THE MAKING OF THE FILM

BY ALAN PARKER

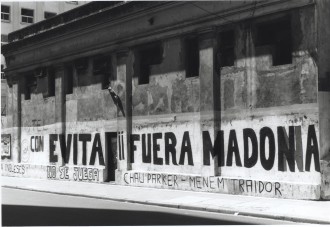

When I arrived in Argentina to begin filming Evita, on the drive from Buenos Aires airport, every wall was covered with giant graffiti proclaiming “Fuera Madonna.” They were huge colourful signs with painted letters ten feet high, stretching forty feet across each bridge we drove under. “How nice of them to welcome us.” I said, from the back of the minivan. Our local production manager nervously explained that the graffiti was less than welcoming, roughly translating as “Piss off Madonna.” A wall outside our hotel, like many others, also had the encouraging line “Death to Alan Parker and your English Task Force”. (During the Falklands War the British military was called “The task force”.) The angry spray painted graffiti were all signed by a group called , ‘The Commandos of the Peronista’. I made an observation that the lettering on the dozens of signs was very similar and that they always spelled ‘Taks Force. With optimistic expectation I ventured the thought that maybe all this hatred directed at us could be the work of just a single dyslexic commando. In Argentina, to the Peronist faithful, Maria Eva Ibaguren Peron was a Saint. To the ‘Radical’ opposition she was an avaricious, despotic, conniving whore – perfect material for a film.

The graffiti welcome outside our hotel in Buenos Aires

Someone once said, “He who leaps into the void owes no explanation to those who stand and watch.” One of the difficulties a film maker has in any explication of the nuts and bolts and Sturm und Drang of making a film is that the chronological order of the story bears no resemblance to the lunatic logic of how things were actually achieved. But I will attempt to start from the beginning.

The common claim from most people who write about Argentina is that an objective historical perspective runs counter to Argentinean culture, particularly when it comes to the passions they have for and against Eva and Juan Perón. It seems that the personal memories that historians rely on are partisan at least and fragile at most. Also, the miserable political legacy of years of interrupted democracy and numerous military dictatorships have played havoc with the reliability, or even existence, of historical documentation.

In his excellent essay, The Return Of Eva Perón, V.S. Naipaul quotes a poem by Jorge Luis Borges (an Anti-Peronist) which describes more eloquently Argentina’s national selective memory:

A cigar store perfumed the desert like a rose.

The afternoon had established its yesterdays,

And men took on together an illusory past.

Only one thing was missing—

the street had no other side

So how does one go about making a balanced and accurate film on Eva Perón when myth and reality collide at every turn of her story? Many saw her as a lady bountiful, champion of the disenfranchised, nothing less than a saint. Others saw her as an opportunistic, meretricious, conniving devil incarnate. Eva called herself, “a sparrow in a great flock of sparrows.” Her supporters called her “The Lady Of Hope” and her detractors, “the charming child with a loaded gun.”

This dichotomy was reflected in the reaction to the original musical. On one side of the divide, Tim Rice had acknowledged the importance of Mary Main’s (Maria Flores) book, Evita: The Woman With The Whip, as being important in his research. Maria Flores was an Anglo-Argentine historical novelist who, it has been contended since, drew her information mostly from the opposition and oligarchy, and hence her book (published in 1955 and subsequently often quoted by detractors) was little more than Anti-Peronist gossip. On the other side of the divide, the anti-Evita camp equally saw the musical as Eva’s unwarranted glorification. (Including, it has to be said, the subsequent military dictatorships which banned all performances of Evita and the importation of the record.)

How can you accurately describe a woman whose image has been used as a flag by both left-wing guerrillas and right-wing extremists?

If the reason for this film is Eva Perón, its genesis as a creative work, of course, resides with Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber. Tim was the first to be taken by the idea of a modern, sung-through opera on the life of Evita. A one-line synopsis of her rags-to-riches story and tragic early death is not just the stuff of musical theater or the Hollywood dream machine, but also has resonance in the classic operas from Tristan und Isolde to La Bohème. Tim and Andrew had originally conceived and executed it as a complete, cohesive and conceptual recording before it was performed on stage (as they had done with their previous collaboration, Jesus Christ Superstar). The album was released in Britain in November of 1976, and the single release of “Don’t Cry For Me Argentina,” sung by Julie Covington, had gone to number one in the British charts a month earlier.

My initial personal involvement with the project began soon after the album came out. I had inquired of their manager, David Land, if they had thought of making a film of the record, being as it was for all to hear (and see) completely cinematic. I was told that “the boys” wanted to put it on stage first, and so I bowed out gracefully. Hal Prince had been persuaded by Andrew to direct the show and it opened to great success in London in June, 1978 with Elaine Paige as Evita. The show subsequently transferred to Broadway in 1979 starring Patti LuPone, where, despite mixed reviews, it ironically won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Musical and seven Tonys, running for 1,567 performances.

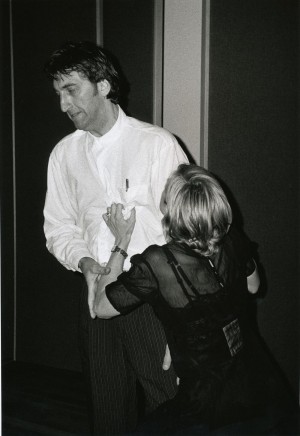

Robert Stigwood and Alan Parker, Budapest, 1995

I had the pleasure of being invited to the Broadway opening by the producer, Robert Stigwood. Robert asked me if I would like to make a film of Evita and I told him I’d give him my answer when I had finished my film, Fame, which I was then shooting in New York. After completing Fame and while enjoying some rest on the Caribbean island of St. Maarten I received a call from Robert, who said he was steaming toward the island in his yacht.

