Patricia? Mr O’Neill or Mr Benson? South’s pub or Gleeson’s? However (always the caring English teacher), Frank was encouraging throughout the scriptwriting process and most complimentary on Laura’s and my finished efforts.

In Limerick I walked the streets many times from South’s pub, to Leamy’s National School, to the General Post Office, retracing Frank’s own steps as we tried to piece together Frank’s life and figure out just how to replicate his world on film: the Limerick of the 1930’s and ‘40’s. Although Leamy’s building was intact, it had been closed down as a school in 1952 and its interior ripped out and converted into modern offices. Roden Lane itself, in many respects the heart of the story, (the book’s “Ireland” and “Italy”), had long gone, as had most of the worst slums mentioned in the book. However, the elegant Georgian crescent on O’Connell Street, just down from South’s pub, has survived, remarkably period-correct, dominated as it is by the imposing statue of the great Catholic liberator Daniel O’Connell now standing atop a column originally built for some forgotten English king. We filmed much that revolved around Frank’s world here on this historic crescent..

The nearby St Joseph’s and Redemptorist churches were out of bounds to us, however, as the clergy would not grant us permission to film inside, or indeed, even outside by the iron railings. We assumed that the Church leaders were less than pleased with how their predecessors of some fifty years ago were portrayed in the book and had therefore decided not to co-operate with us. The Franciscan Church on Henry Street was, initially, a tad more welcoming. Since the character Father Gregory was portrayed as one of the few compassionate and caring adults in Frank’s memoir, the last bastion of the young man’s fragile faith, we were optimistic that they, among all the churches in Limerick, would allow us in to film. As it transpired, their welcome lasted about a week, until they were also “persuaded” by the Limerick ecclesiastical powers-that-be, to disinvite us from filming in their church. This rejection was extremely disconcerting to us as these scenes were, of course, pivotal to our story. However as one door closed another opened when a different diocese (and governing body) in Dublin welcomed us to film in their churches. Apparently they felt sufficiently distanced from the story not to feel any collective guilt for the Church’s behaviour towards the poor of Limerick in the 1930’s.

Although, at one end of the spectrum, it has been said that Frank McCourt had done for Limerick what James Joyce had done for Dublin, and The Irish Times had even dubbed him “our first Irish Dickens,” not everyone in Limerick has embraced Frank’s book. Some saw it, at least, as an attack on their beloved Limerick and, at most, as a rag bag of New York Irish bollix. Frank has always made it clear that the book was not a personal attack on Limerick. He didn’t even see it specifically as being about Limerick, but more importantly as a book about poverty. “My childhood gave us aspirations and dreams,” he said, “But it lowered our expectations too. And lowered our self-esteem. When you’re used to nothing, you’re satisfied with very little. We didn’t dream beyond a bowl of soup.”

During the months of preparation my Production Designer, Geoffrey Kirkland, and I traveled all over Ireland to seek out our locations. One of the negative aspects of the new thriving economy in Ireland is that the Celtic Tiger might be good for business, but it’s made it a lot more difficult to make period film there. What little period architecture the country once had has either been torn down or rebuilt in a modern manner, and only the most obvious Georgian architecture survives intact. All too often, ugly, modern bungalows thumb their noses from once pretty green hillsides that they now disfigure. Once monochromatic streets are now transformed by a curious national penchant for bright purple, yellow and pink exterior paint. In short, a nightmare for a film art department set the task of recreating the world of sixty years ago. Limerick, the centre of our story, offered us the beautiful Georgian Crescent, with O’Connell’s statue, adjacent to South’s pub and the River Shannon, which is the damp heart, and, in many ways, the silent villain that slithers through our story. Even the Shannon itself offers fewer and fewer riverbank views as the city hurtles towards modernity, cluttering the historic riverscape with contemporary eyesores. But the ancient river still has a raw and aggressive power that roars through the centre of the city as well as our film. I had some experience working in Ireland on The Commitments and, as with that film, it was obvious that a patchwork quilt, a mosaic of different places, would have to be put together to accurately replicate the Limerick of fifty-odd years ago.

