PINK FLOYD THE WALL

The making of the film, brick by brick

To be honest I should never have made Pink Floyd The Wall – it was a bizarre accumulation of events that left me with the directorial responsibilities. It’s not that I’m ashamed or displeased with the result. On the contrary, I’m very proud of it. But the making of the film was too miserable an exercise for me to gain any pleasure from looking back at the process. The American director Joe Losey once said, “Beware of a cozy British film set, because often, in the creative process, ‘niceness’ can lead to disaster.” The film of The Wall was not cozy and niceness was in short supply, but curiously we did some extremely good and original work.

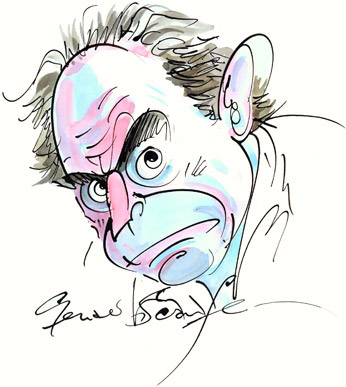

Half way through filming, the chief make-up artist Pete Frampton – quite an accomplished caricaturist – pinned a drawing of Roger Waters and Gerald Scarfe up onto the studio wall at Pinewood. It depicted Roger and Gerry as two small, scowling, grubby public schoolboys in school uniform, socks at their ankles, catapults protruding from pockets and fingers disappearing up their bogeyed noses. It was labeled “Roger, the school bully and his nasty pal Inky”.

Half way through filming, the chief make-up artist Pete Frampton – quite an accomplished caricaturist – pinned a drawing of Roger Waters and Gerald Scarfe up onto the studio wall at Pinewood. It depicted Roger and Gerry as two small, scowling, grubby public schoolboys in school uniform, socks at their ankles, catapults protruding from pockets and fingers disappearing up their bogeyed noses. It was labeled “Roger, the school bully and his nasty pal Inky”.

It was curious for us all to observe Gerry Scarfe look at the drawing, tossing his head backwards as if snorting a nostril-full of snuff, and seeing absolutely no humour whatsoever in the drawing. He had spent his life being cruel to others in his own cartoon work and probably never experienced anyone depicting him in this way. Or maybe, brilliant caricaturist that Gerry is himself, he probably thought the make-up man’s draftsmanship rather inferior.

I first came to Pink Floyd’s album The Wall as a fan. I’d been a Floyd devotee since *A Saucerful Of Secrets and over the years had played *Dark Side Of The Moon so often it ended up scratched and unplayable in its vinyl manifestation.

And as I listened to *The Wall album it was clear that it had dramatic possibilities. The whole album had a narrative sense – although, in those days, what exactly the sense was, I can’t say that I, nor anyone else, really understood. I had been in New York when the concerts were performed at the Nassau Coliseum, and I remember reading about it in the New York Times whilst filming Fame.

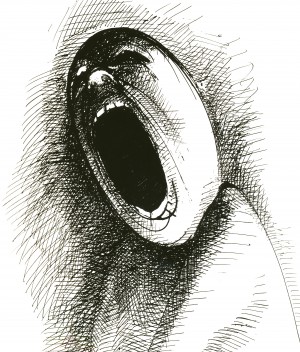

A casual telephone conversation with Bob Mercer, an executive with EMI, led to me meeting with Roger Waters, who lived nearby in Richmond. As we sat in his kitchen talking over the history of the piece, it was obvious that he wasn’t the typical zonked out rock star. He demonstrated the evolution of the work with snippets of original demo tapes. These were raw and angry – Roger’s primal scream, which to this day remains at the heart of the piece.

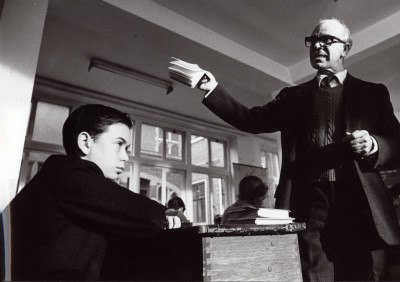

Teacher (Alex McAvoy) and Young Pink (Kevin McKeon)

He suggested that I come back the next day and meet with Gerald Scarfe, who had collaborated with him on the design of the live show. Gerry is a famous cartoonist whose drawings I’d long admired in Private Eye and The Sunday Times. When he arrived he unrolled a sort of storyboard, the size of a bed-sheet: a patchwork of his spiky drawings, somewhat sepia with age.

