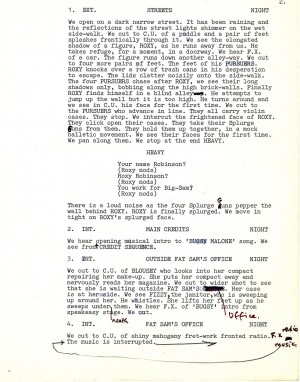

Bugsy Malone

The making of the film by Alan Parker

Because of the needs of DVD, one of the dubious pleasures a director has to go through is the “accompanying commentary” whereby you sit in a dark room and point out all the wonderful things about your movie that the critics seemed to have missed.

Jodie Foster and pie, Pinewood Studios

Watching Bugsy Malone so many years after having made the film, was a bizarre experience for me. My overall impression was that it must have been made by someone who was a good few custard pies short of a tray. It was a lunatic idea that one would only attempt at the beginning of a career, infused as it is with such ingenuousness, yet also with almost manic, devotion. Looking back after all this time, it’s easy to see that we must have been crazy even to have attempted it, but curiously, back in 1975, it never occurred to us for a moment that such an absurd creative notion would not work. As for the impossibly difficult logistics of actually filming it, that too eluded us.

Having made thirteen more feature films since, I have to say that Bugsy Malone is not a film I would dare to attempt now. Francis Coppola, a few years after he first saw the film, reassured me that I wasn’t a complete lunatic: “Alan, when we (filmmakers) know nothing, at the outset of our careers, our naïveté sometimes forces us do fresh and original work, crazy as it might seem in hindsight.”

There’s a saying that “hindsight come with 20/20 vision”, so I hope I can remember how this curious film came about.

Before Bugsy Malone was a film it was just a story. In 1974 I had four small children and to keep them occupied on long (and mostly boring) car journeys, I would invent a story for them. It was a world of gangsters and showgirls set in New York City, a long time ago, and a long way from where we lived. On my eldest son Alex’s insistence, it was peopled with kids, just like the four of them sitting in the back of the car.

It would be a year or so before this family game came to fruition as a screenplay. At the time, I had been happily and successfully directing commercials and had managed to write the screenplay for David Puttnam’s first film, Melody. I had also had some success with a film I had made for the BBC, The Evacuees (1974), written by Jack Rosenthal and which eventually won a BAFTA and an Emmy. However, any notions of a feature film career were distracted by our busy commercials business and a less than active (and, to be honest, completely disinterested) British film industry.

Most of the scripts I had written at the time seemed to be returned to me each time with almost a rubber stamp on them saying: “too parochial,” and “too English.” In the crippled British film industry of 1974, this meant “nothing doing”. Undaunted, and for totally pragmatic reasons, I therefore began writing my “American script.” I have to say that I was not alone in this, egged on as I was by my stalwart producer and TV commercials partner, Alan Marshall, who, as always, was chief cheerleader in those dark days of discouragement. To be honest, my script for Bugsy Malone was not so much about “America” as about “American movies.” At the time, I had little first hand knowledge of the United States – apart from a few ‘smash and grab’ trips to New York to shoot Alka-Seltzer commercials – but mostly I knew American movies. My script was a cinematic pastiche, after all, with echoes and references to Astaire, Kelly, Cagney, Brando and Welles. (To be candid, giant jigsaw puzzles aside, it’s more Mack Sennett than Orson Welles. It’s not so much an homage as a basket full of fond memories of double bills at the flea-pit Blue Hall re-run cinema in Upper Street Islington, that I had devoured as a kid.)

I then touted my script around. This didn’t take too long as there were only two places that financed films in 1974, Rank and EMI, whose offices were situated at either end of Wardour Street. My sales pitch was met with less than enthusiasm. (Stunned silence might be a better description.) “It’s a fusion of two genres – the Hollywood musical and the gangster film,” I would enthuse. “Oh [cough], and it will have a cast entirely of kids, average age twelve.” Needless to say, we were always politely shown the door. We continued anyway, at Alan Marshall’s insistence. “What do those Wardour Street dandruffed, fuck-pigs know anyway?” he would wisely mutter as we as we hit the fresh air and the Wardour Street pavement. (Actually his vocabulary was a good deal more colourful, but possibly not appropriate for reproduction here.)