For these reasons we decided also to film in Cork, a city which has retained its narrow, cobbled streets and is also, handily, close to Cobh Harbour which for a century and a half had seen a hundred thousand Irish families emigrate to the U.S; and to where Angela, Malachy, Frank, Malachy Jnr, Oliver and Eugene McCourt conversely, and perilously, return. The bulk of our filming, however, was to be done in Dublin, where the busy city offered up the most options needed for our film locations. It is also close to Ardmore, the main Irish studios, where we were to build many of our interiors. Most of the rooms that the large McCourt family shared were tiny, and the impracticality of a hundred and fifty film crew squeezed into such spaces ruled out the use of real interiors. It was also clear that the exterior of “Roden Lane,” in which much of our story was centred, had to be built as a set since these once quite common, narrow alleys had disappeared with Ireland’s new-found affluence. To this end we built the muddy, cobbled “Roden Lane” set with its thirty dilapidated cottages on an empty Dublin building-site situated just a hundred yards from the River Liffey. The set took eighty carpenters, plasterers, painters, greensmen, and dressing props fourteen weeks to build and we filmed on it for scarcely two weeks. I can only think that the future bands of “McCourties,” their “movie version” web site maps in hand, are going to be disappointed visiting the film’s “Roden Lane” on Benburb Street, because alas it took just two days to demolish it and return it to a building site.

Once I had finished my draft of the script my next priority was casting. I met with Emily Watson in New York where she was filming Tim Robbins’ Cradle Will Rock. She was the only actress I had in mind when thinking of Angela – I had greatly admired her wonderful “nerve- end exposing” performance in Lars Von Trier’s Breaking the Waves, and her powerfully subtle work in Jim Sheridan’s Northern Irish film The Boxer. At the time I hadn’t yet seen her as Jacqueline Du Pre in Hilary and Jackie – a performance which would bring her a second Oscar nomination. After a short meeting (and the bonding revelation that we both supported Arsenal), I was convinced she was our Angela. Emily’s complete lack of pretentiousness is quite compelling. The part of Angela meant that she would have to look less than glamorous wearing distinctly unbecoming costumes and make-up, ageing fifteen years through the course of the story and chain-smoke nasty Woodbines for three months of filming. None of this phased Emily one bit.

I met with Robert Carlyle in London for a drink. Robert had declined lunch, having recently having returned from Slovakia and the Czech Republic where he had been chewing on human body parts for Antonia Bird’s cannibalism film, Ravenous. Bobby was very keen to portray Malachy McCourt Snr., Frank’s feckless, alcoholic father, a man who is sadder than he is evil. A man with great dignity – every morning he gets up, shaves, dresses, puts on a collar and tie, looks for work, doesn’t get it, goes to the pub, in an endless cycle of despair. He is utterly hopeless, but the kids never have a bad word to say about him, despite the penury and pain he causes them with his negligence and irresponsibility. Frank had described his father’s ‘odd manner’ in the book – an edge, a sense of danger. To still make this man sympathetic to an audience was Bobby’s biggest challenge because it would be too obvious to paint Malachy Snr as the sole villain of the piece, because he is clearly a victim himself. The intensity and concentrated power in all that Bobby does can sometimes shake you as a director and it’s hard not to be impressed with his work. Most people probably know him as “Gaz,” the unemployed steel worker in The Full Monty or the manic “Begbie” in Trainspotting, but other images of his performances had always stayed in my head: his portrayal of the skinhead psychotic in TV’s Cracker; in Michael Winterbottom’s Go Now, his work as a multiple sclerosis sufferer is one of those performances that you can’t watch without dropping your jaw; the gay sex scene in Antonia Bird’s Priest; his work in Loach’s Riff Raff and Carla’s Song…….the list goes on and on. Bobby is very acerbic about his profession, “It’s funny acting. I’ve worked with people who spend the whole time pissed and don’t give a shit, and with others who pace up and down worrying every night – and you wouldn’t necessarily know which is which.”