I still had no intention of directing the film myself. And anyway, I was more than preoccupied with my next film – Shoot The Moon with Diane Keaton and Albert Finney. In three weeks I would be leaving for San Francisco and was consequently reluctant to commit to any other project. But Roger was very persuasive and I spent the next two weeks returning each day, going through the script treatment that Roger had written.

Eventually, I left for northern California to prepare Shoot the Moon and Roger phoned me with an idea. Why didn’t I produce the film with him, with Michael Seresin (my long time cameraman whom Roger had met separately) directing in tandem with Gerald Scarfe? The idea appealed because I could be vicariously involved with a project I had great hopes for, without having to sweat the blood that directing requires. Some hope.

In January 1981 we began filming Shoot The Moon and, simultaneously, I arranged for our British production manager, Garth Thomas, to begin prepping The Wall with Production Designer Brian Morris, whom I had worked with many times before.

In the middle of filming Shoot the Moon, Pink Floyd were performing The Wall concert in Dortmund, Germany – supposedly for the last time – and so Michael Seresin and I flew on the weekend of Washington’s Birthday – a public holiday in the US – from San Francisco to Germany.

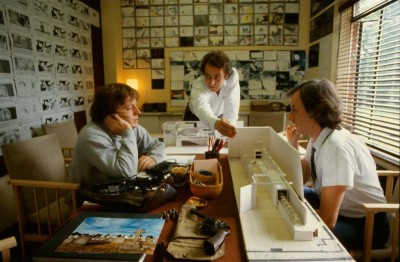

The ‘war room’: Alan Parker, Gerald Scarfe and Production Designer Brian Morris

In Dortmund, it was impossible not to be impressed by the immensity of the proceedings. The concert was rock theatre on a mammoth scale – probably more grandiose and ambitious than that genre had ever before achieved – a giant, raging Punch and Judy show. The sound was awesome, the Floyd musically precise and Roger’s primal screams, the fears of madness, oppression and alienation cutting through the cordite smoke like fingernails on a blackboard. The sheer scale of the artistic undertaking was extraordinary, not to mention the engineering problems that had been overcome to present it.

Gerald Scarfe’s animation sequence of the flowers ‘making love’. Originally made for the stage show, it’s still my personal favourite scene in the film.

Coming from the slow, almost archaic filmmaking process, to see everything – every sound fader, every hoist, effect, brick, note and light cue hit on time was impressive. The high point was the guitar solo in Comfortably Numb, with Dave Gilmour perilously perched on top of the wall, backlit, his weird shadow bleeding across the faces of the 10,000 in the audience. Also, I had a chance to see Gerald Scarfe’s animation for the first time. The copulating flowers metamorphosing from the erotic into the predatory took the audience’s breath away. The marching hammers of oppression burst across the mammoth triptych screen with three projectors synchronized with the live show sound. This created a theatrical sensation that would be hard to emulate on the movie screen. Anamorphic wide-screen Panavision and Dolby film sound suddenly seemed feeble tools in comparison to this live rock’n’roll behemoth.

Backstage it was just as impressive – no cliché rock’n’roll partying but an ultra-cool and professional atmosphere, not entirely relaxed, a little edgy in fact, but they had a job to do and the job happened to be music. Also what struck me was how everything was dominated by Roger’s autocratic, almost demonic control over the entire proceedings.

Returning to Northern California I had my doubts that the project would ever work. Roger and I had been masters of our own particular universes for far too long for either of us to kowtow to the other. It didn’t feel quite right. Steve O’Rourke, Pink Floyd’s manager, visited us in Sausalito offering unbounded enthusiasm and was to be the Henry Kissinger shuttling between Roger and myself in the year to come, trying to keep the peace.

Once the filming of Shoot the Moon was over, I returned to London to complete the editing. It had gone very well and was a relatively uncomplicated film, cutting together quite smoothly. This meant that I could spend a little more time on The Wall, the next stage of which was to work more seriously on Roger’s script.