I’d always been a tad wary of Robert’s enthusiasm — ever since 1977 when he went to great lengths to encourage me to do the film version of Sergeant Pepper and hired a hundred out of work actors to picket and heckle the hotel where I was staying in Los Angeles. The crowd, carrying balloons and placards, chanted, “Alan Parker, Sergeant Pepper is after you.” There are few moments of embarrassment in my life to match this episode.

In the Caribbean, after a day of sumptuous hospitality on his boat, the like of which no mortal but Robert can provide, he asked me if I wanted to play tennis. Forever the dutiful guest, I obliged, and the two of us were whisked across the bay in one of his launches to a nearby hotel tennis court, where we disembarked and watched the launch speed back to the yacht. The problem was that the tennis court was locked. Robert and I, now completely stranded, walked down the dusty main street. Finally, out of the blue, he said, “So, are you going to make Evita or not?” I mumbled that after Fame I didn’t want to do back-to-back musicals, and so my answer was “No”. Robert said nothing for a while, and then suddenly started bashing me with his tennis racket. I ran back to my hotel. This is a true story.

For fifteen years I watched as the film of Evita was about to be made, and the various press releases were printed in the media. I have been furnished with the various news clippings from those years, and would first like to mention the stars that would supposedly be starring in the film. They include: Elaine Paige, Patti LuPone, Charo, Raquel Welch, Ann-Margret, Bette Midler, Meryl Streep, Barbra Streisand, Liza Minnelli, Diane Keaton, Olivia Newton-John, Elton John, John Travolta, Pia Zadora, Meat Loaf, Elliott Gould, Sylvester Stallone, Barry Gibb, Cyndi Lauper, Gloria Estefan, Mariah Carey, Jeremy Irons, Raul Julia and Michelle Pfeiffer. And then there were the directors: Ken Russell, Herb Ross, Alan Pakula, Hector Babenco, Francis Coppola, Franco Zeffirelli, Michael Cimino, Richard Attenborough, Glenn Gordon Caron and Oliver Stone.

So why didn’t it get made until now? And with none of the individuals mentioned above? I’m sure I don’t know. All I do know is that all those years, I sort of regretted saying no to Robert in that dusty street. So I was glad that everything came full circle when I was asked to make the film again by Robert Stigwood and Andy Vajna at the end of 1994.

When I began work on the film, the incumbent actress to play Evita was Michelle Pfeiffer. She had waited such a long time to do the film that she had even had a baby in the meantime. I met with Michelle, whom I greatly admire, and it was clear that with two small children she wasn’t about to embark on the long Lewis and Clark journey I had in mind—a long way from the comfort of nearby Hollywood sound stages. While spending Christmas in England in 1994, I received out of the blue a letter from Madonna. (I had developed a remake of The Blue Angel with her some years previously, but it had bitten the Hollywood dust.) Her handwritten, four-page letter was extraordinarily passionate and sincere. As far as she was concerned, no one could play Evita as well as she could, and she said that she would sing, dance and act her heart out, and put everything else on hold to devote all her time to it should I decide to go with her. And that’s exactly what she did do. (Well, she didn’t put everything on hold, as she did get pregnant before we finished filming).

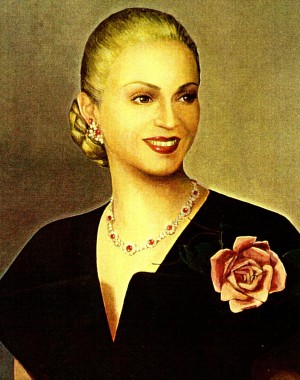

Portrait of Madonna as Eva Peron

Antonio Banderas was already the favorite to play Ché. I viewed a tape of him singing in a cold audition he had done years before, and I was easily convinced. I flew to Miami where he was filming and had dinner with him as he sang aloud, to the surprised pleasure of the surrounding tables, every song from the show which he already knew by heart. Even the songs his character, Ché, doesn’t sing in the movie.

For Perón, I decided on Jonathan Pryce. Apart from being a brilliant, classically-trained British actor, he had also created the lead role of “The Engineer” in the stage musical, Miss Saigon, for which he won a Tony Award. I had also most recently seen his bravura performance as Lytton Strachey in Carrington. Jonathan, although taken by the script, first wanted to meet with me before he committed. As he was on holiday in France at the time, I flew to see him at Marseilles airport, where it had been arranged by his London agent that we could conveniently have our meeting. Unfortunately, Jonathan’s New York agent thought it unwise, and told him not to go, neglecting to tell me that the meeting was canceled. I consequently spent four hours in the Marseilles airport arrivals hall, lugging around a very heavy carrier bag of research material on Juan Perón, drinking many cups of coffee and glasses of Pastis while chasing after every tall, English-looking man that I could find before getting the evening plane back to London. (I’m pleased to say that Jonathan no longer has that New York agent.) Finally, we did meet back in London and he was on board.

My initial priority had been to write my screenplay. Armed with every filmed documentary made on Eva Perón, every possible book in the English language on the Peróns and Argentina, and any old news cuttings I could get my hands on, I did my research. When Tim did his original libretto there was very little for him to work from, but ironically the success of the musical had spawned many biographies. My intention was to write a balanced story, as thoroughly researched as possible, inspired always by the heart of the original piece, which was Andrew’s score and Tim’s lyrics. I ignored the stage play completely, as the theatrical decisions that Hal Prince made bore little relevance to a cinematic interpretation. And so I went back to the original concept album from which I had wanted to make a film eighteen years previously.