The casting of young Frank presented extra difficulties because we were going to need three different boys to play Frank (aged five to eight), Middle Frank (aged 10 to 13) and adolescent, Older Frank – not to mention three different Malachys, Michaels and Alphies). Apart from having to convince the audience that these three Franks are the same boy, accurately resembling one another in physiognomy and manner, the transitions of the ageing process had to be seamless. There was always the danger that the audience would invest so much emotional commitment to the first and youngest Frank that there would be a sense of loss once Middle Frank takes over and the viewer realises that the youngest boy has vanished from the screen. I paid a lot of attention to the transitions from young, to middle, to older Frank and, hopefully, in a blink, the audience accepts these transformations.

Our casting directors (John and Ros Hubbard and Juliet Taylor) had all worked with me before and I was lucky to benefit from their wisdom and enterprise. In looking for the children Ros Hubbard held ‘open calls’ in Limerick, Ennis, Tralee, Dingle, Tipperary, Cork, Kerry, Waterford and Dublin. Over a two month period they saw close to 15,000 kids, patiently sitting and reading lines with them, narrowing down and videotaping them for me to choose from. We ran ads for the auditions in newspapers, stuck signs on lampposts, and ran competitions on the radio in order to cast our net as wide as possible. Joe Breen, who plays young Frank, answered just such an advertisement in The Irish Times. A farmer’s son from County Wexford, he woke early on the day of his audition, helped his father to milk the cows and then travelled two hours up to Dublin for our giant open call. I singled him out from the thousands who turned up and subsequently called him back on three more occasions to videotape and work further with him, going through the scenes and encouraging him to improvise, to be as natural as possible – not to act but to be himself. From the first day he effortlessly took to his new career (whilst still milking the cows before coming to the set). He is a beautiful, unspoiled boy and bright as a button. Not only was he always word-perfect with his own lines, but took delight in correcting the adults on theirs.

Ciaran Owens, from Killeshandra, County Cavan, who plays Middle Frank, came to his part through a more conventional route. The youngest of five sons, his brother Eamonn Owens had brilliantly portrayed the title role in Neil Jordan’s film The Butcher Boy. (In Angela’s Ashes, Eamonn plays the role of Frank’s friend, Peter Dooley – “Quasimodo.”) It was ironic, therefore, that after casting our net so widely amongst so many newcomers we should choose Ciaran, who had already acted with his brother in a number of Irish productions.

Michael Legge, who plays the older, adolescent Frank, comes from Newry in Northern Ireland and had done some television and theatre work before coming to Angela’s Ashes. He has great subtlety and application and, as with all good actors who make things look easy, there is a fierce intelligence at work. In many ways he has the hardest job of the three Franks as he has to follow young Joe and Ciaran, who have the lion’s share of the film, dominating the first two acts. Cumulatively the two young ones are a hard act to follow. When we shot the penultimate scene where older Frank stands in the street outside Grandma’s house and looks back at the images of his younger selves, Ciaran and Joe silently staring back at Michael, I realised how lucky I was to have found not one, but three, great Franks.

The age progression in the narrative also meant that surrounding siblings and friends of different ages had to be cast: young, middle and older Malachys, Michaels, Alphies, Paddys, Willies, Fintans, etc, I realise that we were fortunate to have had fifteen thousand young actors from our original casting from which to cull.

Our film had the advantage of being financed by two studios, Paramount and Universal, and so we had the luxury of moving this mammoth travelling circus around Ireland. Luxury is probably not the best word because three months of soggy socks and dripping macs meant perpetual flu but, curiously, we got used to it. I don’t think I ever had a conversation with someone from the crew during the three months shooting without them blowing their noses mid sentence.