Young Pink with his father’s cut-throat razor, East Molesey, Surrey

All photos © Tin Blue Ltd

Stills photography: David Appleby

Cinematographer: Peter Biziou

Roger, Gerald and I worked together at Gerry’s house in Chelsea and once more I would play straight man to Roger as I endeavored to push it away from the theatrical spectacle and he would articulate at great length the deeper meaning of each fleeting lyric. For Roger it was never a case of writing a script, it was about delving into his psyche to find personal truths, where I was more interested in the cinematic fiction. Gerry would quietly and unemotionally monitor these stormy ‘Special Brew’ days between Roger and myself, and when we left he would draw up the day’s thoughts into a wonderful cartoon patchwork that spread gradually across all the walls of his studio. The difficult process was to abandon the established and effective theatrical devices of the show for a more cinematic approach. But throughout, the music of the album was the touchstone for everything that we did, dictating the ebb and flow of ideas.

As the script developed it retained many of the elements of the show. One of the original intentions was to inject Pink Floyd as a band throughout the piece – to act as narrators whenever our imagery began to flag. To this end it was decided to put on five more concerts in London where the band and some of the theatrics could be filmed.

At this time, Steve O’Rourke and I returned to Los Angeles to show the new screenplay and Gerry’s brilliant but lunatic storyboard to the studios – confident that we could raise the money. It was a new experience for me and a rather depressing one. The people who had embraced me as a director, turned their backs on me as a producer. As I would describe the unusual nature of the film to the various moguls – that it was to be a fusion of different cinematic techniques, live action and animation, that it was to be a fragmented piece with no conventional dialogue to progress the narrative, music being the main driving force – they would stare back at me with total incredulity.

We had secured part of the budget from a German distributor who was an ardent Pink Floyd fan. This surprised us because movies involving World War II aren’t popular in Germany. I suppose because the good guys never win.

In Los Angeles, our problem was that no-one could comprehend that we were proposing to make something other than a concert movie, a genre that had traditionally yielded limp returns at the mainstream movie box office. The enormous success of the album (11.7 million had already been sold) was our trump card and they greedily eyed a slice of the soundtrack album, of which Pink Floyd had no intention of sharing a single cent.

Eventually MGM’s David Begelman – with whom I’d made Midnight Express, Fame and Shoot The Moon – shook on a deal. He said, “Alan, I don’t understand this movie. No one in this company understands this movie. Even my 19-year-old son doesn’t understand this movie and he’s a big Pink Floyd fan. Are you sure you can pull this off?” “Quite sure,” was my answer. “Don’t worry, we won’t let you down, David. You know we’re very responsible – we always treat other people’s money as if it’s our own.”

I bit my lip as I uttered the last dumb line. Begelman had famously embezzled money from Columbia before landing the top MGM job and was therefore familiar with treating other people’s money as if it was his own. He was also a compulsive gambler – regularly losing $100,000 dollars at his weekly Hollywood card school. It’s not surprising that he was the only one in Hollywood mad enough to take a punt on us.

Back in England, the concerts were put on at Earls Court in June and over five nights we set about with multiple camera crews ready to capture the necessary footage. The filming was a total disaster. Michael and Gerry didn’t gel as directors, or even realize what exactly they should be doing. As for myself, I was quite useless as an impotent director and even less useful as an impostor producer and began chain smoking for the first time in my life.

Bob Geldof drowning in a swimming pool of blood. This came easy to Bob, as he wasn’t much of a swimmer.

From the start, the dilemma was that the needs of the film compromised the show. The concert, better organized and ticking along as it always did, could not be spoiled by the requirements of the film crews, most of them befuddled and rudderless – completely in the dark in more ways than one (the fast Panavision lenses needed had no resolution and so the resultant rushes looked like they had been shot through soup). As I sat alone in the backstage area among the curious plastic chairs, picnic umbrellas and Astroturf it was clear that we couldn’t go on like this. Either we abandoned the film, or I had to come out of the producer’s closet and start directing proper. Roger and the band had also come to the same conclusions.

There were a number of obstacles to me taking over. Firstly, Michael Seresin, a good friend, who’d worked as my cinematographer on many of my films was obviously disappointed at being demoted and, not unsurprisingly, he withdrew. Gerry Scarfe had his animation to get on with and acquiesced more easily if not without some resentment.

For myself it was a case of being back to square one. Roger was a formidable challenge. His personality and grasp of the material were intimidating for anyone who dared to creatively purloin it. But even Roger wanted me to direct, wary as he was of my ‘final cut’. We were both obdurate to a fault. Or as my longtime producer Alan Marshall eloquently put it: “Two egotistical, opinionated fuck-pigs who think they run the show when in actual fact it’s everyone else who does the work”.

