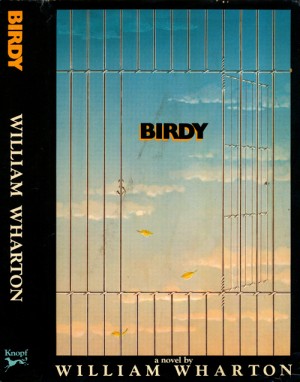

BIRDY

The making of the film, egg by egg.

I was first sent the galley proofs of William Wharton’s novel in 1978 with the usual note from my agent saying, “Must act quickly, book will be optioned.” And soon it was, and not by us.

My next encounter with the project was in 1983. I was still enjoying what is pretentiously called a sabbatical – basically I was knackered from shooting Fame, Pink Floyd The Wall and Shoot the Moon in quick succession and I had taken a year off. Birdy, the hot novel of 1978 had cooled off somewhat in 1983 and the option had been picked up by A&M Records film division. I always thought that because they were a record company their tastes were possibly a little offbeat and maybe they saw things in it that the mainstream film studios, forever buttoned-up in their commercial straightjackets, hadn’t. Sandy Kroopf and Jack Behr, two Los Angeles based writers, had been commissioned to write the screenplay. Their script was sent to me early in 1983 and I immediately liked what they had done. They had minimized the internalization inside Birdy’s head and cunningly interwoven the past and present. The “one person” schizophrenia of the book had been clearly defined for easier cinematic narrative, which made the story very obviously the friendship between two boys. They also moved the story forward so that it was more relevant to our times, and now hinged on the horror of Vietnam rather than World War II.

My next encounter with the project was in 1983. I was still enjoying what is pretentiously called a sabbatical – basically I was knackered from shooting Fame, Pink Floyd The Wall and Shoot the Moon in quick succession and I had taken a year off. Birdy, the hot novel of 1978 had cooled off somewhat in 1983 and the option had been picked up by A&M Records film division. I always thought that because they were a record company their tastes were possibly a little offbeat and maybe they saw things in it that the mainstream film studios, forever buttoned-up in their commercial straightjackets, hadn’t. Sandy Kroopf and Jack Behr, two Los Angeles based writers, had been commissioned to write the screenplay. Their script was sent to me early in 1983 and I immediately liked what they had done. They had minimized the internalization inside Birdy’s head and cunningly interwoven the past and present. The “one person” schizophrenia of the book had been clearly defined for easier cinematic narrative, which made the story very obviously the friendship between two boys. They also moved the story forward so that it was more relevant to our times, and now hinged on the horror of Vietnam rather than World War II.

Coincidentally, I had talked with Tri-Star Pictures, a newly formed ‘major’ studio about the possibility of doing a film with their nascent company and they agreed to take on the project and I duly went off to Los Angeles to work with Sandy and Jack on the screenplay. Writers are always suspicious of directors who also write but the collaboration was friendly and fruitful as we tugged, stretched and juggled the script closer to the film we wanted to make.

Logistically, the film took itself in various directions. On reading the book, the descriptive passages reminded me of the working class terraced streets of North London, where I grew up, three thousand miles away from Billy Penn’s statue on top of Philadelphia’s City Hall. Originally I had thought of filming in the run-down areas of Oakland, but one visit to the Philadelphia of the book convinced me that, unique that it is, it would be more truthful to Wharton’s story. The row upon row of derelict houses, acre upon acre of urban decay sprawled across this once beautiful city were a perverse seduction to us: a background of hopelessness that anyone would yearn to soar above.

As with most American cities these days, the Mayor’s office had a ‘Motion Picture Department’ ostensibly to facilitate filming in order to coax away Hollywood’s celluloid dollars. Everyone at City Hall was extremely cooperative but, in truth, ultimately quite ineffectual in helping us combat the realities of the Philadelphia streets. Our script called for 24 different locations but our priority was finding Birdy’s house and immediate environ. Of the thousands of empty houses and broken down streets that seemed perfect on our first visit, none gave us the perfect geometry of Birdy’s house, street, backyard, and baseball pitch that our story required. Geoffrey Kirkland, the Production designer, gradually mapped out the city, block by block, offering me suggestions on my weekend visits from New York where I was casting. Weeks went by: but however sedulous their searches, it proved more difficult than we thought. More often than not, the boarded up houses were occupied by squatters: an invisible army of homeless that no official would admit existed, but nonetheless were ready to defend their homes when we pried beyond the corrugated iron. “You from the police? A film company? Go —-yourselves.”