In the stage version, Hal Prince had insisted that Ché, the Brechtian, everyman narrator, be clearly identified as Ché Guevara (complete with beard, beret and fatigues) for its obvious, immediate stage effect. My own script refers to him merely as “Ché” (a common nickname in Argentina, like “buddy” is in the U.S.) Suffice to say that Ernesto “Ché” Guevara, born in Rosario, Argentina in 1928, almost certainly never met Eva Perón. He entered Buenos Aires University in 1948 to study medicine, and qualified as a doctor a year after Eva’s death. When the musical was written, Guevara, a revolutionary, iconoclastic presence which had adorned many a bedroom wall in the 60’s (including my own) was still relevant, and the coincidence of his Argentinean birth became an excellent theatrical device around which Tim Rice could construct his libretto. My own feeling was that Ché Guevara’s actual story should not be cosmetically or dishonestly grafted onto ours. Indeed, it probably deserved a film or two of its own. And it wasn’t to be this one. Hence the narrator in my film is purely and simply “Ché.”

By May of ’95, I had finished writing my script—which called for 146 changes to the original score and lyrics—and so, like a mailman offering his leg to a couple of hungry Rotweillers, I sent my first draft to Andrew and Tim. Fortunately, they liked it very much. The next step was for the three of us to get together. It’s no secret that Andrew and Tim no longer have a comfortable working relationship, having chosen not to collaborate for many years. Consequently it was obvious that getting the two of them in the same room together to go through the new work needed was going to be no easy task. After a great deal of tango-ing and juggling of schedules that the two of them are famous for, Tim and I flew to Andrew’s house in the South of France and with me as piggy in the middle, worked solidly and surprisingly productively addressing my 146 music notes. One of the many changes I had made was to rearrange the order of most of the last act, eliminating the prolonged recitative of the original. This called for new scoring from Andrew, and, most importantly, a new song to be written by the two of them. For obvious reasons, Andrew doesn’t give his melodies away too hastily, and the possibility of these two gentlemen ever collaborating again was, I was told by many who knew them well, an idealistic but not overly practical notion.

In New York, Madonna had begun work with the esteemed vocal coach, Joan Lader. She was determined to sing the demanding score as Andrew had written it, and not to cheat in any way. Within three months she expanded her vocal range, finding parts of her voice that she had never used before in her own songs. She had also learned the Evita score from musical supervisor David Caddick, who has worked with Andrew for many years as musical director on his shows.

In September, Madonna, Antonio Banderas, Jonathan Pryce and Jimmy Nail (who plays tango singer Agustín Magaldi) began rehearsals with me in London. My approach to this unusual film genre—being as it is a completely sung-through piece with no conventional dialogue—I was convinced should be as naturalistic as possible, its only theatricality being the fact that it’s sung and not spoken. Any other choices made I felt should be the same as if I were doing a normal dramatic film. (To this end, Madonna dragged Jimmy around the studio, bashing him with her suitcase, as we enacted the scenes as they were written in the script. Mindful of the fact that Jimmy, in his youth, was once in prison for causing grievous bodily harm, I feared for the consequences. However, he was a paragon of English good manners, quietly suffering the bruises inflicted on him. Rumor has it that Jimmy, an avid Newcastle United football fanatic, perhaps only did the film because he thought Maradonna was in it.)

By October 2nd, we were ready to begin recording in London. Our first day in CTS Studios in Wembley, it has to be said, was a complete nightmare (what came to be known amongst us as “Black Monday”). David Caddick had, probably idealistically, suggested that we begin with “Don’t Cry For Me Argentina” with Madonna laying down a guide vocal simultaneously with an 84-piece orchestra. Andrew attended this recording session and was frankly soon apoplectic about everything from the playing of the instruments, to the conductor, to the engineer, to the way the orchestra was configured in the studio to the closeness of the violins to the studio wall. Madonna, equally, hated the experience too, and was close to tears as she wondered, with due cause, what the hell she had gotten herself into. The cozy, creative recording environment she was used to was light-years away from this frenetic musical madhouse as the worlds of musical theater, film and recording were suddenly colliding. It was obvious that I had to put things right.

At the end of the day, ironically, we all gathered in an adjacent studio for a photo call to announce the commencement of recording. Our cheesy smiles belied what we were really feeling as we all put on brave and professional faces as the hundreds of cameras rattled away. That evening, I followed Andrew’s car home and we had dinner in an Italian restaurant near his house. The conversation was heated while the food got cold, but we finally reached positive creative conclusions as, I have to say, we have on every occasion since. I suggested that Andrew and I go round immediately to Madonna’s hotel to talk to her, which we duly did. Between the three of us, we decided how to proceed. Andrew had suggested that we ask the celebrated American conductor, John Mauceri, to come to London to conduct our large orchestra sessions. Madonna, Caddick, myself and Madonna’s vocal engineer would continue all the vocals at Whitfield Street Studios, a contemporary music studio, the ambiance of which was more conducive to the job at hand. Madonna would sing in the afternoons, every other day, to save and strengthen her voice, and Nigel Wright, the music producer who had worked extensively with Andrew would, with Caddick and myself, fill the remaining recording time preparing the multitude of other tracks needed. By the end of the week, the maestro Mauceri had performed his magic with a brilliant catchment of the finest orchestral players in London and all thoughts of “Black Monday” were forgotten. We were on our way.