My main provisos were, firstly, that Roger should step back a bit to give me air, and secondly for Alan Marshall to take the producer’s role that Roger and I were only half-accomplishing. Conveniently, the six weeks of preparation prior to filming coincided with Roger’s summer holiday, so I got my space after all.

This was the most valuable time for me as I took the sparse blueprint of our ‘script’ and began to formulate the images that could accompany the music. Meanwhile Gerry Scarfe had begun new animations, including a maze and a human mincer for Another Brick In The Wall Part 2, while Brian Morris set about translating these drawings into mammoth sets.

The concert fiasco had provided us with an unexpected bonus in that it proved the ‘band as narrator’ idea was not only naff, but superfluous. It was clear that the film was evolving as anything but a concert film and so we had to avoid seeing the band.

My priority at this time was casting. Our main character, Pink, had to be found and I trod the well-worn route of British and US film actors. I also thought we should look at some other rock artists – not easily sold to Roger as we had all agreed that he shouldn’t play the part himself, his skills being closer to those of Albert Speer than Albert Finney.

Bob Geldof was suggested. I had liked his performance in a video the Boomtown Rats had done for “I Don’t Like Mondays”. We met and I asked him if he’d seen The Wall. “Yes, I’ve got one at the bottom of my garden,” he answered. Bob wasn’t a big Pink Floyd fan but the notion of “posing on cue”, as he put it, rather appealed to him. We did a screen test at Shepperton where he read Brad Davis’s courtroom speech from Midnight Express. He did it wonderfully, surprising us all with his control. Being a non-swimmer Bob’s biggest fear was the swimming pool scenes and he spent two weeks at Clapham Baths perfecting a passable dog paddle.

For the rest of the cast I relied very much on actors who had worked with me before. I was particularly happy to get Bob Hoskins to play the manager and for the hotel room scene I wrote dialogue for him to work with, but he soon abandoned it and improvised on his own, giving the crew rare laughs that were noticeably absent from the rest of the filming.

We began filming on September 7, 1981 at a retired admiral’s house in East Molesey. The recently deceased occupant hadn’t decorated for many years allowing us to swiftly turn back the clock to the 1950s. From the start I had asked everyone to be brave, and for the sequence of the teacher and his wife eating their gristle dinner the cinematographer, Peter Biziou, lit the interiors with an enormous ‘brute’ light at floor level. With the unusually harsh light, you could see the pores on their faces. And so a pattern was set for the rest of the filming.

Meanwhile, out in the garden, the second unit had the thankless task of working with six cats and three crates of doves, in a vain attempt to capture a single shot of a dove soaring into the sky. We lost fifty doves and twenty pigeons before we grabbed the few necessary frames of the fluttering of wings.

It wasn’t a conventional screenplay, not shot by shot or storyboard image by storyboard image; sometimes we had five lines of description to go on and some days we had a great coloured painting by Gerry to set us off on a chaotic, anarchic journey in search of a film. The recurring dream of Pink’s childhood – always the journey never the destination, life as constant delirium as he runs interminably across the rugby field, was filmed on Epson Downs. I’d seen a dozen different rugby pitches but none gave us the eerie dream quality that we were after. Eventually I decided to erect our own posts on a perfect spot on Epsom Downs, with the early morning sun bleeding across the field as Pink runs towards us.

It wasn’t a conventional screenplay, not shot by shot or storyboard image by storyboard image; sometimes we had five lines of description to go on and some days we had a great coloured painting by Gerry to set us off on a chaotic, anarchic journey in search of a film. The recurring dream of Pink’s childhood – always the journey never the destination, life as constant delirium as he runs interminably across the rugby field, was filmed on Epson Downs. I’d seen a dozen different rugby pitches but none gave us the eerie dream quality that we were after. Eventually I decided to erect our own posts on a perfect spot on Epsom Downs, with the early morning sun bleeding across the field as Pink runs towards us.

The World War II sequences had been streamlined to a practical size by the time we dug in and transformed Burnham-On-Sea in Somerset into the Anzio bridgehead, complete with barrage balloons, bunkers and Italian gun emplacements. Our “soldiers” were enlisted from the local Labour Exchange and performed like regular troops in the battle scenes for In The Flesh? and the aftermath that begins The Thin Ice. There were a few complaints in the trench scenes when I introduced live rats amongst the piled up soldiers, but a strike by the extras was averted when an additional fee was negotiated with the promise that only non-biting, tame rats would be used. For some reason, they fell for that one.