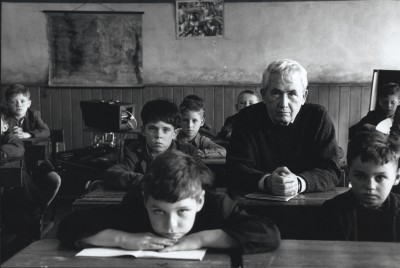

Harrowing and bleak as our story is at times, Frank’s book, of course, is also full of humour too, and I tried at all times to lighten up situations which, on the surface, might appear grim. We started the shoot with the various scenes in Leamy’s National School, actually filmed in the empty St Kevin’s (cont) School in Dublin. Frank McCourt (the real one) visited the set and watched from a corner. Joe Breen, playing young Frank, eyed with some suspicion the white-haired man standing unassumingly at the side of the classroom. I said to Joe, “Do you know who this gentleman is?” and Joe answered, “Yes, he’s me when I’m older.” Frank told me he was uncomfortable on the set. He felt awkward – as if he was intruding on his own life and being jolted back to the past surrounded by shaven heads and ragged clothes. He said he was going down the pub with Emily, fearful as he was that the master would turn on him with his stick.

Emily Watson (Angela), Joe Breen (Young Frank) and Shane Corcoran (Young Malachy) at the St Vincent De Paul Charitable Society

I had decided to shoot some of our more harrowing scenes early on, to prepare all of us for what follows and to familiarise the younger members of the cast with the more serious, bleaker parts of our story. Geoffrey Kirkland, our Production Designer, and Jennifer Williams, our Set Decorator, had converted another derelict Dublin school into the St Vincent De Paul Charitable Society, where Angela suffers the humiliation and indignity of begging from the assembled “V de P” officials. Emily and the boys standing erect, fragile and vulnerable, like a Victorian painting by Yeames, overshadowed by the massive presence of the crucifix hanging above them on the wall.

The grim graveyard scenes followed, as Angela and Malachy bury, first Oliver and then his twin, Eugene. As an actress, Emily has an extraordinary ability to suddenly cut off from the real world and concentrate totally on the scene. She can be talking to you as herself and then as the scene begins she would walk away to be by herself for a short moment and then she’d begin the scene stopping your heart as she stifles the pain showing Angela’s unimaginable suffering at the loss of yet another of her children. The delicate knife-edge between an actor’s real self and the illusion they are conjuring up for the camera can be quite a burden. As Emily put it: “You get to the end of the day and you order room service and hope that the work was good, but something’s nagging in the back of your mind. Something awful happened. And you think, “Oh yeah, my baby died.”

We then settled into two weeks of our interior work at Ardmore Studios. The tiny sets all had floating walls to open up this confined cramped world to the camera, lights and the dozens of attendant crew. The old chestnut about avoiding working with animals and children became very real as Emily and Bobby juggled the various babies, whilst battling the fleas. Emily said she sometimes felt more like a child wrangler than an actress as she wrestled with her tiny wriggling co-stars who gathered little pleasure in enduring repeated takes. At the end of a day’s filming, Emily had difficulty lifting her arms up, aching as they did from holding her movie offspring. Like all good actors, both Emily and Robert used the discomfort to help with their performances. Both of them are unselfish in their acting and the nerve taxing chore of nursing an uncooperative, wailing infant ensured a certain reality in the scenes. Both Emily and Bobby have a humility in their acting that makes it so pleasurable for a director. They have an extraordinary ability to concentrate and to give generously to those around them so that the work is never about themselves but rather about the collective scene. Watching the two of them coping with the flailing arms and wriggling bodies, patiently waiting for the screaming to stop in between takes, and still managing to get their own lines out, deserved all of our admiration. I have to say that these were the most difficult scenes I’ve ever directed with young children and I’ve done a considerable amount of filming in this area. Although a shrieking child might be what you’re after for the scene (and as a director, greedily you grab this distress on film) you have to keep reminding yourself that it’s not just the illusion of film and that close by, behind the set stands the real mother of this small child, suffering considerably herself as her offspring shed real tears for the camera.