Everything we recorded was done with the naturalistic philosophy mentioned previously. As we were going to film nearly all the scenes to pre-recorded playback, decisions had to be made in the recording studio that I was going to have to live with during filming. Ever mindful of this, I sat every day with my script in my lap fielding all the questions the actors would ask. In a way, Evita was like making two films, one first in a recording studio and one later with the camera on a film set. Over a period of four months, seven days a week, we did over four hundred recording hours, preparing the 49 musical sections that were required for playback on set. However, we still didn’t have our new song. Finally, while I was visiting Andrew at his country estate in Berkshire to play him the tracks we had recorded, he suddenly sat down at the piano and played the most beautiful melody, which he suggested could be our new song. Needless to say, I grabbed it. However, we still needed lyrics and Tim dutifully began to put words to the music. The vast majority of the original Evita score had been done this way: music first, lyrics afterwards. After many weeks of nail biting, Tim was finally cajoled into writing the lyrics that now accompany the music to “You Must Love Me.” Tim also completely rewrote the lyrics of “The Lady’s Got Potential,” which Antonio sings. (This song, from the original album, had been dropped by Hal Prince for the stage version, and I had resurrected it for my screenplay in order to tell the history of Argentine politics which preceded the Perón presidency.)

Having devoted so much time to the recording, it was vital to return to my “day job” of being a film director, as every department was screaming for my attention. Earlier, in June of ’95, with the help of the State Department and Senator Dodd of Connecticut, I had been granted an audience with Argentina’s President Carlos Menem. I quickly got on a plane to Buenos Aires and the following day was at the President’s private residence, “Los Olivos.” Swarming with dark-suited security people with walkie-talkies and dark glasses, my first impression was that I was visiting Marlon Brando at the Corleone compound in New Jersey. The President was gracious and polite, but as a Peronist he was obviously concerned that the memory of Eva Perón would be respected. Also, because of the previous history of attempts to film Evita in Argentina, I was walking in to a political hothouse due to Oliver Stone’s public utterances when he was seeking permission to film there. Oliver’s manner is not always the material of diplomacy, and this was not the first time I’ve had to apologize for him. The bottom line was that I wanted their cooperation, and most of all the use of the Casa Rosada, the official government house which figures so importantly in our story. I promised Menem respect and accuracy, but reserved my right as an artist to make the film that I saw fit. I told him that I wouldn’t be giving them a script to vet, and that there would undoubtedly be parts of the film that he would disagree with. By attempting a balanced view of Eva Perón, I obviously couldn’t please everyone, especially in such a partisan country as Argentina. As I sat talking to the President, I noticed that to one side of the desk was a very large portrait of Eva Perón, and to the other side a sizable religious statue of The Madonna. Unable to take my eyes off this statue, I began to get nervous that he might ask me who was going to play the eponymous role.

The President concluded the meeting by saying that he was proud of Argentina’s fledgling democracy and therefore he couldn’t say “yes” or “no” to me making the film, but he surely would have a couple of million Peronistas on his back if he granted me use of the Casa Rosada, and anyway, in the nearly hundred years since it was built, no one had ever filmed there. Would Queen Elizabeth allow me to film in Buckingham Palace? I lamely answered that no one would want to. He closed the meeting, enigmatically changing the subject by asking me if I would check out the new Dolby sound system in his screening room. I obeyed. It sounded fine, although I’ve heard that he recently installed digital equipment in anticipation of screening Evita. Outside the gates of “Los Olivos,” I encountered fifty news people anxious to know what had happened in our meeting. As I had been told to keep our encounter a secret, I was a little taken back by the microphones being stuffed through the open car window and indeed that the media had been alerted. It was a first lesson of how things work in Argentina.

It was obvious to me that because of the strong feelings for and against Eva Perón in Argentina, no sensible planning could be done as one would do on a normal movie. As discouraged as I was, I still wanted to make at least part of the film in Argentina, even though it was apparent that it would be impractical, if not dangerous, to shoot everything there. This country is the spiritual heart of the film—a strange, fascinating place that would be difficult, if not impossible, to replicate completely elsewhere. Unlike any other South American country, Argentina prides itself on its “European-ness”, settled as it was by Italians and Spanish with pockets of British, French and Germans. There are half a million Jews and as many Arabs among the population. They say that you can push a plow westward from Buenos Aires across the rich, fertile Pampas for a thousand miles and never hit a stone. There are the tropical Iguazu falls in the north and Antarctic glaciers to the south. From the vineyards of Córdoba to the rocky expanse of Patagonia, the country is truly unique. I’m sure I’m not the first Englishman to be taken by the strange, paradoxical and incomprehensible beauty of it all.

Even if we only filmed there for a few weeks, I was determined to shoot something in Argentina. I had visited Eva’s birthplace of Los Toldos, the town of Junín where she grew up, and Chivilcoy where her father’s funeral took place. At the very least, I would shoot these scenes of Eva’s early life there.

I then visited seven other countries before determining a strategy. I decided to start filming in Buenos Aires, and then move to Budapest, where I thought we could accurately replicate the once beautiful European architecture of Buenos Aires in the thirties and forties, which has since been decimated and replaced by hideous and mindless structures. (Filming any historical recreation of this nature would have been difficult even with complete cooperation.) Whether our stay in Buenos Aires would be shorter or longer than two weeks depended on the irate Peronistas who thought our project heretical and Madonna unsuitable to play their “Santa Evita.”