Meanwhile our model Stuka planes were put into the air – the first of which unceremoniously nose-dived into the sand before we could even turn on the cameras. The second plane had a similarly brief lease on life, but gave us the shot we needed before it disintegrated in mid air.

Geldof had his first taste of filming sitting in a chair in this alien landscape. As he choked on our smoke machines and did more shivering than acting, he suddenly realized that it was a long way from the ‘posing on cue’ that he had envisioned.

I don’t think I tried anything on The Wall I hadn’t tried before, but I certainly tried *everything I’d tried before. As a location for Pink’s drift into his memory and madness, we had built an enormous composite set of his LA hotel penthouse suite at Pinewood and used a special inclining prism on the lens of the Panaflex camera to allow us to film from floor level to capture our distorted view of Pink. I borrowed from Abel Gance and suspended the camera on a pendulum to film Geldof thrashing around in the imagined pool of blood as Pink recalls his father’s death. Bob floated in the scarlet syrup, the camera slowly zooming out to a position, suspended upside down in the studio rafters. Destroying the hotel room took no time at all. Bob launched himself, as usual, into each take with equal ferocity, cutting his hands quite badly each time until there was little left to break and we stopped to patch him up before he lost too much blood.

I don’t think I tried anything on The Wall I hadn’t tried before, but I certainly tried *everything I’d tried before. As a location for Pink’s drift into his memory and madness, we had built an enormous composite set of his LA hotel penthouse suite at Pinewood and used a special inclining prism on the lens of the Panaflex camera to allow us to film from floor level to capture our distorted view of Pink. I borrowed from Abel Gance and suspended the camera on a pendulum to film Geldof thrashing around in the imagined pool of blood as Pink recalls his father’s death. Bob floated in the scarlet syrup, the camera slowly zooming out to a position, suspended upside down in the studio rafters. Destroying the hotel room took no time at all. Bob launched himself, as usual, into each take with equal ferocity, cutting his hands quite badly each time until there was little left to break and we stopped to patch him up before he lost too much blood.

The scenes of Pink’s wife, played by Eleanor David, and her lover were shot on location at a Kensington house. Sex scenes are always difficult to pull off and your first job as a director is to relax the actors, who in this case appeared to be more relaxed than I was. James Hazeldine, who was playing the lover, arrived early, and I sent him off to the pub across the street for a ‘stiffener’. Only the camera operator, focus puller, and myself were going to be there while we shot the scenes and we moved the speakers close to the bed, pumping up the volume of the playback tapes to maximum. As the three of us encircled James and Eleanor — we were paid voyeurs with a Panaflex camera – the 40 crew crowded in the room next door must have wondered what the hell was happening as they heard the residual grunts and groans when the music stopped.

Then we moved on to what we feared would be our most difficult shoot: the Nuremberg-style rally we’d conceived for In The Flesh. Location-wise, we’d settled for the reality of the Royal Horticultural Halls in Westminster, with a specially built stage and a thousand flags bearing Scarfe’s crossed hammer symbol. Our problem was the skinheads. How could we make them behave in a civilized and safe manner? Stop them from being bored; stop them from kicking everybody’s heads in?

The toughest section of the skinhead crowd was a group called the Tilbury Skins from South East London. We had partially diffused the threat of real violence by elevating this group to a more prestigious position in the film as Pink’s ‘Hammer Guard’ and we were going to use this bunch of mostly amiable loonies as the nucleus of the violence that was to follow. Our stunt co-ordinator had been working with the skins for a month previously at Pinewood, showing them the rudiments of film stunting and the way to kick someone in the face without breaking their nose and jaw.

Slowly we superimposed a sort of disciplined logic onto their violent behaviour – well sort of. I remember the crowd reactions as Geldof first made his entry for In The Flesh and then proceeded to sing the odious lyrics. The sheer spectacle of the proceedings was very seductive and I can remember my fears that some in the audience were taking the diseased and demented Pink rather too seriously.

Riot: Police lines, Beckton Gasworks, Kensal Rise, London

When you’re making a film, it’s pieced together like a giant Lego set, shot by shot, decision by decision — a thousand decisions a day – and then you eventually see the cumulative effect this has on an audience. Only then do you realize the power you wield. The most alarming feeling was in a pub at lunchtime, when our jackbooted guards in full uniform walked in and ordered their pints. The local residents, unaware that it was a film, drank up and promptly shuffled off, believing these shaven-headed, Nazi-uniformed gentlemen were for real.