I then touted my script around. This didn’t take too long as there were only two places that financed films in 1974, Rank and EMI, whose offices were situated at either end of Wardour Street. My sales pitch was met with less than enthusiasm. (Stunned silence might be a better description.) “It’s a fusion of two genres – the Hollywood musical and the gangster film,” I would enthuse. “Oh [cough], and it will have a cast entirely of kids, average age twelve.” Needless to say, we were always politely shown the door. We continued anyway, at Alan Marshall’s insistence. “What do those Wardour Street dandruffed, fuck-pigs know anyway?” he would wisely mutter as we as we hit the fresh air and the Wardour Street pavement. (Actually his vocabulary was a good deal more colourful, but possibly not appropriate for reproduction here.)

Our financial independence, courtesy of TV commercials, allowed us to prepare the film for a whole year with not a sniff of interest (nor a penny) from the traditional film financiers. We first set out to see if we could actually cast it at the level I had envisioned. I subsequently visited every American Air Force base in Britain, lugging one of the first Sony portable video recorders. “Portable” is not a very accurate description, as it weighed a ton and lugging it from classroom to classroom, supported by it’s re-enforced shoulder strap, resulted in a double hernia.

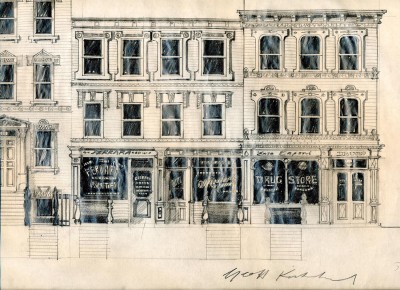

Geoffrey Kirkland, my production designer, began drawing up sets and costume designer Monica Howe began scouring markets all over the country looking for period costumes. All of these costumes would then have to be subsequently cut down to size for of our diminutive cast.

At this point, my friend David Puttnam came into the picture. We had originally tried to go it alone without his help, but now we needed his special talents and contacts to make things happen. Whether he was impressed by our fiscally bold endeavours and industriousness, or just felt plain sorry for us, he will never tell. Puttnam was enjoying some success himself (That’ll Be the Day and Stardust) and was on his way to becoming one of Britain’s most significant film producers. Puttnam, canny operator that he was in dealing with the tricky world of film finance, promptly closed the deal on our film. Our budget was £1 million (half of which was promised from the Rank Organisation and half from the then government body, the National Film Finance Consortium). The catch was that the two financiers had a proviso that we first secure a U.S. distributor. (Rank would distribute in the U.K., Australia, etc.) This was probably a way of avoiding making the film at all because ensnaring an American distributor for such an eccentric and risky project was thought to be near on impossible. If anyone in the US did bite however, it would give the necessary courage to the suits in Wardour street and Soho Square to take a punt.

Puttnam and I dutifully flew to Los Angeles. As fate would have it, Richard Sylbert, the great America production designer (Chinatown, The Graduate, The Pawnbroker) was fortuitously (if rather surprisingly) doing a short stint as a studio executive at Paramount. Unlike the programmed, button-downed executives we normally encountered, he was rather taken by our unorthodox, mostly visual presentation (we came from advertising, remember) and to everyone’s surprise a deal was struck for U.S. distribution (albeit for a small amount of money and at no great risk to Paramount.). We were on our way.

I had arrived in L.A. in advance of Puttnam and had been advised by the agent Robert Littman (a longtime Brit in L.A.) to go straight from the airport to a screening he had set up at 20th Century Fox Studios which in those pre-Star Wars, pre-Murdoch days, still had the rusting Hello Dolly set as you drove in. The rest of the once majestic studio was an unimpressive, pot-holed, industrial shit heap, the old lady suffering, like the rest of Hollywood, from years of neglect.

Robert wanted me to check out a young American actress who everyone was talking about. I sat on my own, suitcase at my side, in the shabby screening room with its threadbare carpets replete with Darryl F. Zanuck’s cigar burns in the mouldy leather armchairs that smelled of fish. The film was Echoes of Summer, and the young actress in question was Jodie Foster. I subsequently met with Jodie in Robert’s office. Affable and articulate, the twelve-year-old Jodie was wise beyond her years. Not exactly a newcomer, she had been in front of the cameras since she was three years old, starting with commercials. Jodie had also starred in the TV version of Paper Moon and had a small, but memorable, appearance in Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. She listened patiently as I described the film and reacted positively – she thought it sounded like fun to be surrounded by kids instead of adults for once. But at the time she was a tad more excited about her next job, playing a hooker with De Niro in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, which she was on her way to shoot in New York.