Our crew was principally English, but we also had American, French, Scottish and Irish technicians too. We freighted many tons of equipment from England and by mid-January our traveling crew of ninety was ensconced in Buenos Aires for our preparations, to hopefully begin filming on February 8th. When I arrived at Buenos Aires’ Ezeiza airport, the hoards of journalists and TV cameras that swamped me with questions was a presage of what was to come. On the drive in to the city, I gulped as I saw the hand-painted graffiti on every bridge and sizable wall that screamed out: “Fuera (go home) Madonna”.

At the time, I remember squeezing my eyes closed and thinking: a). I’ve made a terrible mistake bringing Madonna, Antonio and everyone else into this nightmare. b). If I squeeze my eyes even tighter, it will all be over and I’ll be at the wrap party in London.

David Caddick (music supervisor), Alan Parker (director), Nigel Wright (music producer) CTS Studios, Wembley

Once in Buenos Aires for the duration, my immediate job at hand was to cast the scores of smaller parts and to finalize our dozens of locations. As we were ferried from location to location we were stalked by convoys of paparazzi, who at the time had more cameras than we did. Wherever they got the misguided notion that any movie star would bother to go on a location scout, I’ll never know.

Also, I took the time to absorb my script and think about just how I was going to film this behemoth. The final weeks just before shooting are always a nerve-wracking time for any director, but for the first time, I was more than nervous—I was truly fearful. The enormity of this film and the daunting logistics were a burden enough on top of our obvious security concerns.

Madonna arrived early in Buenos Aires to do her own research and to continue her fittings for the eighty-odd costume changes she has in the film. She was naturally upset by the unwelcoming signs that greeted her, but her greatest immediate problem was the crowd of fans and paparazzi camped outside her hotel keeping her awake at night and restricting her movements. She had made her own contacts and began a slew of meetings with elderly Peronistas and also anti-Peronists as she gathered her own personal research on Eva. Meanwhile, I continued my diplomatic tangos with cabinet members, ambassadors, government officials and army generals with regard to our quest for the balcony of the Casa Rosada and the many other locations for which we needed permission. Although all of them gave me the party line—fearful as they were of the extreme Evita-ists in the Peronist party—I never gave up hope, although, sensibly maybe I should have. Apart from the historical importance of the actual Casa Rosada balcony, “Don’t Cry For Me Argentina” is the heart of the score and the most well known “scene”. I made it clear that we had made contingency plans to build the entire facade at Shepperton Studios in England. My production designer, Brian Morris, had already photographed every square inch of the Casa Rosada and his construction manager had been moved on by military guards a dozen times whilst measuring up with his tape. In other words, I was going to shoot the Casa Rosada whether they gave me permission to use their one or not. The pro-Peronist press attacked us daily, even though they had no knowledge of what we were doing, and the news clippings piled higher and higher from around the world as we read about how unwelcome we were in Argentina. There was nothing to do but take it on the chin and forge onwards.

With our core crew of ninety and over 150 additional Argentinean crew, we were a small, self-contained army and our juggernaut just rolled onwards. Most of my crew had worked on many of my previous films, but it was the first time I had worked with the cinematographer, Darius Khondji. Darius, a Frenchman of Persian descent, I once described as a cross between Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Fernandel. His continual brilliance (and shadows) and affable personality made the filming a constant delight, as he integrated perfectly with my usual camera crew. Except that he was French. As in, “Darius, why have you ordered all these dogs?” as I inquired testily one day at the Buenos Aires dockside. “Dogs?” he replied. “Yes, dogs. The art department have delivered twenty poodles.” He shrugged his shoulders in the way that only the French can. “No, I asked for poodles, like when it rains.” The assistant directors and I countered in unison, “You mean puddles.” He stared at us as if we were mad, “Yes, poodles.”

Through the streets of Buenos Aires and the Pampas beyond, the paparazzi and sleaze journalists from around the world continued to follow us everywhere, sidling up to crew members with a hope of digging up some dirt on Madonna or Antonio, but they gradually grew despondent as it dawned on them that we were just making a movie. And, maybe, a good one.

Down town Buenos Aires. Scene from the film.

There was no way that we could keep them away, as we were filming out in the open. We recreated the Buenos Aires streets that Eva first encountered in 1936, involving period vehicles, thousands of costumed extras and entire street-lengths of art direction. No easy task in the center of a busy city of ten million people. (Although we did film on Sundays, when most Buenos Aires “Porteños”—and the paparazzi—were either in church or, mostly, sleeping off their very late Saturday nights.)

Fed up one day with being constantly buzzed by paparazzi helicopters whilst we were filming, I made a rude gesture into the sky. The next day, Crónica, the extremist daily, ran a picture of me, on the end of a 1000mm lens, flipping my finger with a caption declaring my disrespect for Eva Perón.The press madness culminated for me during a visit I made to the men’s room of the Marriott hotel after returning from a hard night’s work in La Boca (the crazy—and dangerous—dockside area of Buenos Aires). As I stood at the urinal, a journalist rushed in and positioned himself next to me. I modestly hunched over for a little privacy as the gentleman brandished his tape recorder in front of my face with one hand whilst he unzipped his fly with the other. He jabbered something like, “What did you think of the disgraceful sex whore playing the part of Madonna?” I wasn’t quite sure what he meant, as he obviously hadn’t got past his first Berlitz tape. “She’ll do just great,” I offered, knowing that the sound of my voice wouldn’t be heard on the tape over his very loud peeing. As he continued to jabber away, I just shrugged my shoulders to be left alone and finally he rushed out, as if he had obtained some scoop. I could see the headline in Crónica: “Scandal! Parker confirms worst fears: Madonna will be played by Madonna.” As I washed my hands, wondering how much crazier this could all get, I suddenly heard a cellular phone ring in one of the adjacent lavatory stalls. Behind the closed door I heard the occupant answer, as he pulled at the toilet roll, “Yes. No. Parker won’t talk. But listen, I just overheard him doing an interview.” As the weeks went by and our cameras kept rolling, the fans, politicians, journalists, paparazzi and flag-burning, wall-painting “commandos” bothered us less and less as our endeavors came to be embraced by the public at large (especially the many whom we employed).