Fortunately, half the film would be shot in Northern California, which added a little sunshine to those miserable December days tramping around the slush of Philly looking for film sets amongst the rubble that the locals called home. We decided to base the film in the San Francisco area as the Agnew’s Mental Hospital in San Jose was to be a significant part of our filming and we had become comfortable filming in the area since Shoot the Moon. I liked the local technicians and the Bay area had become our ‘home away from home’ – and, more pragmatically, the local union was amenable to the import of my British cinematographer Michael Seresin, operator Mike Roberts and editor, Gerry Hambling.

At Agnew’s Hospital, we built the sets inside an actual building utilizing and adapting existing architecture in much the same way as we had done with SagmalVilar prison in Midnight Express. Much of the film took place inside Birdy’s cell and the camera would have to explore every crack and tile of this room which had to have a personality of its own: the strange buttresses and corners would become focuses for Birdy’s muted memories.

In Northern California we also found ‘Philadelphia’ locations for the garbage dump and gas-tanks. Also we would be filming our Vietnam locations in Modesto in California’s central valley. The entire area had been flooded and in the five times that I visited, the water table dropped, making it difficult to pin point locations. Although there was plenty of time before filming, tropical grass had to be planted and cultivated in the months ahead.

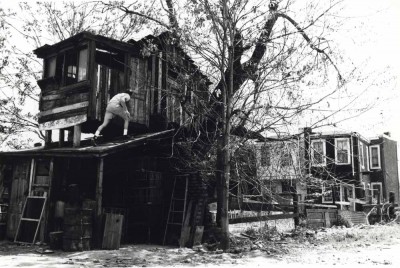

Back in Philadelphia, we found Birdy’s house and backyard and made plans to transform an open area between the streets into an improvised baseball diamond and waste ground. The narrow porched houses would give us the Irish\Italian community of the early 60’s while retaining much of the local color that Wharton had described in his book, which, of course, was set three decades before.

The elderly lady who lived in the ‘Birdy house’ for forty years seemed agreeable to the idea of a film crew descending upon her – until her relatives called in a lawyer and suddenly the required two months rent they suggested would have purchased the house three times over. We couldn’t afford to pay what they were asking so we looked for alternatives, when a bargain was struck, sending the elderly occupant on holiday to her sister in Georgia, whilst we loaned her house.

The Birdy ‘back-lot was a much bigger art direction task than first planned because of a factor that had crept into our reckonings, and served to plague us, in the weeks ahead. It was called ‘Sky-Cam’.

Garrett Brown, a brilliant camera engineer, had invented the ‘Steadicam’, which has become standard equipment on most movies. By a system of balances and gyros it could be strapped to an operator’s waist achieving perfectly smooth tracking shots without the need of a cumbersome wheeled dolly. We knew Garrett from ‘Fame’ where he had operated a remarkable continuous tracking shot in the New York subway for me. His latest invention, called the Sky-Cam’ had consumed most of his recent years and most of his cash. This system immediately became attractive to me because, in the film, I needed to show Birdy’s point of view as his imagination took flight. No one had ever achieved this before and we were to be the first. “We’re the guinea pigs,” I said to Alan Marshall. “Guinea pigs can’t fly,” he answered prophetically.

The revolutionary system consisted of four enormous posts (100 foot or more) from which were hung wires operated by motors controlled by a computer. At the central joining point of these four wires, hung a specially built lightweight Panavision camera.  A complicated system of gyros kept everything on an even keel. The possibility of joining in Birdy’s flight of fantasy was very exciting. I had devised a shot that swooped past the steeple of Birdy’s local church, across the waste ground strewn with junk, over the back yards, the baseball field, down Birdy’s street and finally up into the immense freedom of the sky.

A complicated system of gyros kept everything on an even keel. The possibility of joining in Birdy’s flight of fantasy was very exciting. I had devised a shot that swooped past the steeple of Birdy’s local church, across the waste ground strewn with junk, over the back yards, the baseball field, down Birdy’s street and finally up into the immense freedom of the sky.

