THE MAKING OF MIDNIGHT EXPRESS

A personal memoir by the director, Alan Parker

Written to accompany the 25th anniversary edition of the DVD.

The above says ‘personal memoir, because when it was originally written it was heavily censored by a lawyer in Sony’s legal department on the grounds that my view of the making of the film was not that of Sony. I pointed out that the lawyer was not there in Malta when we made the film, indeed, neither was Sony, who bought Columbia ten years after our film was made. Common sense prevailed and they relented, allowing it to be released as my ‘personal memoir’.

I had originally been invited to New York in the winter of 1976, to see the stage version of The Wizard of Oz, The Wiz, which Universal wanted to make into a movie. I wasn’t mad about the show and, after a nice lunch with the studio executives, I politely passed on the project. Walking along Fifth Avenue on the way back to my hotel, I bumped into Peter Guber, who was coming out of the Columbia building. I had met Peter a few times before with David Puttnam, who always likened fast talking Guber to the character of ‘Fat Sam’ in my film Bugsy Malone. Peter said he had a manuscript of a book that he would like me to read and he went back into the building to retrieve a copy of the galleys of Midnight Express, which I dutifully read on the plane back to London.

Guber had been involved with the William Hoffer ghosted book ever since the Billy Hayes story had been serialized in Newsday magazine, soon after Hayes had escaped from prison. Simultaneous to my fortuitous sidewalk meeting with Guber (and completely unrelated), my friend David Puttnam (and the executive producer of Bugsy Malone) had been in discussions for some time with Guber to become a partner in his new company, Casablanca Filmworks. As their first project together would be Midnight Express, I agreed to take on the film, along with my long-time producing partner from commercials and Bugsy Malone, Alan Marshall, who would produce with David Puttnam with Guber riding shotgun in L.A. as Executive Producer.

Producers, David Puttnam and Alan Marshall

In Los Angeles, Guber introduced me to a young writer he had found called Oliver Stone. Oliver had no screen credits at the time, but had written a number of excellent unmade screenplays. Guber sent me one of them, which was based on Oliver’s own Vietnam experiences. It was an outstanding piece of film writing even though, at the time, no one wanted to make it as a film. Up to this point, I had always written my own screenplays, so the experience was new to me.

Oliver and I had lunch at a deli on Wilshire Boulevard and the pattern was set for our future relationship. Sample conversation: “I think the father is very important, I liked him.” “ You did? I disliked the father intensely.” Or, “I think this is phony.” “Really? I think it‘s very real.” “I believe this is genuine.” “No, it’s B.S.” “I think he’s a victim.” “No, he’s a creep.” “At this moment, you should feel pain.” “No, at this moment you feel euphoria.” “I think it’s black”. “No, it’s white.” (It doesn’t matter who said what, I think you get the general idea.) I had the feeling that he was bemused that I had got the gig in the first place. After all, he reasoned, why would someone who had made Bugsy Malone, with kids and custard pies as their first film, be interested in the Midnight Express subject matter? Truth was, that it was much closer to the kind of films I wanted to make than the pragmatically conceived Bugsy.

It was agreed that Oliver would come to London and begin work on a script based on the William Hoffer book. A month later (early 1977), he was ensconced in the back room of the offices of Alan Marshall and my TV commercials company on Great Marlborough Street, in Soho. Oliver thought the offices were oddly ‘Dickensian’ and appeared to dislike all things English, including us. However, regardless of the personal and cultural divide, day after day, Oliver assiduously pecked away at his typewriter. It is fair to say that, despite the vim of Oliver’s backroom keyboard tappings, neither Puttnam, Marshall nor myself was overly optimistic as to what the outcome would be. Even though he wrote the script fifteen feet from my office, I can’t say, at that point, that I’d made much of a contribution, outside of helping with the Max (John Hurt) character — as Oliver admitted to not understanding or liking Englishmen (a notion with which we could all concur.)

Six weeks later, in early April of 1977, Oliver emerged from his smoky room announcing that he had finished the first draft. The resultant beaming smiles from Alan Marshall and me were probably less to with the anticipated first draft script than the imminent departure of the tenant in our back office.

Oliver instructed his agents in London, William Morris, to print up the script and simultaneously deliver a copy to Puttnam, Alan Marshall and myself. Oliver promptly, if not purposefully, disappeared on vacation to places unknown, not aware (or probably caring) of our reactions. The three of us read the script immediately, frankly expecting the worst. To all of our surprise, the first draft wasn’t bad at all — in fact, it was brilliant. Whatever my personal feelings about Oliver, they soon became instantly irrelevant because of the quality and energy of his first draft screenplay. It was edgy, uncompromising, succinct, full of rage and with a cinematic energy that tore through the pages like an express train from hell. None of us had ever read a screenplay like it.

Our next priorities were casting and finding a location in which to set our Sagmalcilar Prison. The production had been given strong advice not to risk the dangers of shooting in Turkey and so we embarked on a location hunt in a half-dozen countries in Europe. We had zeroed in more thoroughly on Italy, Greece and Spain, but nothing seemed to be either close enough to the original Turkish prisons, or special enough to enable us to create our cinematic vision.