From Ardmore we moved on to Cork, where the cobbled alleyways and steps added to the mosaic of Frank’s world. With the help of the local Gardai we were able to close down some of the longer runs of the city and re-dress each and every shop window and doorway. Above us, the rain machines poured down – quite ironic considering the less than dry Irish climate, but the machines allowed us the continuity needed on film and the artificial rain photographs more clearly than the erratic, and finer, real Irish drizzle. Although we were building “Roden Lane” in Dublin, I had also found streets in Cork with period detail which would be our “Windmill Street” and the narrow archways that would appear to be adjacent to Roden Lane in our “joined together” story courtesy of the illusion of editing. As each street would have resonance in all three acts of our story, each scene had to be repeated with the three differently aged Franks and Malachys.

From Cork we moved to Limerick with a brief respite for a day’s filming at Cobh Harbour, fifteen miles from Cork. For two centuries the deep harbour at Cobh was the historic departure point for thousands of Irish families leaving by ship for the U.S. It made for a touching scene as we watched our own small family make their way up the same hill that so many families had descended on their way to America.

The Crescent, O’Connell Street, Limerick. The architecture is pretty intact and “period correct’. The rain is ours.

Arriving in Limerick was an odd feeling. It’s an exaggeration to say that there was enmity towards us making the film in the city where the story is based, but I think it’s fair to say that there was some trepidation on our part, a feeling that we were not entirely welcome. Many of the people of a certain age had thought that Frank had disparaged the city in his book. As Frank says, “My mother hated me uncovering the past: the only place for confession is to a priest, she thought; she wanted curtains drawn over all the poverty and sordidness.” Certainly the hierarchy of the church had made its stand by refusing us permission to film inside Limerick churches but the local Redemptorist priests were most cordial as they passed the camera crew, giving us a smile and a wink of encouragement — even though their bosses, the Monsignors in Kilmoyle, appeared to view Frank McCourt as the anti-christ.

If there was ever any enmity amongst the locals it soon evaporated as we took over the city centre for three days. Traffic ground to a halt for hours at a time, with few honks of protest, and children took the day off from school to watch the proceedings (sometimes with the blessing of their teachers, sometimes not).

Our Irish Costume Designer, Consolata Boyle kept her cool as we coped with our largest crowd scenes. The wonderful bonus of having non-professional extras is that they bring an honest naturalism to the proceedings. The downside is that, once comfortable in their authentic period clothes, they had to be reminded that they can’t take them home at the end of the day. We lost a few good suits and a dozen pairs of boots as many of the extras mistook the costume department for an Oxfam shop where they could help themselves. We filmed for three days on the rain-soaked (courtesy of our rain machines) Crescent and each evening we would retreat to South’s pub to down a Guinness and rub shoulders with the ghosts of Malachy and Uncle Pa.

Our other priority in Limerick was of course to capture shots of the River Shannon. At first light each morning and each evening as light fell, we would position our camera at one of the few spots that afforded a view uncluttered by modern architecture, using small boats to ferry the effects machines to drift smoke into the backgrounds to soften and disguise any contemporary structural embarrassment. Similarly, each evening as the light fell, we repeated the process until all the shots needed for the film were in the can.

Our next week of location shooting took us out to the vast mental hospital of St Ita’s in Portrane. Built at the turn of the century. this mammoth complex once housed five thousand patients. Although still in use, albeit on a much smaller scale, large areas of this sad and mysterious building had become empty and dilapidated, offering up a musty, ready-made, film set. Here we filmed the City Home Hospital interiors as Frank recovers from typhoid and conjunctivitis. The wide corridors also gave us the Henry Street Post Office set where older Frank verbally duels with the officious Miss Barry. Denied the real Redemptorist Church in Limerick, we were able to film this interior in the Church of the Oblate Fathers in Inchicore, where the irate priest harangues the boys in the congregation for “interfering with themselves.” It’s always difficult filming in a place of worship, as a hundred film crew noisily go about their business – particularly for a film which takes place in a period before Vatican II, which entails removing the front altar, disrupting the ‘serious business’ end of the church. At first, everyone tip-toes about, speaking in reverential whispers. But as the day’s filming progresses– as pews are pushed out of the way to accommodate camera dollies, as cranes, light-frames, make-up mirrors and sound carts are dragged in and trays of bacon rolls and cups of tea consumed. (In my experienece, absolutely nothing on God’s earth can interrupts or abate a film crews appetite) With the best of intentions, reverence gradually slips away as the building is temporarily mugged of its religiosity by this secular bunch.