Flying. Rising as if lifted from above. Through the whiteness. Into pure blue air.

This meant that an area covering a half square mile had to be built and dressed accurately to the 60’s period – a tall order, but worth it because Birdy’s “flight” was at the very heart of the piece and our chance to climb inside Birdy’s imagination.

And HIGHER. Up against the sky. Touching nowhere.

Funny isn’t it, all you need for poetry is a pencil. Movies, well, that’s something else.

I flew between the east and West coasts in search of locations and casting. Our searches took in Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, San Jose and Philadelphia. Looking for Birdy and Al was obviously our priority and I met with every possible young actor who could play the parts. We also had a number of ‘open calls’ – sometimes rather more descriptively called a cattle call”. “ In Philadelphia we saw over 2000 in one day each reading a few lines from the script, smiling for the Polaroid and being shown the back door. We went through the same process in San Francisco and New York.

In Philadelphia we found Rosanne played by a waitress in our local restaurant and Birdy’s Mum (Dolores Page) whose husband’s pigeons we had been admiring. Mr Sagessa, Mario, Mr. Kohler, Claire and Birdy’s Dad all walked in to our open calls.

Winnowing through our tapes I finally settled on Matthew Modine for Birdy. I had originally read the part of Al with him but his gentle, introverted honest quality seemed to say Birdy. He is a wonderful natural actor with an in-built phony-detector which makes it difficult for him to make a dishonest move. I had become tired of pseudo method-actor weirdoes bringing in stuffed pigeons and photos of dead relatives for motivation.

Nicolas Cage became my favorite for the outgoing Al very early on. The first time he came in to read for me he seemed so strong, so assured, that I was never sure if he could reveal the vulnerable side of his persona. The more he came in, the more he looked like Al who swaggered through life with big enough shoulders for the frail Birdy to lean on, but deep down, he needed Birdy more than Birdy needed him. Nicolas had changed his name from Coppola to Cage to avoid the professional inhibitions that he felt his famous Uncle’s name brought. Curiously, I never knew until after I’d cast him that he was Francis’s nephew.

Our start date had been set for May 15th (’84) having delayed production for six weeks in order for Matthew to finish Mrs. Soffel. This allowed us to sort out the unfathomable “Filthydelphia” (as it was affectionately dubbed by the Art Department), and for me to write my final shooting script, culling the last gems from the novel.

Alan Marshall had the unenviable task of negotiating with the local Philly unions who were notoriously difficult to deal with. There was, of course, to be a Teamster on every moving object, and some that didn’t move. The Vice-President of the Local who came to visit us still had a couple of bullets inside him from a past disagreement. We were told that the Teamster ‘captain’ on the film was to be the brother of the Teamster Local President.

I sold the car to a friend of my brother-in-law Nicky. You mess with that guy and you’ll wind up in a concrete shirt at the bottom of the Schuylkill River.

AL’S FATHER

Gary Gero, our animal trainer, had been working with the birds since January and we had eighty different canaries at various stages of “training”: Good lookers; good flyers; bell ringers and good hover-ers. The canaries, always skittish and neurotic, were frustratingly difficult to film at normal speeds. The main canary in the script “Perta” would eventually be played by a canary unromantically called ‘Bird No. 9’, but many of her ‘stunts’ were done by a less attractive, but more accomplished, bird called “Queepers”. We also had many birds sitting on eggs, hopefully to hatch out soon.

Matthew Modine and “Perta” played by “Bird No 9”

As well as the canaries, Gary was also training pigeons, a tropical hornbill, a cat, eighteen dogs and a seagull – all of which had their moments on screen.

By May 8th we were a week off the start of principal photography. It would have been nice to have had a little more rehearsal time, but Nic, Matthew and I did manage to get a week together at the local Church Hall – a short walk from Birdy’s house, where we taped out Birdy’s hospital cell on the floor, There’s never enough time, so rehearsal periods on films can only be exploratory: the beginnings of understanding the parts, rather than polishing or evolving finished performances. I suppose the most important task was to determine a working relationship between the three of us, for the months ahead.