Alan Marshall and I had visited Turkey with some trepidation for our first scout. We felt like pathetic, clandestine spies as we followed the route mapped out by Billy Hayes’s journeys in Turkey. Oliver Stone’s first draft screenplay had followed pretty accurately, in structure at least, the Billy Hayes/William Hoffer book. Principally, the story called for more than one prison. The first draft screenplay had Billy leaving Sagmalcilar for the island prison of Imrali from which he escapes, as per the recounting of Billy Hayes’s actual story. I have to say, for whatever reason, we were somewhat nervous and fearful whilst looking for the original locations in Istanbul. We had been advised to be cautious on our visit and to be careful of photographing anything sensitive. We told anyone who asked that we were scouting for a Benson and Hedges commercial and I had even written a ‘cod’ script to hand out in case we were stopped for questioning.

Istanbul was shoddy, dilapidated and filthy when we visited, at odds with the pictures in the holiday brochures. We visited Sagmalcilar prison in the smoke filled, shabby, pot-holed industrial outskirts. Architecturally dull at first sight, I tried to take photographs but there were far too many police around and so I hurriedly started to sketch everything of interest. We visited the dismal prison for the mentally insane at Bakiroy (cozily called The Bakiroy Hospital for Mental and Nerve Illnesses) and many of the observations we made there added to the textures of the resultant film. Similarly I scribbled drawings and made notes of ‘The Pudding Shop’ in Sultanahmet near the fabled Blue Mosque. The original script had called for a chase on the Turkey/Greece border and we endeavored to recce there, but were turned around by tanks and soldiers who smiled as they waved our rental car back to Istanbul. My detailed drawings of the airport would certainly get me arrested these days.

Back in Los Angeles, I began casting. The film was to be made under Peter Guber’s Casablanca Filmworks deal with Columbia and so there was little pressure on casting stars as long as the budget remained at the low end of the scale —ironically what now would be called an “indie film”, but then made by a major studio. (The film’s final budget was $2.7 million. Or as Peter Guber is fond of saying, “the whole of the budget of Midnight Express was the catering bill of most films today.”)

David Puttnam was firmly ensconced in his executive job at Casablanca and so was never far away for advice and encouragement as I began casting in the spring of 1977. The casting director was Penny Perry. The studio was passively involved, with a few suggestions of actors, but basically they left us to it.

The studio was keen on a hot young actor called Richard Gere, who had been talked about after Looking for Mr. Goodbar by Richard Brooks, starring Diane Keaton and Bloodbrothers by Richard Mulligan. Terrence Malick had more recently directed him in Days of Heaven and Malick was asked if he would show me some footage from his new film. Famously guarded about his work, in his editing rooms in West Hollywood, he reluctantly ushered me towards a clattering Moviola and I watched about two minutes of dailies: namely, Brooke Adams and Gere eating an ice cream. Frankly, it was not the stuff that makes you punch the air with, “Yippee, Eureka”. “Is there anything else I could see?” I asked, shyly. “Nope,” said Malick, shaking his head. I thanked him and left.

I met with Richard Gere a couple of times. He was obviously the front-runner, but he refused to ‘read’ for me (i.e. read through scenes in the script, as in an audition, in order for me to appraise his suitability). He said he disliked ‘cold readings’ and, although still quite inexperienced, thought that he had achieved sufficient ‘status’ so as not to endure this traditional process for young actors. Consequently a commitment was slow in coming from both directions.

I continued with the American side of the casting process in New York and Los Angeles. One day, David Puttnam left early for lunch and he magnanimously suggested that I continue casting in his rather sumptuous office instead of the broom cupboard I had been allocated. An actor called Bud Cort (Harold and Maude) came in. I sat across from him at David Puttnam’s elegant oak desk. In the light of the seriously expensive, art deco desk lamp, Cort said, “Would you mind if I humiliate myself?” “Humiliate yourself?” I replied, somewhat puzzled. “Yes, the character in the story is humiliated at various points and so I feel like I should humiliate myself to get into the role.” “Fine,” I said, not really knowing what he was talking about. I had only been in Hollywood for two weeks and wasn’t going to let on that I knew absolutely nothing about the often eccentric, casting process. Gullibly, I took everything as it came at me. The actor proceeded to take off all his clothes and stand completely naked in front of me. I averted my eyes, staring down at my script for a good few minutes, “OK,” I said, tapping my pencil as if this happened all the time. “Would you like to read the scene? From top of page 78, I’ll read Stanley Daniels.”

“Can you wear my shirt while I do this?” he said, “It will help.”

“Sure, why not,” I said, now complicit in his ‘method’, as I dutifully buttoned his denim shirt over mine. He then read the scene, which involved Billy grabbing his lawyer by the lapels after learning that his four-year drug possession sentence had been transmuted to life imprisonment. His wonderfully zealous acting took hold, mostly of me, as he lunged forward, ripping the denim shirt in the process. Screaming at the top of his lungs, he tipped over Puttnam’s oak desk, the personal knick-knacks and papers crashing to the floor, and smashing the seriously expensive art deco lamp into a thousand pieces. I sat there amongst the wreckage pretending to be non-plussed and professional. Puttnam’s secretary, Linda Smith, came rushing in and gasped at the debris and myself smiling stoically and complicitly, still dressed in Bud Cort’s ripped denim shirt. “Is everything OK? she asked. “Fine, perfectly fine,” I answered, turning to Bud. “Shall we run that through one more time?”