We built he interiors of Grandma’s house were built by Geoffrey Kirkland and his art department at Ardmore, as were the New York tenements in the opening scene of the film. The interior scenes of the New York tenement, with Frank and Malachy changing the twins’ “shitty” nappies, were very harrowing to film. After many weeks of filming the young boys playing the twins, Oliver and Eugene (Sam and Ben O’Gorman, age 2) had got wise to the mechanics of filming and had obviously made the joint decision that they hated it. Consequently they screamed very loudly -– louder than any child had ever screamed, their faces turning to considerably sized beetroots as they practised bursting every corpuscle, the moment they were brought anywhere near the film set. As we had already established them quite clearly earlier in the film, shooting as we did out of sequence, I had to persevere, even though these young “thespians” had decided that the acting life was not for them. After three days, many bags of chocolate biscuits, a great deal of patience considerable pints of Guinness later, we had the (very authentic and painfully real) scenes in the can.

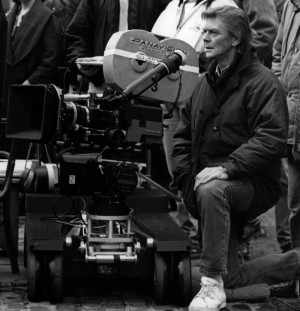

Alan Parker helping out the art department.

For Limerick Railway Station we used Pearse Street Station in Dublin, borrowing the period steam trains from the Irish Railway Preservation Society. We filmed through the night, as Mam, Frank, Malachy and baby Alphie await Dad’s return from England. As the smoke belched out of the locomotive’s chimney and billowed down the platform, I was reminded how much I, like most filmmakers, love filming steam trains. Just sniffing the coal-dust and oil in the air somehow ensures a successful shot. Our final two weeks were spent filming on our purpose-built set in the centre of Dublin. As I mentioned before, the narrow slum alleys, “the lanes” of Frank’s memoir have fast disappeared under the bulldozers of the newly affluent Ireland necessitating the building of our “Roden Lane.” I think the filmmakers of my generation have relished the fact that we took filming back into the streets and away from the studios, but for control and sheer pleasure of filmmaking, for a director, there’s nothing like a locked studio set. It’s a joy being able to concentrate on the scene at hand instead of battling, as we usually do, the unrelenting intrusions of the rubber-neckers and intrusions of daily life in a real city. The Roden Lane set also housed a number of interior sets and work here was probably the most enjoyable for the crew. Filming wrapped on December 22nd, ’98, having taken 75 shooting days to complete.

My principal collaborators on Angela’s Ashes had worked with me on many of my films over the last twenty-five years and the film is as much theirs as mine. They are Director of Photography, Michael Seresin; Production Designer, Geoffrey Kirkland; Camera Operator, Mike Roberts; Line Producer, David Wimbury; and Editor, Gerry Hambling.

During the editing process I usually experiment with a “tool kit” of music. On this film it was a particular pleasure as John Williams had agreed to do the finished score. I consequently laid up a miscellany of John’s music, culled from his previous scores, to help me judge the ebb and flow of scenes but principally to aid the “spotting” of just where we were going to need music. I showed John an early cut of the film in June and, after finishing his latest Star Wars opus, he began work on our score. In Los Angeles, the music was recorded at Sony in Los Angeles —the famous old MGM music scoring stage where the musicians forbid cleaning the dust from the old studio walls and rafters lest it spoil the unique sound of the room. (It’s either a wonderful superstition or a great way to keep the maintenance bills down.) I try not to fill these production notes with meaningless hyperbole, but I have to say that working with maestro Williams was a privilege. However aware one is of his colossal talent, it’s still an extraordinary experience to watch him work. His sensitivity, wisdom, graciousness and total, effortless control of the task of scoring for film is awe-inspiring.