So violence the skins could do, but how would they feel about *dancing? For Run Like Hell our choreographer, Gillian Gregory, who had worked with me on Bugsy Malone, had devised a Nazi-like disco routine. She had spent the morning rehearsing the crowd in batches of a hundred in the car park opposite, and had whipped them into passable shape. I remember my conflicting feelings as the assembled skinheads dutifully performed their fascist frug to the play-back tapes – acting as one in an unthinking, programmed, mechanical mass. On stage, Bob goaded them into action with his crossed arms hammer salute and they followed with a zombie-like precision, no doubt perfected on the terraces of Millwall Football Club.

So far, so arduous. We’d tangled with rats and cats, destroyed Stukas, wrangled skinheads, and borrowed a special camera lens off a group of research biologists in Oxford (for the shot at the beginning that moves from Pink’s Mickey Mouse watch to the centre of his eye) but I’d stayed on the right side of Roger and failed to kill Bob. Or that was the case until we shot the “asylum” scene.

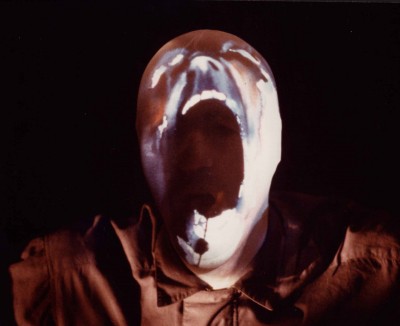

In a very early script Roger had alluded to a bald-headed loony munching sweets in a padded cell. This fear of impending madness – probably Roger’s fear of becoming Syd Barrett – were images that I wanted to develop and which Roger had wished he’d never mentioned. Especially the bald-headed loony.

At a disused cake factory in Hammersmith, we had converted a dilapidated, damp-walled warehouse into a surreal mental ward. Up to now I had near asphyxiated Bob with toxic smoke, shaved off his eyebrows with an open razorblade, nearly drowned him in a swimming pool full of blood, cut his hands to shreds destroying the hotel room — all without complaint. However, the application of the viscous pink make-up was dreadfully uncomfortable for Bob and so, for the first time on the film, he rebelled. As he was dragged down the iron fire escape in the bitterly cold air, clothed in the remnants of his underpants and a bucket of pink gunk, he was heard to shout, “Parker’s gone too fucking far! I will not be physically abused!”

Back at Pinewood, Brian Morris had finished our biggest set; the school maze and human mincer complex for “Brick 2”. We had drilled the kids into regimented automatons, the pink masks wiping out their personalities as they are processed through the production line of a blinkered educational system.

I always thought it ironic that the mesmeric chorus in Another Brick In The Wall Part 2 was recorded by pupils at Islington Green Secondary School, whose subsequent claim to fame was as the school Tony Blair refused to send his children to. The school has one of the highest truancy rates in Britain, which is probably why so many of them turned up for the original recording.

The destruction that accompanies the guitar solo began in the studio, where the sets were demolished for real by our eager young actors, and continued at Beckton Gasworks where a derelict Victorian building was carefully set on fire by the Special FX department – eyed nervously by the local Fire Brigade. The result is one of the more disturbing moments in the film: Pink’s murky surreal daydream, as he is bullied by the Teacher for writing poetry. “Absolute rubbish, laddie,” scolds Teach as he reads aloud the childish rhyme – actually the lyrics of *Dark Side’s Money, a lame joke of mine at Roger’s expense and consequently of little amusement to him.

We were now into the final week of filming but no nearer a conventional “conclusion”. Months before, we’d written in the script a phrase which read, “We cut to the Broader Issues”. It was a reminder to underline our overarching theme: the walls and barriers that are erected in society resulting in our alienation from one another. It was nebulous, but it was all we had.

Consequently, on day 57, the call sheet read, “Exterior. Night. Broader Issues: 150 rioters and police; stunts; police riot equipment; police vans, cars, motorcycles; FX fire, smoke and explosions; tear gas guns.” Quite what I was going to do with this assemblage, I wouldn’t know until the night.