John Hurt (Max) and Paul Smith (Hamidou)

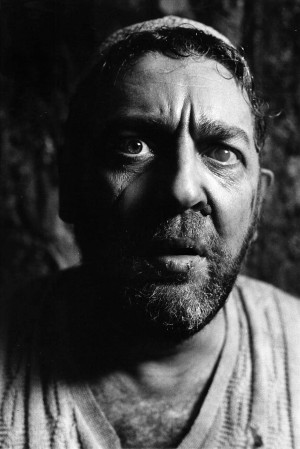

In London, I had met with John Hurt, who we had wanted for the Max character. He had most recently been enormously successful playing Quentin Crisp in The Naked Civil Servant. He came in with a complete sketch he’d drawn of his idea of Max, replete with wispy beard, right down to the Scotch-tape on his broken spectacles, and that’s pretty well how he looked in the film. Working with John was a director’s dream and he was subsequently rewarded with an Academy Award® nomination.

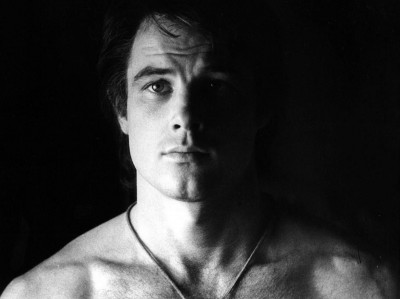

In Los Angeles after a long day of casting, I sat contemplating my notes and a sea of Polaroids, when a harassed, flushed-faced young man poked his head around the door. He said he was Brad Davis and apologized for being two hours late and filthy — his hands and face were covered in grease. His VW had broken down on the way from his home in North Hollywood and he had eventually abandoned his car and ran five miles for the interview. I read with him and was very impressed. He was desperate to play the part — so fragile and vulnerable and with a pent-up, frustrated rage and so much spare energy that he scarcely knew what to do with. He had recently gathered good notices for his part in the TV epic, Roots where he played Old George, the white man who befriends the black slaves. It’s fair to say that at the time Brad wasn’t at the forefront of anyone’s lists for casting. As he said afterwards, “You couldn’t give me away with gift coupons, at that point in my career when Alan cast me.”

Our location hunt had zeroed in on the island of Malta in the Mediterranean. There we found a disused army fort, St. Elmo, built by the British as a garrison in the 19th century. It was now completely empty, crumbling and, to our eyes at least, a very desirable film studio. What the fort didn’t have was a big enough room in which to situate the main ‘kogus’ set where many of our scenes were played out. Geoffrey Kirkland, the production designer, and I decided to build this structure tucked into the corner of the existing courtyard and made from the same dusty, honey-colored limestone blocks as the rest of the fort.

Oliver Stone had written a second draft of the script in Los Angeles incorporating everyone’s notes. The big differences from the first draft were the conflation of prisons. It was felt that by transferring to an island prison halfway through the story, the lid was somewhat lifted off the pressure cooker — too much lapping water and blue sky. Also important was that established characters like Max and Hamidou were suddenly not there in our story anymore. It was therefore decided to discard the island prison and keep everything focused in one place so that when Billy bites out the tongue of the venal trustee, Rifki, he is subsequently transferred to Section 13 for the criminally insane: an annex of the same prison.

Oliver delivered his draft and the next time I saw him was at the Golden Globes a year and a half later, where the film was fortunate enough to win six awards including Best Screenplay for Oliver.

Puttnam and Guber continued to play defense with Columbia. Daniel Melnick was the head of production at the studio and a big supporter of the film. However, he had a big problem with the scenes of apparent homosexuality in the showers that Oliver had written. Descriptions like, ‘probing one another’s bodies’ had alarmed the conservative sensibilities of the studio. Puttnam and I fought Melnick to keep these scenes of tenderness in the script, but I did agree to limit how far they would go, otherwise Melnick was ready to cut them completely.

Richard Gere did finally agree to “read” for me, but probably to make his point about ‘cold readings’ did so in a very perfunctory manner. Great actor that he is, he still read the words as if they were the Yellow Pages, not next year’s Academy Award-winning screenplay. But he did sort of agree to do the film — albeit, somewhat tentatively. At Puttnam’s suggestion, for safety, we had simultaneously embarked on screen tests with a number of other young actors including an ‘all stops out’, impassioned performance of the courtroom monologue by Brad Davis and also one by a very new in town, young Dennis Quaid, whose older brother Randy had already been cast in the film. Many years later, when I worked with Dennis Quaid on Come see the Paradise, I presented Dennis with a small film can containing his Midnight Express screen test.

Paolo Bonacelli, Rifki

I had also decided to extend the casting net to London, Athens and Rome for the other parts. I was not allowed to cast in Turkey and so in London I read every Turkish Cypriot actor (and cook and waiter) and a few Armenians. In Athens, I filled a couple of smaller parts as well as in Rome, including the very excellent Paolo Bonacelli, who played the duplicitous ‘trusty’ Rifki. It was while I was in Rome that I got the call from Puttnam that Richard Gere had pulled out. I think it was a relief to all of us because he had never really been totally enthusiastic about what we were doing. I immediately said, “Fine, let’s go with Brad,” I put the phone down knowing that Brad would give his all for the film —his subsequent performance would become the performance of his career. The studio did not share Puttnam and my enthusiasm for Brad. Indeed, the studio executives were convinced he was ‘cross-eyed’ and not a movie star. Or, as Peter Guber has said, in his colorful style, “Once you’re on the river and the rapids are ahead and you can’t get to shore, you’re best to give the crew it’s due and try and make it through. At that point the momentum had been achieved by the picture and the director and we thought that we’d rolled the dice this far, and so we’d better support them.” I think that meant he agreed with us.