The first day of filming found us in Birdy’s street in the heart of West Philly. First days are always tough. You have the 100 different shots for the rest of the movie tucked away on some memory disk at the back of the brain and they keep rushing forward, out of time and place, as you make the first tentative steps on the journey. As I was told by a wise crew member on my first film, “It’s not unusual to be a day behind after the first day. “

The rest of the week saw us filming around Birdy’s yard and adjacent ballpark. Dolores Sage, who plays Birdy’s Mum, had never acted before and so much of my time was spent giving her the necessary confidence, coaxing her into what the script asked for, but allowing her to be herself – her wonderful Philly accent cutting through the air as she overcame her nerves.

Our second week found us in the house once more. Birdy had to wrestle with the cat, prying open its jaws to save Perta. This worked well, although the cat was naturally a little groggy after a number of takes. Unfortunately, we had a rare negative scratch on this day’s filming (not done by the cat) which meant it had to be done all over again. It always astonishes me how much technically can go wrong a film and how little usually does. Consequently I’m absurdly superstitious whilst filming, which was an omen for the next four days, because Sky-Cam was about to make its debut.

We had choreographed an entire area about a half square mile with kids playing street hockey, baseball, mothers with children, old men walking dogs, women chatting in back gardens, plus dozens of vehicles – and everything 60’s period correct.

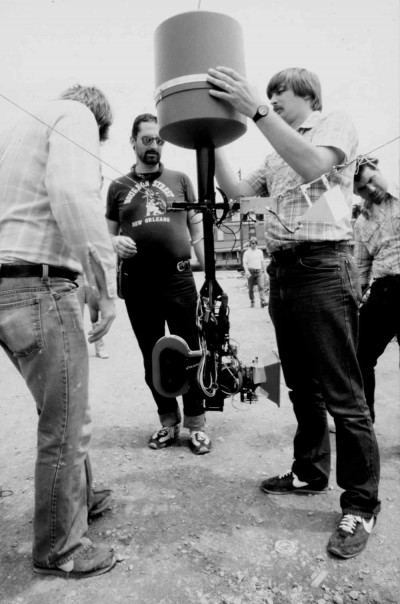

The Sky-Cam hung on wires strung from four cranes, their arms pointed directly into the air. We had built a scale model to accurately work out our shots and had lopped six feet off all local trees and telegraph poles. Our faith was absolute, our pioneering zeal knew no bounds. First, it rained, fouling the motors that controlled the guide wires. We lost a day watching the scientists playing with our train set. There was an enormous amount of press interest in this Kitty Hawk of cameras. Phrases like ‘changes the entire dynamics of cinema” and other codswollop rolled from my lips as we drank coffee in the rain waiting for the thing to fly. “Wouldn’t it be easier to buy 20 Eymos (a cheap camera) and get a shot putter to toss them in the air?” one journalist quipped. We all laughed nervously, trying not to let on to the probable wisdom of his remark.

The Sky-Cams control consul had conventional wheel handles that our operator could use to change direction of the lens whilst looking at a small monitor. Another guy – the Sky-Cam “flyer”, operated a computer on a joystick, much the same way you would fly a model aeroplane. By the end of the second day the boffins finally got it to fly. The shot I wanted was to observe kids playing near a burned-out car, from above – drop like a stone and then skim along the junk-yard, three feet from the ground, rise above the fence observe the baseball game and move up against the sky. On the first take, miraculously, it worked, except I wanted it faster. The second take looked wonderful as it swooped downwards, except suddenly the monitors went blank. The Sky-Cam had over-ridden its computer and smashed into the ground.

Through the whiteness.

Into pure Blue air. And higher. Up against the sky.

Touching nowhere.

Well, touching somewhere. Mainly the ground. Our Camera Assistant summed it up, as the machine bounced across the waste ground, he said, “Well, It’ll never work as a shovel.” The crew had dubbed the Sky-Cam the Kamikaze-cam as the patched up camera then hit a tree it was supposed to hop over, smashing the shutter and the hopes of any more filming. The Sky-Cam operator collapsed in tears.

