INTRODUCTION TO HENRY SCOTT IRVINE’S PROCOL HARUM: GHOSTS OF A WHITER SHADE OF PALE

By SIR ALAN PARKER

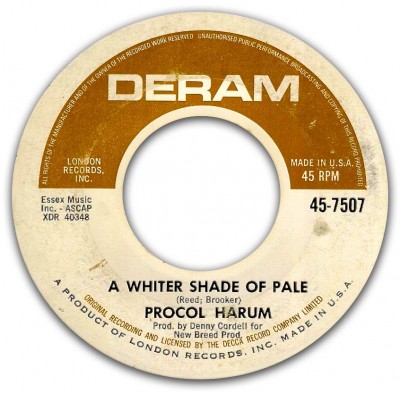

Let’s face it, Procol Harum’s A Whiter Shade of Pale is an odd song. Odd enough that anyone who has been anywhere near a radio, Walkman or iPod in the last forty five years almost certainly would have listened to it.

Let’s face it, Procol Harum’s A Whiter Shade of Pale is an odd song. Odd enough that anyone who has been anywhere near a radio, Walkman or iPod in the last forty five years almost certainly would have listened to it.

It entered our lives out of nowhere. To misquote the poet Philip Larkin: it came upon us in the summer of love, between Apollo1 and the Beatles’ eighth LP. It was a tough time to make a debut, because 1967 was a great year for music. Apart from the Beatles there were Otis, Aretha, Dylan, The Who, The Doors, The Kinks, The Animals and Cream. Pink Floyd went quadraphonic, the Stones were busted at Redlands, Hendrix burned his guitar at Finsbury Park and, miraculously, Britain even won the Eurovision song contest that year with Sandy Shaw.

With all this competition, this brand new band with the funny name and even odder song topped the UK charts for six weeks and soon became a worldwide hit, selling ten million records and spawning a thousand cover versions. The BBC says it went on to be the most played song in 70 years. It certainly was the most played song during that summer of love, as I bore witness, along with any song from Sergeant Pepper coming a close second.

My own connection to AWSoP (as the aficionados call it) is somewhat nebulous. Apart from (or maybe because of) being one of the nuts who couldn’t stop playing the song that summer, it subsequently found its way into my film The Commitments and later I had the pleasure of working with Gary Brooker on my film of Evita. And, like many others, it was played at my wedding. Except we were in Austin, Texas and it was sung by the great country-blues singer, Toni Price, with the lyrics taped to a mic-stand and the accompaniment on steel guitar.

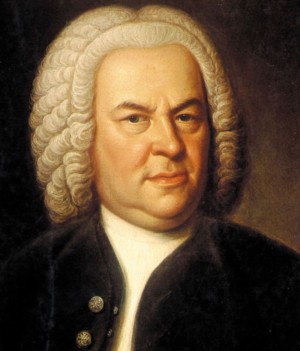

In The Commitments, we were a tad disrespectful. Jimmy Rabbitte, the young band’s manager in the story, visits the keyboard player, Stephen, in a church where he is playing the organ. The opening notes of AWSoP ring out and Stephen says, “Great intro, eh?” “Yeah they nicked it from Marvin Gaye” says Jimmy.” “He nicked it from Bach” counters Stephen. OK, we meant Percy Sledge, a mistake which we turned into a joke later, when Stephen is in the priest’s confessional. Personally I never got the Sledge connection. I was working as a copywriter in advertising at the time and wrote Hamlet cigar commercials, where we used the Air on a ‘G’ String music played by Jacques Loussier, so I always assumed it was that. It’s not, of course. I was also told it was inspired by Bach’s Sleepers, Awake. However, I am reliably informed that anyone who throws their hands at an organ keyboard will come out with something owed to Orgelbuchlein— Bach’s Little Organ Book.

After singing the first verse, Jimmy Rabbitte goes on to say, “Poxiest lyrics ever written.” Well, they are vexing, perhaps, or mysterious, elusory, and some think, impenetrable, but frankly, that summer we never worried too much that they didn’t make immediate sense. We reacted to the elliptical poetry the same way we did to A Day in the Life — as beautiful words that filled your head with images that just let your imagination fly: the more abstruse, the better. It meant just what you wanted it to mean. Those were the unique times in which the song was born.

After singing the first verse, Jimmy Rabbitte goes on to say, “Poxiest lyrics ever written.” Well, they are vexing, perhaps, or mysterious, elusory, and some think, impenetrable, but frankly, that summer we never worried too much that they didn’t make immediate sense. We reacted to the elliptical poetry the same way we did to A Day in the Life — as beautiful words that filled your head with images that just let your imagination fly: the more abstruse, the better. It meant just what you wanted it to mean. Those were the unique times in which the song was born.

That’s not to say people haven’t wracked their brains these last 45 years to offer meaning to Keith Reid’s mesmerizing poetry. Over the years, people have offered up explanations from drunken seduction, and drug overdoses, to necrophilia, to Arthur Miller’s tale with Marilyn Monroe. My favourite was the one about the violated nuns escaping the Nazis. Sounds like a good movie.

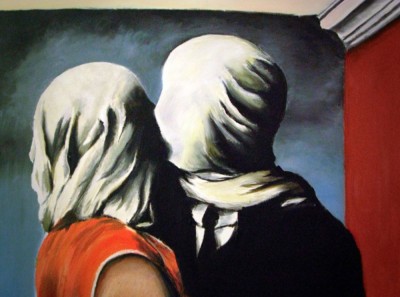

‘The Lovers’ by René Magritte, (1928)

As I got older and more pretentious, I could see the influence of André Breton, Lewis Caroll, Chaucer, Milton and Magritte. And less pretentiously, I think, maybe it’s a grab-bag of juicy references that Reid had jotted in his notebook— like William Burroughs’ ‘cut-ups’, as practised by Dylan and Bowie. Random thoughts, fragments of ideas, clusters of words, fitted together like a surreal jigsaw and scribbled down into four stanzas that became one of the most beautiful rock songs ever written.

When the seldom performed third and fourth verses came to light it was hailed by one journalist as, “the most useful piece of clarification since the cryptographers of Bletchley Park broke the Nazi Enigma code during the second World War.” The view was that the last two stanzas explained everything that had gone before, as the metaphors come full circle and the drunken seduction is consummated.

Then I was fortunate to work with Gary Brooker on Evita, where he played Peron’s Foreign Minister, Juan Atilio Bramuglia. Even if you watch the film with your eyes closed it’s impossible not to recognize Gary’s extraordinary, unique voice. On the day he finished filming, the crew gathered round for a drink to say goodbye. They peppered him with questions about AWSoP and he sang the final fourth verse, which he said made everything clear. The crew and I stood in a circle surrounding Gary in silence as he finished. All of us, it has to be said, were none the wiser, which for me, is as it should be.

In the final scene of The Commitments, Jimmy Rabbitte, looking in the mirror, has an imaginary conversation with Terry Wogan as to what he has learned from his foray into the music business.

JIMMY

Well, as I always say, Terry: We skipped the light

fandango, turned cartwheels ‘cross the floor, I was feeling

kind of seasick, but the crowd called out for more.

TERRY

That’s very profound, Jimmy. What does it mean?

JIMMY

I’m fucked if I know Terry.

Sir Alan Parker, June 2012