For the main antagonist, Hamidou, I had cast Paul Smith, an Israeli/American actor who I had met and read with in New York. He had a mysterious past with a checkered résumé including Brandeis and Harvard; the Israeli Six Day War; kung fu movies in Taiwan and even a stint fighting with Castro against Fulgencio Batista in Cuba. Most recently he had done a number of spaghetti westerns in Italy—in one of them he had famously carried home his dead horse on his ample shoulders. Our role would be less strenuous, but we did want to take off his beard and shave his head, which made him very nervous, as his wife had never seen him without a beard. Also, he proposed that we should insure his hair in the event that it never grew back again. As he was quite bald anyway, it would have been hard to get a Las Vegas bookie to take odds on that occurring, let alone the Lloyds insurance companies.

Filming began in Malta on September 12th, 1977. We had a very strenuous shooting schedule— 53 days. It would mean six-day working weeks and often seven, which, not unsurprisingly, proved very unpopular with the crew, particularly when we went twenty-one days at one point without a break. The crew, although overworked, were mostly young and could cope with the exigencies of the tough schedule. Almost all of the crew, in every department, had worked with me on commercials in London and so there was an instant understanding and cohesion to the filming.

Apart from Alan Marshall and David Puttnam to support me, I also had my usual cinematographer, Michael Seresin; production designer, Geoffrey Kirkland and editor Gerry Hambling—all of whom went on to make many films with me over the subsequent years. The costume designer was the extraordinary Milena Canonero who was usually accustomed to more elegant costumes, but soon got into the spirit of the sweat and grime of our ‘prison’.

Odd things happen when a film crew works so intensely and so relentlessly on such a dark and brutal subject and probably we all went a little crazy along with the actors during filming. The set was confining enough, but so too was the rock of an island on which we found ourselves with just a handful of restaurants (with a culinary legacy that owed more to Britain’s Royal Navy than to fine Mediterranean cuisine) and a crew, surrounded by barbed wire in a Victorian, fort working a 14 hour day whereupon they were bussed back to the bar of the 60’s Hilton.

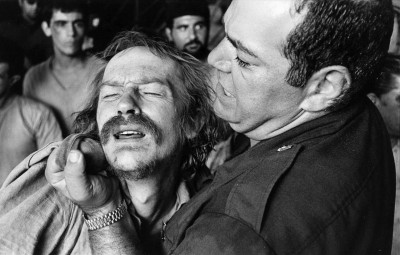

The opening scenes with Paul Smith and Brad were quite traumatic because it became clear that Paul Smith was intent on being as physical as possible. The British stunt coordinator Roy Scammell had instructed Paul so as to ‘not actually inflict physical harm on Brad’ but to no avail and I, not for the last time on this film, had to make the decision as to what was an illusion created for a movie and what was real harm to the actors. Smith’s overzealous ‘physical acting’ exploded a few times as Randy Quaid and John Hurt bridled against his aggressive excesses, which they thought had little to do with acting. John Hurt finally lost his rag when Smith who, having just broken Paolo Bonacelli’s false teeth with a hefty swipe of his hand, had proceeded to yank the wispy, but real, hairs out of Hurt’s chin.

The opening scenes with Paul Smith and Brad were quite traumatic because it became clear that Paul Smith was intent on being as physical as possible. The British stunt coordinator Roy Scammell had instructed Paul so as to ‘not actually inflict physical harm on Brad’ but to no avail and I, not for the last time on this film, had to make the decision as to what was an illusion created for a movie and what was real harm to the actors. Smith’s overzealous ‘physical acting’ exploded a few times as Randy Quaid and John Hurt bridled against his aggressive excesses, which they thought had little to do with acting. John Hurt finally lost his rag when Smith who, having just broken Paolo Bonacelli’s false teeth with a hefty swipe of his hand, had proceeded to yank the wispy, but real, hairs out of Hurt’s chin.

Suffice to say that Brad gave everything he had to the movie—almost to a fault. At the end of filming he was no longer Brad, but ‘Billy’, convinced as he was that he’d just spent four years in a Turkish prison instead of 53 days on a Malta film set, so intense was his commitment to the part. I had to push him as far as he could go as an actor and there were times when maybe I leaned on him too much as we both pushed everything dramatically to its extreme.

Irene Miracle and Brad Davis

This came to the fore one day towards the end of filming when we did the scene where Susan (Irene Miracle) comes to visit him in ‘Section 13’ for the criminally insane. Brad had been very apprehensive about doing this scene and had taken a swig of cognac for Dutch courage before arriving on set. As sometimes happens in filming, our camera broke at the most inconvenient moment. Worse than that, we had lost our main camera the day before and were waiting on replacement circuit boards from London, so we lost time whilst the camera assistants took the Arriflex camera to pieces. During this unusual forced break Brad grew even more anxious, further fortifying himself from the same cognac bottle and by the time the camera was up and running it was clear he was unable to do the scene except at a 45º angle! The avuncular Alan Marshall tried to sober him up by repeatedly walking him around the fort but we decided to abandon the day’s filming. Brad, as always, was full of remorse and apologized to the entire crew who had been endeared to him for his colossal commitment to the role, if not his eccentric take on the acting process.