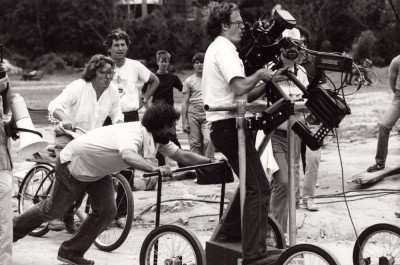

Skycam montage, Philadelphia

On such occasions you can’t scream and shout, you have to think on your feet. So far, we had only 40 seconds of screen-time in the can. Birdy had to fly and we had to fly with him. Consequently, we got out the trusty Steadicam and frantically began running down alleyways, across rubble, down streets – in a golf-cart and atop a bicycle dolly with me charging behind on a bike. We quickly built a ramp 20 feet high and 30 feet long to get the POV of the canary smashing into the window. Necessity is the mother of invention and the results are there to see on screen – as much due to Gerry Hambling’s editing and Peter Gabriel’s music as to our enterprise.

Alan Parker (on bike) with the Steadicam mounted on an improvised dolly.

It seemed like there wasn’t an easy shot in the film as we were always juggling variables outside the actors’ performances – be they the nerve shredding difficulties of filming the birds, or the danger of shooting high up, perched on narrow girders, underneath the elevated railway with live trains thundering passed, four feet from our heads.

One of the handicaps I had been working under, I have to confess, was that I didn’t like birds very much. One at a time is OK but in the scene of Mrs. Provost’s porch aviary there were 150 of the things. I started directing everyone, standing on a ladder in the rain, outside the porch using a megaphone to be heard through the glass. It was hopeless and I had to brave the aviary and the grisly sight of Mr. Tate blowing up the show-pigeon with his mouth as if it was a party balloon.

I also did a scene with another bird owner – a lovely character in the book called Mr. Lincoln – but I eventually cut this scene because the actor who played the part (Danny Glover of Lethal Weapon fame) couldn’t remember his lines.

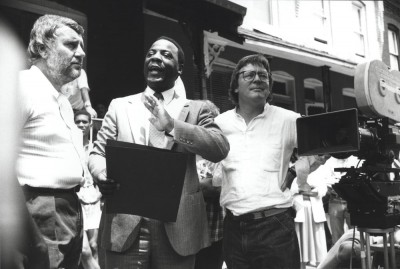

Director, Alan Parker, camera operator, Mike Roberts and a horse’s ass. Take your pick which is which.

The next week it was the dogs turn and a welcome break from canaries. For the slaughterhouse scenes we had borrowed dead horses from the local abattoir and the smell and flies were less than pleasant. I had cast real butchers who happily chopped away all day into the chunks of beef and goats’ carcasses quite unperturbed at our squeamishness. By the end of the day there were twenty more vegetarians on the crew.

The police had warned us off from filming in the tougher neighbourhoods of North Philly. But that was where we’d found the streets we needed. During a local TV interview I had mentioned that our experiences of working in Philly had been less than enjoyable and so an alert P.R. person at City Hall promptly persuaded Mayor Wilson Goode, Philadelphia’s first black mayor, to pop along and present us with a “tribute plaque”. We stopped shooting whilst the mayor walked along the battered stoops and balconies, unctuously pressing the flesh, seasoned politician as he was. He then borrowed our megaphone and made a short speech, haranguing the local crowd, telling them to behave themselves and help these nice film people. He would have made a good Second assistant Director.

Producer, Alan Marshall, Mayor Wilson Goode and Alan Parker, Philadelphia

The new casinos and modern skyscrapers ruled out filming on the Atlantic City Boardwalk and so I settled on Wildwood, whose tacky charm hadn’t changed for forty years. Here the challenge was “Zimmy the Human Fish”. The gentleman who was playing it, a jeweler by profession, had been recruited at the local swimming pool and was thoroughly miserable as the poor guy held his breath, being nibbled at by a tank-full of fish.

It was time to fly to San Francisco for the second half of our filming.

You wanna fly? He’ll let you fly. He’s gonna send you air freight to some cage in a full time nut house.

AL

At Agnew’s mental Hospital in Santa Clara, we had built a replica of Birdy’s Philly bedroom in a makeshift studio in corner of Agnew’s Mental Hospital. Makeshift or not, it was a pleasure to return to a sane place of filming where the logistics and madness of a city didn’t dictate your every move.