I then lugged my video camera all over, from dance schools in East Hollywood to parochial schools in Brooklyn, Harlem and the Bronx. In a Brooklyn Catholic school I found Fat Sam. My normal practice was to go into classrooms, and with the permission of the teachers, involve the kids in conversation about movies, etc. In one of the classes I asked them, “Who is the most badly behaved kid in the class?” Thirty kids pointed to one chubby little boy at the back of the room. “Cassisi!” they screamed in unison. John Cassisi, as modestly as he was able, put his hands up, palms out, smiled and nodded. He spoke in Italian, apparently agreeing with the class consensus. I took him off to a corner of the schoolyard and began to work with him. Although he had never acted before, he yelled out the lines from my script with gusto. He was a natural, and I knew right away that we had our Fat Sam.

Scott Baio, Bugsy

Back in Manhattan, I saw all the kids who had come through conventional routes with agents. Scott Baio came into one of these sessions. He had already done small parts in commercials. I loved his gravelly voice – still a child’s voice, but with the wonderful New York scraped tonsilled timbre that we needed to make our dialogue believable. In a Harlem dance school I found Alvin “Humpty” Johnson, who plays “Fizzy.” To be honest, he couldn’t dance very well, and reading the script was impossible for him, but he was a beautiful kid.

Returning to England, I zeroed in on finding the rest of the cast. Our casting adventure in the previous year had taken us all over the U.K. — firstly to American Air Force bases (We found Florrie Dugger [Blousey] at Chicksands Air Base in Oxfordshire where her father was a US Airforce pilot.) We also covered American schools in London, French schools, German schools, drama schools, boxing schools and dancing schools all over the country. We had attended and videotaped almost a hundred school Christmas shows. In all, we saw almost 10,000 kids — the shortlist alone amounted to 20 hours of videotapes, which I whittled down to the 200 young cast who made it to the finished film.

The final auditions for the dance parts were held in London and Leeds. Only nine girls could make it to the “speakeasy chorus” and Alan Marshall had the unenviable task of telling the unsuccessful candidates —worse still, their mothers — that they hadn’t made it. The speakeasy band was made up of members of the British National Youth Jazz Orchestra, which brings me to the music.

Originally, to sell my script, I had written an outline of lyrics to nonexistent songs to demonstrate how they could further the narrative. Alan Marshall, David Puttnam and I explored many avenues with regard to composers and we were drawing a blank. (These were less than stellar times for British music. In 1974-75 the record charts included everything from Telly Savalas and Serge Gainsbourg to Suzi Quatro and Gary Glitter.) I wanted a 1920’s sound but with a modern feel to make it a little more palatable to an audience more in tune with Alvin Stardust than Rodgers & Hart. Finally, in frustration, David Puttnam said to me, “Well, who do you like?” I replied, “My personal favourite is Paul Williams, but you’ll never get him.” Puttnam stormed out of the room, picked up the phone and a week later I was on a plane to Las Vegas to meet with Paul.

Apart from the success of his own albums, Paul’s songs had been recorded by a diverse group of artists from the Carpenters to Sinatra and Streisand. Paul was performing at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas and our first meetings were in between his twice-nightly shows as we talked about the story and the characters. “Talk” is not quite the right word, as Paul would croak in a low whisper to save his voice for the late show. Needless to say, in two nights we hadn’t got very far. By the third day we decided to have lunch in a place off the strip called “Fox’s Deli.” For nearly four hours, in between Paul signing autographs and the waitress spilling coffee on my script, we went through the story, line-by-line, character-by-character and song-by-song. Paul had a remarkable facility for humming a melody the moment I mentioned a phrase or a situation, and I was anxious that he might forget them. But he is blessed with a tape recorder locked away somewhere inside his head. After consuming a mountain of deli sandwiches and a great deal of Coors beer later, we had the structure and basic score for our movie. Six weeks later our cast were rehearsing the finished songs on Pinewood’s ‘H’ stage.