John Hurt, on the other hand, was in a world of his own and enjoyed the filming through a haze of rolled-up cigarette smoke, although his decision to not bathe for six weeks made him less than popular to have a drink with at the Hilton bar. He wanted to feel filthy and to have Max’s body odor be part of his persona, which curiously did little to dent his unerring popularity. He also continually looked after the fragile, Brad in a kind, paternal way — personally and professionally. John was surprised to find himself for once not to be the most eccentric member of the cast as Brad, before each take, did handstands, press-ups and peed lengthily into a metal bucket.

The weather was unrelentingly hot, the hours long and the work intense, but it was, curiously, a remarkably good-humored film considering the draconian work schedule and the appalling food dished up by the locals and the British caterers. I was mentioning one day at lunch that I had eaten corned beef and tomatoes every day for forty days when Randy Quaid suddenly arrived. There was whispered panic because he had his arm and neck in plaster, apparently having crashed off the diving board at the hotel pool. Marshall and Puttnam began to panic and called for the already ridiculously overloaded schedule board to see how we could possibly get around one of our key actors being incapacitated with crucial scenes still to shoot. The hushed silence subsided when Randy admitted the whole thing was a hoax, cooked up by the actors and the make-up department and designed to give to give the producers Puttnam and Marshall each a heart attack.

Brad Davis and Billy Hayes

Two-thirds of the way through filming we were visited by Peter Guber who brought with him a gaggle of journalists, as part of a press junket. The party included the real Billy Hayes, who I then met for the first time. It was clear that Billy bore little physical resemblance to the dark haired, green-eyed Brad, the real Billy being strikingly blond with the palest of complexions and a bushy moustache. At this point in the schedule, none of us who had toiled in the sweaty prison set for two months were much in the mood for press pleasantries, but I was struck by how Billy, the same opportunist who taped two kilos of hash to his body in 1970, had so speedily and comfortably taken to his new-found celebrity. The junket lasted just two days and they flew off, leaving us to complete our version of Midnight Express.

One of our more traumatic scenes to shoot was where Billy explodes after Max’s ill treatment and attacks Rifki, culminating with him biting out Rifki’s tongue. The fight had been very carefully choreographed and rehearsed by the stunt coordinator, Roy Scammell and myself with Brad who, as usual, went for broke, bringing a manic energy to the fight, which was, at every moment, on the edge of becoming out of control. The ‘tongue’ was in fact a pig’s tongue that Brad spits out. I became so engrossed in doing this scene that I was quite oblivious to the fact that the crew had slowly withdrawn to the rear of the set, nauseated as they were by the sight of it. For myself, of course, the film making process is an illusion and only when I experienced this scene with an audience months later did I realize how powerful and real it seems.

One of our more traumatic scenes to shoot was where Billy explodes after Max’s ill treatment and attacks Rifki, culminating with him biting out Rifki’s tongue. The fight had been very carefully choreographed and rehearsed by the stunt coordinator, Roy Scammell and myself with Brad who, as usual, went for broke, bringing a manic energy to the fight, which was, at every moment, on the edge of becoming out of control. The ‘tongue’ was in fact a pig’s tongue that Brad spits out. I became so engrossed in doing this scene that I was quite oblivious to the fact that the crew had slowly withdrawn to the rear of the set, nauseated as they were by the sight of it. For myself, of course, the film making process is an illusion and only when I experienced this scene with an audience months later did I realize how powerful and real it seems.

Being isolated on an island in the Mediterranean, it was difficult to send regular dailies of our work to be viewed by the studio. However, David Puttnam took a number of reels of cut footage and selected takes, to show to Daniel Melnick in Rome. Although he was mostly overly flattering about what he saw, he was less than pleased with the Brad and Norbert kissing in the showers. In fairness, this particular scene had been problematic for him ever since the first draft. However, after a while he mellowed towards the scene when it was edited and seen in context.