As I said earlier, adapting any famous literary work is a daunting experience because every reader of Frank’s memoir has their own movie locked away inside their head. For those of you who haven’t read the book, I hope you enjoy the film afresh. For those of you who have, I hope the images in the film coincide with some of your own.

Afterwards

The above piece was written in September of 1999 after shooting and before the film was released. After re-reading these notes, I was saddened by the mention of Mike Roberts, my camera operator who died in 2000.

I made eight films with Mike and he is sorely missed by me and. I’m sure, by the other directors who worked so well with him—Attenborough, Jordan, Joffé, Spielberg, Hallstrom, Zinneman. Although he had no formal arts training his understanding of composition and light was instinctive and intuitive, as was his mastery of subtle and artful camerawork that could add finesse, power and energy to any shot.

Camera Operator, Mike Roberts 1939-2000

A wiry slender man, his face craggy and leathery from the wind and the sun of a thousand locations, he had an extraordinary gracefulness and agility — or as Neil Jordan described him, “ that lined, gypsy face, with the steady blue eyes and the thin hands that guided the camera to the magic of every shot.” As the camera swooped and dipped across a set, balanced on a small platform Mike would twist and pivot, gently shifting his balance from one leg to the next, his face glued to the camera.

He was also extremely brave. No matter if he was filming a Khmer Rouge explosion in The Killing Fields or hanging from a tank on Indiana Jones, riding a raft on the Iguazu Falls on The Mission or facing collapsing walls of a burning church on Mississippi Burning, he never moved from the camera eyepiece for a second.

The poetry of camera movement — with subtlety, never bringing attention to itself —combining elements of movement of the dolly on its tracks, the swooping of the crane arm, the delicate combining of all these with the tiniest of movements of the zoom is seldom seen in films these days. Mike was one of the pioneers and one of the great exponents of his art.

David Puttnam once remarked, “If ever there was proof that film is a collaborative art form, then Mike Roberts is it.”

Text © Alan Parker. All photos © Paramunt Pictures, Inc / Universal Pictures, Inc. Stills photography: David Appleby, Bill Kaye. Cinematographer: Michael Seresin.

After, Afterwards

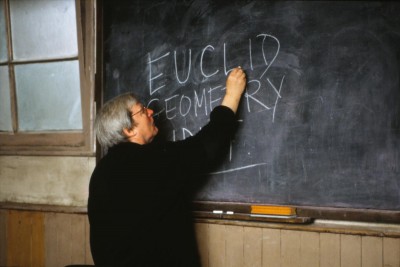

Frank McCourt, teaching at Stuyvesant High School, New York, 1983.

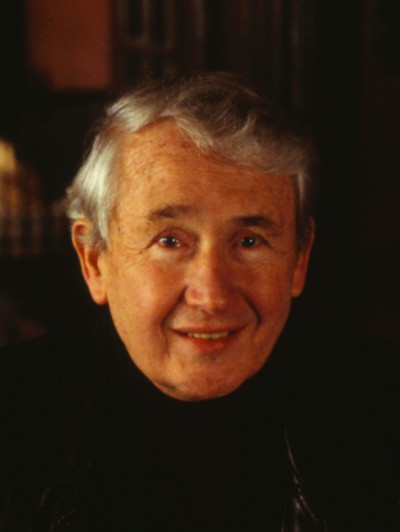

Frank McCourt died in 2009. He visited the set of our film just once: a gracious and generous man, he quietly encouraged everyone he met.

Success had come late to Frank, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1997, after a lifetime of teaching. Praised as he was for his writing, he was proudest of being a teacher — chronicled in his book ‘Teacher Man’ — so it was fitting that after his death the New York Department of Education opened the Frank McCourt High School for Writing, Journalism and Literature.

Frank McCourt 1930-2009

Your mind is your house and if you fill it with rubbish from the cinemas it will rot in your head. You might be poor, your shoes might be broken, but your mind is a palace.

Mr (Hoppy) O’Halloran. Angela’s Ashes