Birdy’s flight from the top of the gas tanks was shot at a disused Gasworks at Hercules on the north shore of the Bay. Filming on a pitched corrugated roof 100 feet up was especially disconcerting to those of us fearful of heights. A director with a fear of birds and heights makes a film about flying? Our stuntmen rehearsed the fall onto the sand pile and we shot for what seemed like a bone-crunching number of times. I am always reluctant to shoot these things too many times, but the stuntmen are quite happy to, as they get “adjustments” to their pay each time they give their vertebrae a battering. As always, Matthew was fearless, but not Nicolas. “I’m in character.” He would weakly reply, whenever asked if he was scared hanging over the ledge, secured by the flimsiest of safety wires.

Nicolas Cage (Al) and Matthew Modine (Birdy) at Newby Island Garbage dump. San Jose.

The garbage dump where Birdy flies his ornithopter was outside San Jose, in a place rather romantically called “Newby Island”. We experimented with a 100-foot wire hanging from a helicopter to allow us to “fly” Birdy into a pond we’d constructed at the bottom of a hill of garbage. Originally we planned to land in a reservoir of water thirty yards further, but a test of the water had shown it to be hazardous to the actors’ health. Our wireman was an expert from Pinewood, who had developed his odd expertise in “flying” from working on the Superman films. I wanted the entire area strewn with garbage as far as the eye could see, which presented a few legal problems as open garbage should be covered after a few hours for health reasons. There was a gentle smell of methane gas given off from the solid mountain of waste we were standing on, which had us coughing for weeks afterwards.

Back at Agnew’s hospital, in the complex of cells, wards and corridors we had painted, aged down, damp patched, chipped and worn down to look as lived in as possible – we needed a set that could be shot from many angles, that always had layers, depths and textures, wherever the lens pointed. This was particularly so of Birdy’s cell – its somewhat eccentric architecture enabled us much scope to vary the staging (two handed scenes in a room being the most difficult to film and to keep visually interesting and cinematic – avoiding a succession talking heads). We had arranged to shoot sequentially to help Nicolas and Matthew with the development (or disintegration) of their characters. Nicolas had taken the biggest step of all in changing his personality. First, he had two teeth pulled, on either side of his jaw, to simulate shrapnel damage to his face. Second, he decided to wear his bandages continuously during these four weeks, on and off the set – a brave decision on his part as it impeded his eating not to mention his social life. But it helped him to sense the feelings Al might have had, imprisoned as he is behind the bandages. Each morning as fresh bandages were applied Nic would keep his eyes closed.

Back at Agnew’s hospital, in the complex of cells, wards and corridors we had painted, aged down, damp patched, chipped and worn down to look as lived in as possible – we needed a set that could be shot from many angles, that always had layers, depths and textures, wherever the lens pointed. This was particularly so of Birdy’s cell – its somewhat eccentric architecture enabled us much scope to vary the staging (two handed scenes in a room being the most difficult to film and to keep visually interesting and cinematic – avoiding a succession talking heads). We had arranged to shoot sequentially to help Nicolas and Matthew with the development (or disintegration) of their characters. Nicolas had taken the biggest step of all in changing his personality. First, he had two teeth pulled, on either side of his jaw, to simulate shrapnel damage to his face. Second, he decided to wear his bandages continuously during these four weeks, on and off the set – a brave decision on his part as it impeded his eating not to mention his social life. But it helped him to sense the feelings Al might have had, imprisoned as he is behind the bandages. Each morning as fresh bandages were applied Nic would keep his eyes closed.

I saw a guy at Fort Dix who had a face like a medium rare cheeseburger. I’m a little scared I won’t recognize who I’m shaving in the morning.

Al

Filming these hospital scenes was probably, dramatically, the most intense and satisfying of the whole shoot. Nicolas made things easy by being thoroughly prepared for his monologues and uncannily faithful to the text. Too often, young American actors use rambling improvisation as a smokescreen for not knowing their lines. Matthew had to play the mute foil to Al’s emotional outbursts. At the end of the day his crumpled body would be numb, as he patiently and silently reacted in a thousand different ways. Nicolas, as a person and an actor bore no resemblance to the cocky youth who swaggered through the streets of West Philadelphia, just a few weeks before. As we tackled the scenes in the cell, you could see Nic/Al’s vitality drain from him as it was transferred, almost sucked in, by Birdy. No director is sure how other directors direct. Each of us succeeds or fails in his or her own particular fashion. With Nicolas and Marthew I vacillated between the avuncular, the didactic and the demonic.