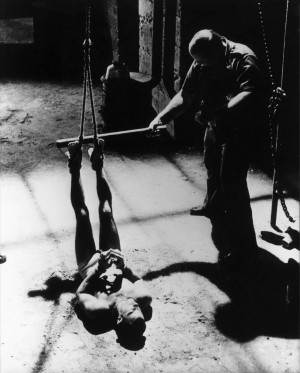

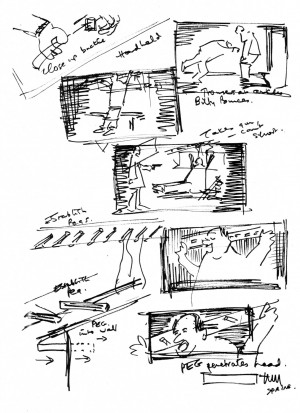

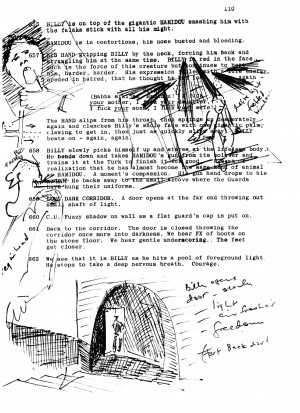

Alan Parker’s script sketches for Hamidou’s death

Our other area of contention concerned the ending. In the first draft of the script, Billy had swum to a fishing boat from an island prison as he did in the book. Our second draft conflated the two prisons and Oliver Stone had written a scene where Hamidou is beaten lifeless with a falaka stick by a manic Billy which, apart from being similar to the Rifki scene, was not entirely convincing considering Hamidou’s physical superiority and Billy’s deteriorating, feeble condition. Also, importantly, from a moral point of view, murder was not something we wanted on Billy’s hands. This had been an unresolved ‘note’ from the studio from our shooting script. It was Roy Scammell who came up with the idea of Hamidou ‘accidentally’ colliding with the clothes peg on the bathroom wall. Geoffrey Kirkland, the production designer, had rigged a peg that depressed into the wall on impact and, with blood capsules behind Hamidou’s head and with apt sound effects and Gerry Hambling’s deft editing it all made for a convincing, nasty, but accidental death.

This led to our next difficulty, which were the actual end scenes of the movie. The shooting schedule had for weeks said, “Thursday 3rd November: ‘UNIT TRAVELS TO GREECE’. The last ten pages of Stone’s script had called for a final act, which had Billy being chased across poppy fields by tanks and border guards, replete with explosions and machine gun fire near Edirne on the Turkey/Greece border, where he eventually swims across the Maritsa river to freedom. It was very formulaic and curiously at odds with the originality of the rest of the script and certainly didn’t sit comfortably with the film I had shot.

This led to our next difficulty, which were the actual end scenes of the movie. The shooting schedule had for weeks said, “Thursday 3rd November: ‘UNIT TRAVELS TO GREECE’. The last ten pages of Stone’s script had called for a final act, which had Billy being chased across poppy fields by tanks and border guards, replete with explosions and machine gun fire near Edirne on the Turkey/Greece border, where he eventually swims across the Maritsa river to freedom. It was very formulaic and curiously at odds with the originality of the rest of the script and certainly didn’t sit comfortably with the film I had shot.

After Billy dresses in the guards uniform, I had added a scene where the last gate guard actually throws Billy the keys to his freedom. I had made much of this in filming and when the door finally opens at the bottom of the stone stairs and a crack of light bleeds in, Billy and the audience feel the fresh air of freedom for the first time. The moment I shot it, I felt that we had reached the natural end to the film. We also did a scene outside in the street where the army jeep comes perilously close to perhaps capture, but continues onwards (my homage to the last scene of The Third Man, only in reverse) and finally Billy runs off to liberty. I had frozen the frame on his triumphant leg kick much as I had done at the front of Bugsy Malone and this absolutely brought the film to its conclusion. For the same reason, the addendum of Billy’s homecoming at Kennedy Airport in October of 1975, written as live action, I decided to shoot as black and white still images so that this section didn’t interfere with the main movie. Also, the decision was as much pragmatic as creative, in that we could never replicate Kennedy Airport in Malta! The stills were shot at Valletta Airport by our unit photographer, David Appleby. Puttnam had the task of explaining our new ending to the studio. Needless to say in Los Angeles, Melnick and, particularly, Guber (whose idea the action/chase ending was) were not pleased with us dumping the scripted ending and reminded us that we were legally bound to shoot the agreed script. As Alan Marshall said at the time, “They wanted an escape movie and we’re giving them a prison movie.” Puttnam, forever swift of foot, came up with a compromise which would allow us to complete a cut of the film our way and, once Guber and the studio had seen it, they could decide if we were right or wrong. If wrong, then we would re-form the unit and go to Greece to shoot their scripted ending. If we were right, we would have a great ending to the movie and save them considerable bucks in the process. The possibility of ‘saving considerable bucks”, swayed it, as always, for the studio. The sudden curtailing of our planned schedule meant an early return to England for the crew on a chartered plane. It was remarked that we were already spending the saved budget, however it was the cheapest way home for the large crew.

Afterwards

Back in England, we shot a couple of pick-up shots at Shepperton Studios (where we were based for post production) rebuilding a small corner of the Malta prison set mainly to clarify a couple of transitional moments where Billy leaves the strict security of ‘Section 13’.

We were not allowed to film in Istanbul, and so we were quite perplexed as to how to get the required exterior scenes we needed to intercut with our Malta footage. My friend Hugh Hudson, who shared offices with Alan Marshall and I in Soho, when we made commercials, had offered to go to Istanbul to shoot second unit. Under the guise of the Benson & Hedges commercial script I had written, he went to shoot the scenes we needed to incorporate into our cut — namely the opening Istanbul establishing wide shots and the Gelata Bridge, which symbolically joins Asia to occidental Europe.

Hugh had also suggested to me a composer he had worked with in commercials called Vangelis Papathanassiou. I proceeded to experiment with Vangelis’s music, laying it all the way through the first cut of the film, and we were very pleased with it. As our umbrella production company, Casablanca, was also a record company, I was politely asked to try an alternative — the soundtrack album not being something they were keen to give up. Neil Bogart, the head of Casablanca, suggested Giorgio Moroder to me. Giorgio was very successful at the time from work writing and producing the Donna Summer hits, which were Casablanca’s big success story, although Giorgio had never done a film score at that point in his career. I said that I was quite happy with Vangelis, but Guber suggested that I try working with Giorgio and if it didn’t work out then we would go back to Vangelis. I went to Munich, where Giorgio had his studio, and we began work on the score. It went very well: being all electronic, we could build up the layers of sound with great control as Giorgio experimented with repetitive rhythms while watching a small monitor showing the cut footage, at the Musicland studios— a long way from a full orchestra striking up on a film music sound stage. It was a very rewarding time and Giorgio’s score went on to win the Academy Award. (As a footnote it’s worth noting that Hugh Hudson used Vangelis for the score of his first film, Chariots of Fire, in 1981, and Vangelis also won the Oscar.)