Whether because of this attrition or some other reason, things suddenly turned for the better. Madonna, through her network of Peronist elderlies had managed an unofficial, personal meeting with Menem. Madonna and I were having one of our regular script meetings when she got the call. As she dashed out the door, I told her to take her CD of “Don’t Cry For Me” with her, and she rushed off to meet the President. In her one hour meeting, Madonna probably achieved more than the rest of us—skiing on the diplomatic treacle—had done in nearly a year. A week later, we were summoned to an official meeting with the President. Jonathan, Antonio, Madonna and myself sat on one side of a large table at “Los Olivos” nibbling the President’s famous pizza.

After much small talk and diplomatic tap dancing, Madonna suddenly said to the President, “Let’s cut to the chase here. Do we have the balcony or don’t we?” The oleagineous Menem smiled and nodded, “You can have the balcony.”

The Casa Rosada, Buenos Aires

Soon after, utilizing every lamp, banner and costume that we had with us, we were filming in front of the Casa Rosada with 4000 extras. When Madonna came out onto the balcony and began singing “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina,” the crowd went crazy. As did all of the crew. On the second night of shooting there, as we filmed the reverseson the crowd, I stood with Madonna on the balcony. With all of the documentary footage imprinted in the back of our brains, it was impossible not to be moved when we were standing in the same spot where Eva stood looking down at thousands of adoring crowd. Suddenly it wasn’t just the illusion and replication of film. It was strangely real. We shot throughout the night and, as the sun came up in the morning, we all quietly hugged one another. I think we all felt that we had, in five weeks, done all that we had set out to do and more. We had overcome the media bombardment, as many wished – and expected – us to fail. I felt that I had captured the heart of our story on film and we were leaving with, an albeit guarded, sense of triumph. It’s not easy making movies and it’s certainly not glamorous. The manic, tormented, hard work, the long upside-down hours, and being constantly ankle-deep in pig shit is the reality. But sometimes it’s really worth it.

It occurred to me, during one particularly sweaty and arduous day’s filming, the irony that we were working a fourteen-hour day, six days a week, sometimes seven without a rest day, making a film about a woman who fought for a five-day week for working people.

And so we moved to Hungary. David Lean said that film crews are the last of the travelling circuses, and that’s what we were as all of us and tons of equipment, costumes and props were transported to Budapest, and we were up and running and shooting in four days. Madonna had gone to New York for a break before joining us, and it was from there that she phoned me. “Are you sitting down, Alan? … I’m pregnant” “How much?” “When is it due?” The calculations of shooting days left buzzed through my head as I tried not to panic. To begin with, we were going to keep it a secret, but the Kafka-esque conversations that I began to have about our schedule with David Wimbury, the line producer, and Dennis Maguire, the first assistant director, defied all logic as they started to wonder if I had finally lost my marbles. It was obvious that Madonna had to make her announcement, and she did.

But there were other obstacles to overcome. I think I have to be honest that the crew, actors, and myself were not taken by Hungary. The inherent misery of the place and the people were a far cry from the pleasure we had experienced in Argentina. The first clue to look for that says everything about Hungary is the blue Danube which bisects the towns of Buda and Pest. It is not blue but decidedly brown. The food, like so much else, is a dreadful legacy of communist austerity and a more traditional cholesterol-packed Kamakaze dive into an early death. When we arrived, shooting mainly outdoors, we thankfully had no snow, but it was terribly cold. And then the unique Budapest cold/hot weather collision hit us. For some geographic reason, there is no spring in Hungary. The Russians didn’t steal it – as they stole everything else from this country – Budpaest never had one. As all students of communism know, nearby Prague has a spring but not Budapest. The sudden peculiar rise in barometric pressure gave the crew headaches and nosebleeds and they suddenly turned cranky. (Istvan Szabo, the great Hungarian director, visited the set and told me to be wary of those “crazy weeks”, when apparently many Hungarians ended up divorced, in jail, in an asylum, or jumping off the Liberty Bridge seeking solace in the brown Danube.

The funeral of Eva Duarte De Peron,, filmed in Budapest

Our biggest work in Hungary was to prepare and film Eva Peron’s state funeral. We had analysed the documentary footage of the actual mammoth event and were anxious to replicate it down to the smallest details. To be reading for filming on the first shooting day, the costume department began fitting and dressing the 4,000 extras at 3:30am. The call sheet read as follows: 4000 crowd to include: 50 mounted police, plus horses; 200 soldiers; 50 army officers; 50 foot police; 60 sailors; 60 nurses; 300 working-class women; 100 upper-class women; 51 descamisados; 20 naval officers; 12 naval police; 300 working-class men; 15 palace guards; 8 pall bearers; 60 navy cadets; 60 army cadets; 300 middle-class women; 300 middle class men; 100 Aristo men; 100 boys; 100 girls; 200 male background; 200 female background; 1400 miscellaneous background; gun carriage; coffin; 4 army motorcycles; 2 police motorcycles; 6 Bren carriers; 2 half track military vehicles; 2 fox tanks; 4 army trucks; CGT float, etc., etc. Miraculously, this giant procession was lined up, ready to film in the street by 10:30 in the morning. We shot for two days and the results are on film to see.