Production Designer Geoffrey Kirkland’s set drawing for main street

Our financial deal with Rank called for us to shoot at Pinewood Studios, which they owned (they were handing it out with one hand and raking it in with the other) and where Geoffrey Kirkland had begun to build our sets. Our giant New York street complex had to be built inside Pinewood’s biggest sound stage because the script called for many night scenes and British child labour laws severely limited the number of hours our kids would be allowed to film at night. Consequently we built the street indoors so that we could light it for night, but shoot during the day. Geoffrey Kirkland and I had walked the Lower East Side in Manhattan, measuring up and taking photographs. The entire street set, slightly scaled down, was built-up on three-foot platforms to allow for basements and to accommodate subterranean pipes that gushed steam from the manholes. Over 80 tons of concrete were poured to form the cobbled streets. Needless to say, such a mammoth undertaking took its toll on our budget and Alan Marshall and I were forced back into making a few more TV commercials to pay for the extra costs (amounting to one side of our street).

Costume Designer, Monica Howe, with an army of seamstresses, had spent months scouring flea markets, designing and adapting the 500 miniature period-correct costumes used in the film.

The paperwork needed to allow the 200 cast to work was mountainous, as production coordinator Valerie Craig (who had been with Alan Marshall and myself since the beginning of our company) dealt with 33 local councils for the kids’ licenses to work and for medical approvals, not to mention organizing the UK access for children I had cast in New York and Los Angeles.

Jodie arrived from New York with her poorly bleached, ‘big hair’ Taxi Driver hairdo. Sarah Monzani, in charge of our make up and hair, artfully fashioned it into Tallulah’s immaculate 1920’s coif — although Jodie didn’t think it was too artful at the time and cried as Sarah snipped away and wielded the hot tongs, as Jodie’s mother Brandy, banged on the locked make-up room door to stop the torture..

True to the period, the boys also had to suffer some pretty severe haircuts, especially Dexter Fletcher (“Babyface”) who was so devastated by the embarrassment of his painfully severe “pudding basin” chop, that his mother insisted that the production supply him with a wig to wear to school. I was put under great pressure by the kids to cut my own hair (which was shoulder-length at the time) as a gesture of solidarity as their ample locks hit the floor. (I managed to side step that one.)

Track by track, the music would gradually arrive from Paul Williams in the States. He was on tour at the time and as he and his band stopped in each new city, they would find a recording studio and dutifully send us the resultant tapes of the completed music. Our deadline meant that we took what we were sent —piecemeal—frankly there was no time to rework anything. The kids would receive their songs and walk around Pinewood, wearing their Walkman earphones, mouthing and learning their lip synch. Jodie was particularly puzzled when Tallulah’s song arrived, the register of the singer’s voice being much higher than her own speaking voice. I think Jodie was expecting a sort of sultry Marlene Dietrich voice to match the timbre of her own quite dark voice and, instead, a high pitched Betty Boop number arrived which came in for a lot of teasing from the other kids. The same thing happened with Scott’s ‘Down and Out’ song, only this time in reverse. The more mature voice arrived which didn’t match Scott’s own voice — still on the cusp of breaking. As we were just days away from filming, I had to admit that panic was setting in. “What do I do?” I said to David Puttnam and Alan Marshall, my producers. “Just get on with it,” replied Alan Marshall, pragmatic as ever.

‘Humpty’ Albin Jenkins, Fizzy

Watching the film after all these years, this is still one aspect that I find the most bizarre. Adult voices coming out of these kids’ mouths? Considering the sedulous approach to our subsequent musical films, the whole process on Bugsy was pretty rudimentary — everything was done on the hoof. I had told Paul that I didn’t want squeaky kids voices and he interpreted this in his own way. But curiously people seem to have accepted this anomaly over the years. It’s bizarre, but the whole film is full of ridiculous notions anyway. So why not one more?