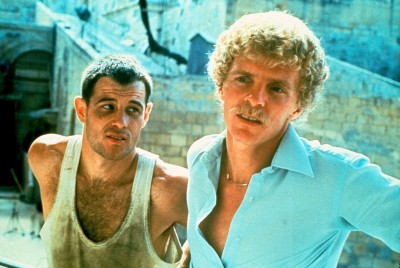

Norbert Weisser and Brad Davis

In March of 1978 we took the finished cut, or our finished cut, at any rate, to show to the assembled executives at Columbia. Anyone else would have shipped the film, but Alan Marshall would not allow the first cut out of his sight and so the two of us took it with us to Los Angeles for our arranged screening. As fate would have it, Heathrow was closed for twenty four hours because of a strike, and so Alan Marshall and I hand-carried the film to France, hiring a taxi to take us to Dover and then hobbled on board the car ferry carrying the film cans. At Calais we paid an exorbitant amount of import tax on the film and then caught another taxi to Paris where we boarded the plane to New York and then (hopefully) onward to Los Angeles. As this was an unscheduled journey, we, and the film, were held up by customs in New York. They had recently confiscated Oshima’s so-called ‘pornographic’ film Realm of the Senses and so the customs men were nervous about the large pile of cans we were suspiciously hand carrying. Alan Marshall and I stood there with the film cans of the first cut of the film as the New York customs man quizzed me, “Is there any violence in this film, sir?” “Yes,” I answered. “Is there any sex in this film, sir?” “Yes,” I answered.” “Is there any homosexuality in this film, sir?” “Yes,” I answered, clearing my throat. He called for his supervisor.

Eventually, we arrived in Los Angeles and Daniel Melnick, David Begelman, the head of the studio, plus assembled executives sat down to watch our cut. As the film went by they were very generous about what they saw, but it was obvious they were nervous as to the ending. As the conclusion of the film approached, calamity struck as the projectionist inexplicably missed out the penultimate reel. This consequently meant that Billy, Max and Jimmy were discussing escape in their bunks and the very next cut Billy is miraculously walking out of the prison. The executives in the room looked at one another as if we were out of our minds to suggest such a paranormal conclusion. Puttnam and Marshall leaped out of their seats and ran to the projection box. The projectionist had been confused by the British system of labeling reels alphabetically, as he was used to numerically marked reels. His ‘k’ reel had come before ‘j’ in his alphabet. Puttnam threatened to inflict grievous bodily harm on the hapless, dyslexic projectionist but was restrained by an unusually calm Alan Marshall who began rewinding the film. The reels were re-ordered and our ending was graciously applauded and approved by Begelman and Melnick.

Peter Guber’s great contribution, apart from spotting and optioning the original materials, was leaving us all alone to make the movie and then to cleverly and aggressively market the finished film. The film didn’t cost very much and its potential was ultimately deemed significant, hence we had the full resources and finances of a major studio behind a very small film. It was one of the first films to cost more to market and distribute than it did to make. Columbia’s head of distribution, Norman Levy was not enamored with the film at first, thinking it a tough sell. But Guber won him round and the power of Columbia’s distribution system and Guber’s assertive promotion is what turned a small film into the major success. It was Guber who was keen not to subtitle any foreign language in the film but he wanted a “Based on a true story” caption. His reasoning for no subtitles was the fear of it appearing to be an “arty” European film (a kiss of death with an American audience). The important factor in the use of a “foreign language” was to alienate our main character and the audience where they were unsure what had been said, and so we dropped any translated subtitles for the English language version.

Having not been able to cast in Turkey, I had assembled a potpourri of character actors (Armenian, Greek, Cypriot, Maltese and Italian) with a mélange of sounds that had some connection to Turkish (depending on how fluent you are in Turkish). I left this mélange as it was (and not dubbed) because, to be honest, the Turkish aspect of things was never at the forefront of our minds. Being a long way from Turkey in a British army fort in Malta and having created our own “Sagmalcilar” prison with a story and characters that had evolved as we went along, we had arrived in some foreign, alien place that could be Turkey. It also could have taken place in any number of countries with attitudes to drugs not equitable to those in the west and with equally harsh prison conditions.

The “anti-Turkey” criticisms aimed at the film, took us a bit by surprise, it has to be said. Not to appear too disingenuous, this was not a factor when Oliver wrote his screenplay or when I made the film. We were young filmmakers, hell-bent on telling a good story about what we saw as injustice of disparate legal and prison systems and perhaps, in our zeal to tell our story and make our points, some light and shade were lost. The “good-guy” Turks got left out. This is easy to say in hindsight with the intellectual and political maturity that comes with the passing years. But the raw energy and voice of the film, it’s uncompromising visceral power, still remains as fresh and modern as a piece of filmmaking today, belying its thirty years —this too came from the same youthful enthusiasm, single-mindedness and naivety.