As we rolled on through Budapest, the crew continued to complain about everything from the food, to the rashes they were getting from the chemicals that the hotel used to clean the sheets, to the rashes they were getting in unmentionable areas due to the toilet paper (usually experienced with newsprint on it), to working a seven-day week because of the sudden changes in the schedule due to promised locations suddenly becoming unavailable. In Hungary, like so many countries that have survived under the communist boot, telling the truth, like democracy, has to be learned all over again. We had hoped to film in Budapest’s Catholic basilica, but suddenly were refused to shoot inside, even though they had already allowed us to film the exterior some nights before. It seemed that they had survived the years of Nazi occupation, the ’56 uprising, 45 years of communist, atheist oppression, but couldn’t risk our film crew going in there for a couple of hours. Maybe one of the bishops had got his hands on a copy of Madonna’s book, Sex. We will never know. At least our substantial location fee could have been used to stop the cathedral decaying after a century of neglect, crumbling – like most of Budapest – into the street below. Unlike the rest of the buildings in Budapest, it’s salvation can’t be a transformation into a McDonald’s.

The Hungarian press didn’t help matters either. Too stupid and unworldly to be called capricious, they had shot themselves in the foot with a “supposed” interview with Madonna. Desperate for a homegrown story that was remotely interesting to the rest of the world, they filed their story in “Hunglish” on the wire. Garry Trudeau wickedly “reported” it in Time magazine (excerpt):

Blikk magazine: There is so much interest in you from this geographic region, so I must ask this final questions: How many men have you dated in bed? Are they No. 1? How are they comparing to Argentine men who are famous for being on tops as well?

Madonna: Well, to avoid aggravating global terrorism, I would say it’s a lie (laughs). No, no I am serious now. See here, I have been working like a canine all the way around the clock. I have been too busy to try the goulash that makes your country one for the record books.

Blikk magazine: Thank you for your candid chit chat.

Madonna: No problem friend, who is a girl.

After five weeks shooting, we left Hungary. As is apparent from the above, it wasn’t a moment too soon for any of us.

Back in London in the comfort of Shepperton Studios, with most of the crew sleeping in their own beds (without getting a rash) things were suddenly very civilised. We were in a cozy controllable environment of English studio sound stages, where the greatest problem, apart from adjusting the schedule for Madonna’s pregnancy (and Antonio’s wedding) was getting the crew away from their Guinness in the studio bar and back to an afternoon’s work.

We finished filming at 2am on the morning of May 30th. For those interested in the nuts and bolts of film making, I would like to give a few statistics on the shooting of Evita.

We had filmed for 84 days, shooting in 3 different countries, involving over 600 film crew. We had done 299 scenes and 3000 slated shots on 320,000 feet of film with 2 cameras.

Penny Rose’s costume department, with a staff of 72 in three different countries, had fitted 40,000 extras in period dress. Over 5500 costumes were used from 20 different costume houses in London, Rome, Paris, New York, Lost Angeles, San Francisco, Buenos Aires, and Budapest, including over 1,000 military uniforms. Madonna’s wardrobe alone consisted of 85 changes, 39 hats, 45 pairs of shoes, 56 pairs of earrings and as many different hair designs. Almost all of there were handmade in London. Brian Morris’s art department created 320 different sets involving 24,000 different items of props. And so I could go on. I quote these statistics not only to point out the enormity of the task of making a film this size, but to speak up for the scale and effort of the crew involved and to point out that there is still a film industry that doesn’t squander money on stupidity, indecision, excess, hubris and Cuban cigars. In that, wonderful work fuelled by the imagination, professionalism and passion of film technicians who don’t even blink at a 100-hour working week, far from home, frankly, adds up to the movie we have made.

Alan Parker, September 1996

Afterwards

Soon after finishing the film I described the making of Evita as: “…like riding bareback on a crazed elephant strapped to a jet engine, whilst Madonna combs your hair with a razor blade.” Looking back on it after some years now, I view it with more affection. It’s a brave film— a sung through opera— about a difficult subject.

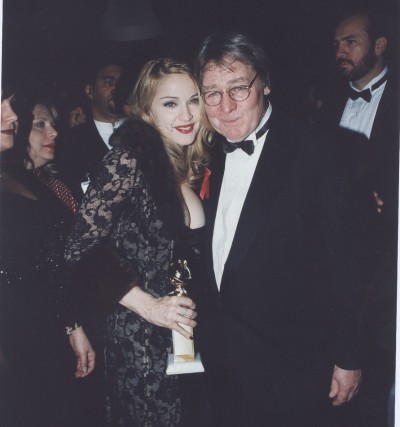

Madonna and her Golden Globes, with director, Alan Parker

Madonna went on to give birth to Lourdes and win a Golden Globe for best actress, however the American Academy snubbed her, not even giving her a nomination, which was a shame because she was excellent in the film. The LA Times ran an article on the curious polarity of opinion in the reviews for the film, under the headline, ‘Fire and Ice’. I suppose the extraordinary hoopla surrounding the film, with the many extravagant “premieres”, rather guaranteed the public removal of our heads on the media chopping block.