Gillian Gregory, the choreographer (Tommy, The Boyfriend) had barely six weeks to put her routines into practice and, with greater difficulty, had to teach the non-dancers how to move. We took over the local Holiday Inn, which became an enormous dormitory for the entire cast. Johnny Cassisi was soon dubbed “the scourge of Pinewood” — not to mention the Holiday Inn after hours. Each day Jodie would regale me with stories of the previous night’s shenanigans as the cast broke their strict curfew: chaperones chasing Johnny Cassisi, chasing dancers, who were chasing boys chasing exhausted assistant directors. Mack Sennett indeed. (The activities at the Holiday Inn alone would have made an interesting movie of its own.) Production Manager, Garth Thomas (a very large man) bravely, if vainly, policed the corridors with a flashlight and a rolled-up newspaper. Everybody had a crush on the handsome Scott Baio and there were many broken hearts left behind when he returned to new York. Jodie confided in me, “I kissed him once, really late at night. About 8p.m. Garth Thomas’s curfew was obviously strictly enforced.

Jodie Foster, Tallulah

Our six weeks of rehearsals allowed for the young cast to get the feel of a film studio – running riot as they did on the Pinewood back lot. It also afforded me the opportunity to work with the kids one on one and to juggle the cast as their strengths and weaknesses became apparent. (During this musical chairs process, Florrie Dugger was slid across from a smaller part to the principal role of Blousey.) Not that everything went smoothly. There was a considerable divide between the kids from America and the kids from the air bases in England. Add to that the tough kids from London, Liverpool, Manchester and Leeds and the Pinewood back lot often resembled a battlefield. The other film shooting at the studio at the time was Brian Forbes’ remake of Cinderella. Their genteel cast in their corsets and crinolines were somewhat perplexed, terrorized as they often were in the Pinewood corridors by our boisterous, pubescent thugs masquerading as actors.

On set we had much stricter rules. I had said from the beginning that this wasn’t just a “kids’ film” and so I treated the young cast like adults and expected them to behave accordingly. Ironically, unlike many adult actors, everyone was always word-perfect with their lines.Perhaps they didn’t hit their marks with the regularity of grown-up actors, but there again, we didn’t get grown-up tantrums either. The film is a charade, and so I encouraged improvisation and spontaneity, but not at the expense of the written lines. Jodie was impeccable as ever and extremely “set savvy.” I think she directed me as much as I directed her. She was extremely knowledgeable of the filmmaking process —she could have complicated technical conversations with the camera crew and script supervisor that were beyond her years. Even then, when she was twelve, I joked that if I got sick she could take over. On the other hand it was humbling and, I think quite fun, for her to be with a cast of all kids. Normally she was the only (very smart) kid amongst adults. Jodie had spent her entire childhood on a film set and she had arrived from New York where she’d been acting with Robert De Niro and Harvey Keitel no less, and was suddenly just a kid thrust amongst 200 other kids — and not one of them had ever heard of Robert De Niro.

We had planned to film through as much of the summer (of 1975) as possible, taking advantage of the summer holidays, but as our shooting schedule and rehearsals called for a much longer period we had to set up a full-time school at the studio. We had six teachers who had to adapt to different teaching methods and levels in the U.K. and U.S. and a five-year age span between the kids. The child labour laws regarding filming are quite strict, and our high profile meant that the local welfare officer was there every day, lurking with his clipboard and stopwatch, making sure that each kid had his or her requisite rest and learning periods in between the time spent “under the lights”. To this end we evolved a system of preparing two sets simultaneously, so that I could rest some of the young actors, whilst working with others and consequently shoot continuously, without any down-time for the crew.

Feeding the hungry cast.

Illustration by Arthur Robins

To feed them, the studio kitchens churned out a mountain of hamburgers— the Pinewood canteen becoming the biggest hamburger restaurant between London and Birmingham!

Alan Marshall and I had assembled a crew that had largely worked with us before on commercials. There are two cinematographers credited (‘lighting cameramen’, as they were humbly called in 1975): Michael Seresin and Peter Biziou. Michael had been set to do the film but had run over on another film that he was shooting in France. Peter Bizou graciously stepped in and shot the first two weeks (mostly the difficult night scenes on our giant street set) until Michael finally arrived and Peter handed over the light meter. Both have worked on my films since (Michael did Midnight Express, Fame, Shoot the Moon, Birdy, Angel Heart, Come See the Paradise, Angela’s Ashes, and most recently The Life of David Gale. Peter did Pink Floyd The Wall and The Road to Wellville and Mississippi Burning, for which he won the Academy Award®.)