The caption, “Based on a true story,” was also misleading. Certainly it was based on a true story. But that didn’t mean that it was a true story. As I have tried to recount here, it had gone through too many hands and minds with too many agendas for it to be totally true. What is truth anyway, with such a project? Billy Hayes was caught smuggling drugs and was convicted. Unreliable memory (which we all have) probably moves truth away, somewhat, from reality, as did his own hubris. He escaped with some notoriety and sat down with a ghostwriter, William Hoffer, who added his literary slant to the story to satisfy the publishing needs. Oliver Stone wrote his screenplay and undoubtedly moved further away from the original ‘truth’, adding his own unique slant to the proceedings. Then there were the exigencies of the studio and the producers own agenda, as to the needs of commercial success (and also awareness of what plays to the whims of a [mostly American] audience.) To this end, Stone’s screenplay was altered accordingly.

I then did my version of the story when I made the film and I moved it even further away, creating the world of a mythical Billy Hayes, as I had imagined it. The beauty of film is that it is a totally organic process. It’s not a script, a production call-sheet or a set of studio notes. It’s a living thing, which, through the magical metamorphism of the film process — principally the sweat and labor of the film crew — becomes a film. Every day fifty people, actors and crew, interact and create their version of the day’s work — about which there can be a million different interpretations: sometimes creating a good film, and sometimes a dud.

Undoubtedly, the dexterity and imagination of Gerry Hambling in the editing process moved the story again away from whatever now passed as ‘truth’. But what is truth when you’re making a movie for a major American film studio? Come to that, what is truth in any artistic interpretation? Particularly with a story on film where the filmmakers so clearly have their own agendas?

At one of the early screenings of the film with a test audience, I watched a woman dash out of the auditorium and, mistaking a locked office door for a lavatory, promptly threw up in the lobby. I remember saying, ‘Come on, the film’s not that bad’. But suddenly you realize that what flickers up there on the screen for you, as a filmmaker, is an illusion, a thousand shots with fifty thousand Scotch-tape joins. But the effect on an audience is something else. It’s a sobering responsibility. However, when someone tried to burn down a cinema in Holland showing the film I thought that it had gone a little too far. It’s only a movie after all.

The screenings of the film at the Cannes Film Festival in May of 1978 took us all by surprise. It was simultaneously hailed as a masterpiece and also as “the CIA backed, US fascist scandal of the festival”. There used to be a rule at Cannes “that no film screened officially can offend another country’s political sensitivities” (A rule long since ignored.) and so we caused quite a stir. No one was more in shock at the hostile reception than Marshall, Puttnam and myself.

Alan Parker, Billy Hayes, Brad Davis, Cannes Film Festival, May 1978

The Cannes red carpet gala evening was a big success, with Billy Hayes dressed from head to toe in eye-catching white, standing out from the traditionally black tuxedoed crowd. But the next day at our press conference I was savaged, particularly by the French press. Walking along the beach, Puttnam and I went over our options, adamant as we were to be taken seriously. Just then, we noticed the usual gaggle of twenty or so Cannes photographers shouting to a girl in the sea. “Take it off. Take it off,” they yelled. The girl dutifully obliged, taking off her bikini to reveal her breasts. It happens all the time at Cannes — some unknown girl takes the opportunity to show a little flesh and enjoy her 15 minutes of fame. Except the girl was Billy Hayes’s girlfriend and we were asked if this was publicity for the film. Puttnam stormed to Hayes’s room and Billy and the girlfriend were in a car to Nice airport within the hour. Once the film was released, its visibility forced Turkey to put out a warrant for Billy Hayes’ arrest on Interpol, which somewhat curtailed his subsequent foreign travel.

The French did ultimately warm to the film, however. It ran at the same cinema in Paris continuously for nine years. Now and again, they renewed the very scratched print.

The film went on to win six Golden Globes, the most for one film since On the Waterfront. Oliver collected his award and proceeded to make an interminable, rambling speech about prisoners unjustly incarcerated around the world. The whistles and boos at what is known as a ‘Vanessa Redgrave moment’ in US award circles, forced the MC, Chevy Chase, to take his arm and escort him off stage. Fortunately, it didn’t affect his chances of an Oscar®, which he also went on to win, for best screenplay. Giorgio’s win for best score was the first all-electronic score to win an Oscar®.

David Puttnam, Peter Guber and Oliver Stone all went on to win more Oscars. Danny Melnick even went on to produce a film with a gay theme in 1982, Making Love.

Billy Hayes is involved in the entertainment world.

Among other movies, Brad Davis went on to make Querelle with Rainer Werner Fassbinder. A baffling, brilliant and tormented soul, Brad was much loved by all of us on the film crew despite his sometimes perplexing, unpredictable eccentricities. He gave every last ounce of his being to his role in Midnight Express, No actor could have given more. He sadly died of AIDS in 1991.

Among other movies, Brad Davis went on to make Querelle with Rainer Werner Fassbinder. A baffling, brilliant and tormented soul, Brad was much loved by all of us on the film crew despite his sometimes perplexing, unpredictable eccentricities. He gave every last ounce of his being to his role in Midnight Express, No actor could have given more. He sadly died of AIDS in 1991.

Text © Alan Parker. All Midnight Express photos © Columbia Pictures, Inc. Stills photography: David Appleby. Cinematographer: Michael Seresin