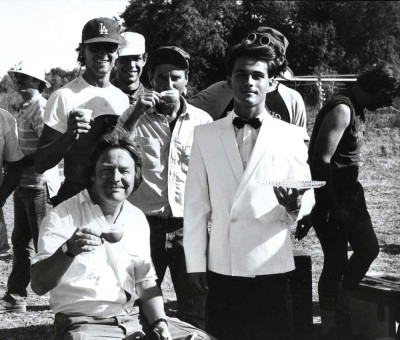

“Out of the smoke came a man wearing a white tuxedo and black bow tie, carrying a tray of cappuccinos.” Alan Parker, Michael Seresin and crew, Modesto, California

Our final lap of filming was in Modesto for the Vietnam sequences. We had helicopters and the full paraphernalia of real war, except we could stop for meal breaks and could re-do the explosions. For three months we had been planting tropical shrubbery, building our own napalmed forest, which Birdy would fly through in his escape from the horrors surrounding him. We painstakingly recreated a gruesome tableau of charred bodies surrounding Birdy’s crashed helicopter and our special effects crew laid on the charges for the fifteen 20gallon drums of gasoline that would simulate a napalm strike. We shot the explosion with four cameras and the heat from the blast was so great that the stage blood, liberally splashed on our “dead” extras began to boil. This was our last sequence accompanied by the usual demonstrations of relief and satisfaction. Out of the smoke came a man wearing a white tuxedo and black bow tie, carrying a tray of cappuccinos – the final gesture of the second assistant director at my continual complaints about the coffee. (1984 was pre-Starbucks!) I very much enjoyed making Birdy.

After the slog of my three previous films, particularly the last one, I had begun to wonder if film directing was the sort of thing a sane person should pursue. After Birdy, I feel my appetite for film has been renewed.

DR WEISS:

When we heard about your condition we thought it might be good therapy.

AL:

For Birdy, or for me?

The Music

Peter Gabriel was first suggested by Gil Friesen, the head of A&M Records. (Quite generous of him, as Peter was contracted to another label.)When I first met with Peter I had finished filming and had completed cutting about 60 minutes of the film. I had already experimented with his music by laying pieces culled from Peter’s solo albums – particularly the percussive rhythms which were unlike anything else you could find in contemporary music at the time. His music had a fresh and original edge: the unique rythms were an editors dream and at the same time his music had a mysterious presence that lingered long after the music had finished. .

I had called David Geffen (of Geffen Records) to ask if we could “borrow” Peter for the soundtrack music. Peter at the time was a little behind in delivering his new album (fortunately the wait was worth it as it turned out to be “So”). Geffen said ‘good luck’, but I’d never get the soundtrack in time to meet movie deadlines as Peter moves at his own pace.

Peter Gabriel, Alan Parker and sound mixer Bill Rowe, EMI studios, Elstree

However I had indicated to Peter pieces that would work well with the film, so we went back to his original 24 track masters and he played them individually, track by track, without the vocals at his studio at his home near Bath. The tracks were incredibly rich – dozens of layers of completely original sounds – many of which hadn’t been mixed into the previous albums – for me it was a treasure trove of unique sounds which Peter and Daniel Lanois re-mixed to serve individual scenes in the film. Or as Peter put on the front of the Birdy soundtrack album “Warning: This record contains recycled materials.”

Afterwards

Both Nicolas and Matthew went on to great success as actors. Birdy won the Grand Prix du Jury at the Cannes Film Festival. Sitting next to me in the audience was William Wharton who had flown down to the South of France from Paris, where he lived in a houseboat on the Seine. For many years there were absurdist rumours that he was in fact JD Salinger. I watched the film somewhat apprehensively wondering what he’d think of the film we’d made from his book.

Wharton’s real name is Albert Duaime. When he was a kid, he was called Al by his friends, but his family called him Bertie, or phonetically, “Birdy”. As the lights went up at the end of the movie, and after enjoying an extremely long and generous standing ovation, I turned to him. “So what do you think?”, “Oh, I liked it a lot. Except why did you make it two guys?”

All text © Alan Parker. All photos copyright Tristar Pictures, Inc. Stills photography: Ralph Nelson Jnr, Kerry Hayes. Cinematographer: Michael Seresin