Pinewood Studios at the time had been rather neglected by the owners, Rank. So poorly was the Rank Organization run that it was suggested that the company stopped shooting films and started to shoot the Board of Directors. The studio, like the company, was on its last legs run into the ground by a cabal of atavistic Union bullies and bureaucratic freemasons. The restaurant —the old oak paneled ball room of the original manor house — was full of minicab drivers and Slough businessmen taking their secretaries to lunch in the faint hope of a glimpse of someone remotely famous. At the top table sat the Rank apparatchiks looking out at the rest of us hoypolloi like the dignitaries Oliver Twist’s workhouse. Whilst rehearsing one week-end I got greatest of puerile pleasures in gaffer taping a Camembert cheese to the underside of their dining table which stunk for weeks — not that they noticed.

The studio lot was a shanty town of tin huts that housed small lease holders. The small special effects company that we had employed were located in a nest of these corrugated roofed buildings and with limited resources, commensurate with our meager budget, they embarked on the difficult ballistic challenge of “the splurge gun”. With the obvious logic that a gangster story needed guns but a kids’ film didn’t, I had envisaged a projectile version of the silent movies’ custard pie. The original models were powered by compressed air and fired a missile of cream encapsulated in a sphere of wax. Needless to say, with the greatest of efforts, and hours of experimentation, they never really worked as well as we had hoped. The cream projectiles, in order to survive the considerable impact of the gun, necessitated a thick wax pellet that could cause serious discomfort to the recipient. (I know this from experience, as Alan Marshall and I were the original guinea pigs for the prototype gun. We both survived the early tests, being smacked in the face by missiles that felt more like golf balls than benign puffs of cream. We were both walking around with a red splodge on our foreheads for weeks afterwards.) This was obviously a non-starter with our young cast.

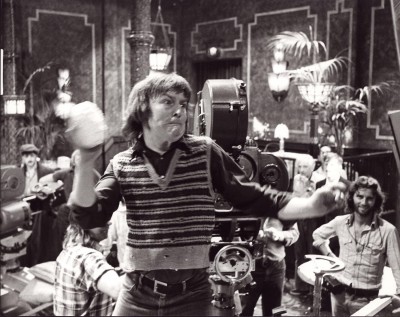

Alan Parker throws pie as Michael Seresin watches, Pinewood Studios

True to the well worn adage that “necessity is the mother of invention,” it has to be admitted that what is seen on screen is mostly an illusion. The guns fired ping-pong balls and what actually arrives on their targets, thanks to the magic of Gerry Hambling’s editing, is a dollop of whipped cream, usually thrown by myself or the prop man. We had started off with shaving cream but it smarted the eyes, so we ended up with doughnut cream. After 70 days of filming, over a thousand custard pies were thrown and we got through 100 gallons of artificial cream.

We also experimented with our innovative, if somewhat impractical, “bike-mobiles” – hand-crafted, at great cost, they could achieve a respectable ten miles an hour. (Although, it has to be admitted, in the film they are generally being pushed by the assistant directors, carefully secreted away out of the shots.)

Almost all the filming was done at Pinewood Studios, with a few excursions to nearby Black Park and a disused biscuit factory in Reading (where we did the “Down and Out” scenes). We also filmed at the Richmond Theatre for our audition scenes. It was here that I introduced Bonnie Langford as the egregious Lena Marelli. Eleven year old Bonnie’s rather cloying, stagey over-confidence was the epitome of how I didn’t want the rest of the kids to behave. Bonnie had made her wonderfully precocious West End debut aged eight in 1972 in the stage musical of ‘Gone With the Wind’. When a horse “copiously unburdened” itself centre stage, Sir Noel Coward famously remarked,” If they’d have shoved the little girl up the horse’s arse, they’d have solved both problems.”

Our final scene was the final speakeasy ‘shoot out’ between the two gangs. The rich brown set, ehanced by Michael Seresin’s juicy lighting, was turned into a snow-scape by the entire cast in a frenzy of custard pies, splurge guns and flour bombs which destroyed the set in about thirty seconds flat. No one was left un-splurged —including the the film crew. As Jodie Foster says, “So this is show business?”