We embarked on our own “Rainbow Tour”, just as Eva Peron might have done, starting with a mammoth premiere at the Shrine Auditorium for 4000 people — a quite extraordinary demonstration of Hollywood pomp, it was the usually parsimonious Disney at their most extravagant and efficient — a Magic Kingdom version of a Nuremberg Rally. This was followed by premieres in London, Rome, Paris and Madrid.

In Rome it was pandemonium. The police couldn’t, or wouldn’t, control the huge crowds outside the cinema and Madonna’s security people wouldn’t let her leave her hotel room. Consequently Antonio and the rest of us sat in the hotel bar for an hour and a half waiting for Madonna. This was a lot more pleasant for us then the poor buggers in the cinema who had been sitting in their seats for two hours.

When we finally made it to the cinema Madonna strutted on stage with her usual magisterial, insensate aplomb — completely oblivious to the lack of punctuality. We were saved by a Larry Olivier style speech from Antonio who had grabbed the mic and with great bravado dedicated the evening to the recently deceased Marcello Mastroianni. There was polite applause. It was a cheap shot but it distracted the audience from their previous intention of lynching Madonna and the rest of us.

Buenos Aires press conference for Evita with “El Pirato” Alan Parker

Our final opening was in Buenos Aires, which I had to attend on my own. Madonna and Antonio had declined the Argentinean invitation because of fears for their safety. At the press conference I faced up to what looked like the entire Argentinean press corps. Flanked by two large gentlemen with Uzi’s I felt like a lamb to the slaughter or, as I kidded myself, Daniel in the lion’s den. The newspapers had their own animal metaphors: the headlines said, “Parker in the mouth of the wolf” which I took to be a lucky sign. They harangued me for an hour and a half and thankfully also screamed at one another. “You have shown Evita as a whore shouted someone on one side. “She was a whore!” shouted someone from the other.” “She was our princess” said another. “She was a slut” said another. I’ve had a few boisterous press conferences in my time and this was one of the most theatrical. As the shibboleths flew around the room I was the model of stoic diplomacy. The LA Times reported that I behaved with “dignified serenity” throughout. The only time I lost my rag was after a dozen times of being told the film was not historically accurate, I said, “Would someone tell me what it is exactly that’s inaccurate. Could they be more specific?” They suddenly became sheepishly taciturn until some dopey woman with a TV crew stood up and said that she had spotted someone in the funeral scene who was wearing short sleeves and Eva’s funeral was in winter. Now, apart from the fact that the four thousand extras were wearing coats (it was bloody cold in Budapest) not to mention the thousand uniforms: army, navy, air force, police etc. four thousand of them all correct down to the lapel badges. They didn’t mention that — just one dopey woman in the crowd with short sleeves. I wondered why they stopped there. Of course the film is inaccurate. There’s no evidence that Eva Peron ever sung in verse to Juan all the time, let alone sing, “Don’t cry for me Argentina” from the balcony of the Casa Rosada. To be historically accurate, Eva was tone deaf. Come to think of it, she didn’t live in Budapest either. Or on ‘D’,’E’ and ‘F’ stages at Shepperton studios. And in all the 29 history books I read on the subject, there is never a mention of Eva having a number one record.

For the premiere in Buenos Aires we had to arrive an hour early in order to avoid the threatened protesters who screamed at the ticket holders as they entered the theatre. There was a giant banner that read, (in Spanish) “Alan Parker is a lying rat in the service of the English crown.” The rat was Disney’s Mickey Mouse and the banner was replete with skull and cross bones (as they always referred to me in the press as ‘El Pirato’. I particularly liked that. Possibly pirates are, historically, a more romantic notion to the British than they were to the Spaniards whose gold we kept stealing. The protesters were all bussed in for the evening and arrived late. They were probably having dinner somewhere, over a huge steak, as is the custom, chatting about the various ways they could disembowel me and lost track of the time. The Argentine Vice President, Carlos Ruckauf (Menem was conveniently on a tour of South East Asia) called for a boycott of the film, which caused an even bigger fuss. In one paper, an extremist Peronista Commando even challenged me to a duel with weapons of my choice.

When the film finally opened the protesters trashed a few cinema foyers, smashing the glass display cases and ripping out the posters for the film. In five theatres they set off anti-fumigation smoke bombs and there were a few scuffles but nothing more. Even with all the commotion (or because of it) we still broke the Argentinean record for opening day for a film. What followed was a marketing campaign from Hell” “See it and Die,” “Five Oscar nominations and five fire bombs.” Time Magazine had proclaimed, “You must see Evita,” but in Argentina “See it and burn in Hell” said Cronica, Clarin, La Nacion, La Razon, Gente, Caras and La Prensa. With equal rabidity Argentina’s religious leader, Cardinal Gomez declared, “See it and be excommunicated,” a rather unhelpful comment from a film distribution standpoint.

As a reward for facing the rancour of the Buenos Aires press, Disney sent me back to London by way of the spectacular Iguazu Falls. One of the natural wonders of the world, they’re massive, bordering three countries: Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay. Because of all the press brouhaha everyone recognized me walking around the roped walkways that criss-cross Iguazu. I was continually stopped to have my photo taken with scores of children whose lovely, plump mothers put their sweaty arms around me as we posed for their instamatics. Everywhere I went it was, “Mama, Mama, Alan Parker El Pirato!”

First published Dec, 1996 By HarperCollins

All text © Alan Parker. All photos © Cinergi Entertainment, Inc. Stills photography: Cinematographer: Darius Khondji.