We were in Beckton again, where the decaying skeleton of the gasworks complex had become our inner-city film studio. Many years later Stanley Kubrick shot much of Full Metal Jacket there, but in 1981 the industrial waste was still in evidence and the crew were demanding ‘dirty money’ for working in the rain, ankle deep in years of coal dust and silicosis. On top of those problems, the only riot image I’d pre-conceived was the ‘wall’ of police, their shields glinting in the flames. As the night drew on and the skinheads and ‘police’ clashed for the dozenth time, tempers rose. However many times we reminded them that this was a make-believe riot, the fighting always seemed to continue long after I had yelled ‘cut’.

Ultimately, the violent scenes in Run Like Hell were probably the ugliest we shot. The café set we’d built behind Kings Cross railway station was completely destroyed by the Tilbury Skins, who couldn’t believe their luck. The rape scene was the most repugnant of all, and any amount of professionalism on behalf of the crew can never detract from the vicarious involvement you have as filmmakers.

The main shoot was completed after 61 consecutive fourteen-hour days consisting of 977 shots, 4,885 takes and 350,000 feet of film. After 16 weeks of us running free Roger returned to reclaim his baby and I received a stark reminder of the realities of the collaborative process.

Roger and I collided one day in the dubbing theatre both vomiting venom, like the Judge in the animation sequence. Curiously our arm wrestling was rarely about creative matters. Our problems were more about creative authorship than creative differences. Fortunately, my editor Gerry Hambling had little patience for puerile squabbling. He continued to astound us all as he fashioned, with scalpel and meat cleaver, my live action, and nipped and tucked at the animation to make it work with the music.

Our editing staff grew ever bigger as tracks were laid and opticals prepared in our attempt to meet our proposed Cannes Festival deadline. Meanwhile at Pinewood Theatre 2 Dubbing Theatre, James Guthrie, the engineer of the original album, was pre-mixing the music tracks. He was keen not to miss too many generations of sound and would be mixing onto film directly from the original recorded masters. To this end a truckload of additional equipment arrived (including three linked-up 24-track desks), until the place resembled a Boeing 747 ripped apart for an overhaul.

Our editing staff grew ever bigger as tracks were laid and opticals prepared in our attempt to meet our proposed Cannes Festival deadline. Meanwhile at Pinewood Theatre 2 Dubbing Theatre, James Guthrie, the engineer of the original album, was pre-mixing the music tracks. He was keen not to miss too many generations of sound and would be mixing onto film directly from the original recorded masters. To this end a truckload of additional equipment arrived (including three linked-up 24-track desks), until the place resembled a Boeing 747 ripped apart for an overhaul.

There was also music to produce. The Tigers Broke Free had yet to be recorded and Roger set about the task with Michael Kamen, who had written orchestral arrangements on the original album. There were new versions of Mother and In The Flesh, Outside The Wall was completely reworked with a brass band (technically a ‘silver band’) while Bring The Boys Back Home gained a full orchestra and the Pontardulais Welsh Male Voice Choir.

The animation studio now moved down to Pinewood and an artists’ sweat-shop was set up in the old gatehouse overseen by Gerry Scarfe and the principal animator, Mike Stuart. They had been working for well over a year on the seven minutes of new animation and perfecting the cells from the existing concert footage, adding up to 15 minutes of animation in the finished film. It was a bewildering time for Gerry amidst the cut and thrust of movies, distant as he was from the cozy environment of his Chelsea studio and the solitary artist’s life, but he continued to turn up.

The animation studio now moved down to Pinewood and an artists’ sweat-shop was set up in the old gatehouse overseen by Gerry Scarfe and the principal animator, Mike Stuart. They had been working for well over a year on the seven minutes of new animation and perfecting the cells from the existing concert footage, adding up to 15 minutes of animation in the finished film. It was a bewildering time for Gerry amidst the cut and thrust of movies, distant as he was from the cozy environment of his Chelsea studio and the solitary artist’s life, but he continued to turn up.

The dub is always the most rewarding part of the film, when all the elements come together for the first time. It’s also, on a normal film, the most comfortable time, away from the insane ‘controlled chaos’ of a film set. Much to everyone’s surprise, it was a smooth and civil process and the most amiably co-operative time between Roger and myself. He was very keen to join Guthrie and the other mixers on the sound desk, allowing him the tactile pleasure of once again being back in touch with his original creation.