Filming was completed in 70 days and we began the editing process with my editor Gerry Hambling (who subsequently edited a dozen more of my films) skillfully cutting together the multiple takes and thousands of feet of film. The final sound mix, also done at Pinewood, was somewhat restricted in that the music tapes that had arrived from Paul were in a crude rather simple two-track format. This was a far cry from the 72 tracks of my subsequent films.

By May of 1976 we were ready for our first public screenings: in competition at the Cannes Film Festival.

Afterwards

Looking at the film once more, after nearly thirty years, I am astonished at the lunacy and eccentricity of the original idea. Frankly, it was a miracle that it ever got made, for which I have to thank the producers, Alan Marshall and David Puttnam for their tenacity and support. Each Christmas, as it gets an airing on TV, I always have ambivalent feelings of pride and embarrassment as it has little in common with my thirteen films that followed.

When we finished the film it was offered to the Cannes Film Festival as the official British entry. At first, they turned it down for not being “esoteric” enough for the festival. However, Puttnam’s will prevailed and it was eventually included in the festival. Although we didn’t have a prayer of winning, we did get a respectable ovation. Certainly, Bugsy Malone is not esoteric, but no one could say that it isn’t original and Cassissi, Jodie and myself were suddenly treated like pop stars—which lasted a good couple of hours or so before everyone forgot about us. For all of us it was our first dose of the zany capriciousness of Cannes. The guest of honour at the after-screening party was the great Sir Michael Balcon, who was extremely flattering about the film which, for Puttnam, Marshall and myself, made all the madness worthwile.

The film was nominated for eight BAFTA awards and won five. The music was also nominated for an Oscar® and Golden Globe.

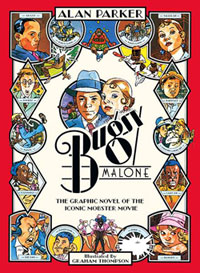

I had written a couple of chapters of the book before the film started and completed it after the film was finished. I wrote a special pared down theatrical version to perform in schools and have always been gratified by the hundreds of amateur versions that have been mounted over the years – providing parts for almost every kid, whatever their particular talents or ethnic background. We even did a graphic novel version, long before they were fashionable.

Jodie went on to be the youngest actress ever to win two Oscars (The Accused and Silence of the Lambs) and, as could have been predicted in 1975, a pretty good director in her own right. Scott starred in TV’s Happy Days, Joanie Loves Chechi and Charles in Charge. John Cassissi, after trying his luck in Hollywood, returned to the “construction business” building skyscrapers in Manahattan.

At the end of shooting I asked Florrie Dugger if she would like to do more acting. “Nah, I want to be a nurse. Kind of corny I guess, but at least you don’t have to spend an hour every morning getting your hair fixed.” True to her word , Florrie went on to serve 21 years in the US Medical Corps. Married to a flyer she still lives on an air-base — just as she did when I first auditioned her as a child in England.

Other young actors like Dexter Fletcher and Phil Daniels went on to forge successful acting careers.

Martin Lev (Dandy Dan) was, at 16, one of the oldest in the cast. He, like Jodie, had done a lot of work previously with adults (at the Royal Shakespeare Compnay) and at the time, probably found it difficult to be surrounded by so many wacky, uninhibited kids. He eventually gave up acting to become a designer. Sadly he contracted ME and, aged 32, committed suicide.

When we made Bugsy Malone, it never occurred to us that we were attempting the absurd. It was daring and brave, except we were all too ingenuous to know it at the time. Most importantly, it was a labour of love by a lot of people making their first film and probably, in its own curious and bizarre way, its why this daft film works.

As Razamataz and the speakeasy crowd sing in the final scene: you give a little love and it all comes back to you.

(Written to accompany the new DVD release of Bugsy Malone. )

Bugsy Malone Graphic Novel, republished by HarperCollins, November, 2013

Also a version of the above appeared in The Telegraph on republication of the novel by HarperCollins as part of their Essential Modern Classics list, November 2011.

THE GRAPHIC NOVEL OF BUGSY MALONE is to be republished by HarperCollins, November, 2013

Text © Alan Parker. All photos © National Film Trustee Corporation. Stills photography: David Appleby. Cinematographers: Michael Seresin, Peter Biziou