After eight months of editing we had arrived at our final cut. We’d shot 60 hours of film which was whittled down to 99 minutes of screen time and Gerry Hambling had made 5,400 cuts. The animation artists had done over 10,000 full colour paintings to complete their 15 minutes of screen time. When we began, in my customary letter to the crew, I had likened the upcoming film to Livingstone going up the Zambezi. Now that it was finished, it felt more like going over Victoria Falls in a barrel.

Afterwards

On reflection, Pink Floyd The Wall was quite the most miserable time I ever had making a film. It’s a scream of pain from beginning to end. But sometimes out of conflict comes interesting work. I never had the advantage of going to film school, so this is probably my student film – the most expensive student film in history. In a way, it’s an experiment in cinematic language. The parameters were never set and, budget constraints apart, no limits imposed — all of which was creatively liberating. It was like the image of Geldof lying amongst the debris of his trashed room: the pieces put back together to create a weird and wonderful work of art.

Because of the continued success of the album, the film also endures, having become a cult hit of the genre. But when it came out it wasn’t even reviewed by film critics, probably under the misapprehension that it was a rock’n’roll concert film. The band’s insistence that Pink Floyd’s name stay in the title didn’t help. At the time, most film critics were of a certain age and had little relationship with rock music.

For all the misery that the film conjures up for me I am still very proud of it. It predated the popularity of the music promo and was a brave, original, if somewhat lunatic, endeavour. Anyway, I wish I had a dollar for every shot I’ve seen copied on MTV.

When it was finished, it was duly shown at the Cannes Festival where we were one of the last films to be screened in the old Palais. To make sure it sounded as it should – uncompromised by the then feeble, film festival sound – two truckloads of Pink Floyd PA were driven to the South of France, and when the music hit full throttle the whole building began to shake — large flakes of paint drifted down from the Palais ceiling, covering the audience with giant dandruff. It was a magnificent experience, much appreciated by the audience. Stephen Spielberg stood up at the end and politely bowed towards me. He then shrugged to his neighbour, Warner Brothers studio head Terry Semel, apparently saying, “What the fuck was that?”

After the openings of the film, I never ever saw Roger Waters again. The album cover of the next Floyd album portrayed a tall gentleman in World War II British army officer’s uniform holding a film can and with a large knife in his back. The album was called *The Final Cut. Waters left the group soon after. I remain friends with Pink Floyd’s Dave Gilmour and Nick Mason, but whenever I’ve had occasion to bump into Gerald Scarfe (he lives near me in London) he shudders and avoids me. He’s an odd one is Roger’s pal Inky.

Steve O’Rourke, Pink Floyd’s longtime manager and the glue that held this film together, was chatting up my assistant Angie one day in our bungalow in the Pinewood gardens when he received an important phone call back at his office in the main block. He charged back and, being dreadfully myopic, he ploughed through the closed plate-glass doors, shattering them and filling his face with arrows of glass. Angie bent over him and lovingly plucked the bloody shards from his face, leading to the only nice thing that came out of the movie of Pink Floyd The Wall: they fell in love and got married. Sadly Steve died in November, 2003 and his coffin was sent off to the sound of the band playing The Great Gig In The Sky.

David Begelman, the boss of MGM, was the only person in Hollywood we could persuade to make this film. When I showed him the completed film he confessed that he found it disturbing and particularly asked me to take out a shot of maggots consuming a lamb’s brain. On August 8, 1995, plagued by his own personal demons, he checked into the Century Plaza Hotel and in corner king room 1081, took out a .38 pistol and blew his brains out.

*The Wall album went on to sell 23 million (plus) copies, becoming the third biggest-selling album in history.

Originally published as production notes and this version by Mojo Magazine, Jan 2010

After, Afterwards

After, Afterwards

The success of the album continues as new generations discover it. Roger still performs and tours his own personal version of the stage show, updated as it is with digital brilliance and session musicians. Roger even invited me to see the show at the O2 arena, and was most welcoming. Gerald Scarfe also made his peace with me. When he was preparing his own book on his personal journey with ‘Pink Floyd on The Wall’.

I was not overly surprised to read that he had an equally torrid time on the movie as myself. He wrote, on dealing with me, “One morning I drove to Pinewood studios with a bottle of Jack Daniels on the seat. I knew what was coming and had to have a slug before I went in.”

Didn’t we all.

All text © Alan Parker. All photos © Tin Blue Ltd. Stills photography: David Appleby. Cinematographer: Peter Biziou