Capital Punishment:

The Political Argument

Written to accompany the production notes on The Life of David Gale, November 2002Our film is a thriller. It would be hypocritical to pretend otherwise, cognizant as we all are of the commercial demands of the contemporary movie business. Perhaps, because of this alone, I still would have made the film. But I would also be remiss in pretending that this was the only reason that I was attracted to this project. Personally I am very much against the death penalty for several reasons, which I will explain below. Charles Randolph, the writer, is against it because he believes that it doesn’t work. The actors – principally Kevin, Kate and Laura -have varying views, which probably mirror the myriad of current popular opinions.

Nevertheless, our film is not a political diatribe. It is a story about people who would go to great extremes because of their beliefs, and to that end the film is biased on their behalf. However, I most certainly hope that the film will provoke debate. Here is my personal understanding of the “for” and “against” arguments with regard to the death penalty.

There are literally thousands of anti-death penalty web sites on the internet as patently pointed out by one of the few pro-death penalty sites.

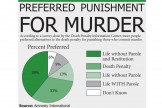

As of writing, the most recent U.S. survey (Gallup, May 2002) shows that 52% approve of the death penalty as opposed to 43% who favor “life without parole.” The “for” figure has grown steadily since an all time low in 1965, with a high in recent years of 61% (1997). When the question is asked without an alternative of life sentence, the figure in favor is a good deal higher.

Compassion for the victims of violent crime is paramount in all views on the death penalty, whether for or against it. A cursory glance at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s comprehensive web site revealing the actual crimes for which many of the residents of Death Row have been convicted makes for pretty gruesome reading. The most “bleeding heart” liberal could not argue with the litany of heinous crimes scrupulously recorded there. These people, if guilty of their crimes, undoubtedly should be punished. But should they be put to death? Because are they all guilty? In the last twenty-five years, 102 condemned prisoners were released from Death Row in the U.S. because they were discovered to be innocent. (A few due to the advent of DNA, but mostly they were victims of dishonest witnesses.)

The possibility of an innocent being executed is the single most important argument that could possibly sway public opinion (and hence is the crux of our movie). Of those polled by Gallup, 90% stated that they thought that probably as many as 10% of those executed were innocent. As the American Bar Association has repeatedly pointed out, individuals prosecuted for murder, predominantly from the bottom end of the economic scale, cannot afford to pay for lawyers and consequently, in the vast majority of cases, do not have adequate legal representation.

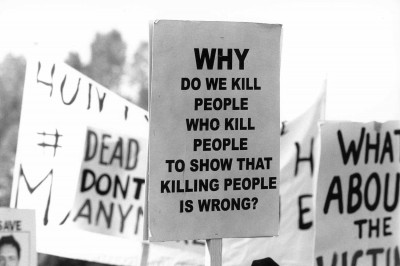

Popular support for the death penalty in the U.S. is linked to the considerable increase in violent crime. Little has to do with its effectiveness as a deterrent. The overwhelming evidence is to the contrary. (The Texas crime rate rose 4% in 2001, nearly five times the national average, with a 7.6% increase in homicides. At the same time, the total number of executions in Texas was more than three times that of any other state. The Northeast – the region with the lowest murder rate – had no executions in 2001.) There is also a view that the sheer brutalizing effect of the death penalty doesn’t deter, but actually aggravates crime. The polls state, however, that most people don’t even care if it is effective. The argument appears to still be fueled by retribution: that vindication is a moral imperative – that only execution can fulfill a society’s will – “it fits the crime.” To be against the death penalty becomes an expression of fear: of being “soft on crime,” or oblivious to the horrendous rise in crime, violent or otherwise, that affects everyone’s daily lives.

Popular support for the death penalty in the U.S. is linked to the considerable increase in violent crime. Little has to do with its effectiveness as a deterrent. The overwhelming evidence is to the contrary. (The Texas crime rate rose 4% in 2001, nearly five times the national average, with a 7.6% increase in homicides. At the same time, the total number of executions in Texas was more than three times that of any other state. The Northeast – the region with the lowest murder rate – had no executions in 2001.) There is also a view that the sheer brutalizing effect of the death penalty doesn’t deter, but actually aggravates crime. The polls state, however, that most people don’t even care if it is effective. The argument appears to still be fueled by retribution: that vindication is a moral imperative – that only execution can fulfill a society’s will – “it fits the crime.” To be against the death penalty becomes an expression of fear: of being “soft on crime,” or oblivious to the horrendous rise in crime, violent or otherwise, that affects everyone’s daily lives.

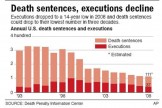

Since 1976, when the death penalty was reinstated in the United States, there have been 807 executions. In 2002 the figure (as I write) was 66 – down from a high of 98 in 1999. In theory, the death penalty exists in 38 states and Death Rows swell around the country (from 691 in 1980 to 3,697 currently). However, except for the southern states – led by Texas (285), Virginia (87), Missouri (58), and Florida (53) – many states seem reluctant to administer it. The view seemingly being that it’s important to have the death penalty as long as it’s rarely used. California, for instance (with the country’s highest number of homicides), has the most populous Death Row (613) and yet since 1976 has carried out only 10 executions.

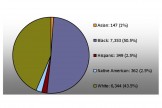

Another key issue in the debate is that of racial discrimination. While blacks represent 12% of the U.S. population, 35% of those executed are black. This is an issue that continues to divide the Supreme Court. As does the execution of juveniles and the mentally ill and retarded.

With regard to the “life without parole” solution, most people have a deep concern that this doesn’t actually mean “forever,” and that one day a murderer will be back on the streets. There is also the belief that this solution is too expensive – a waste of taxpayers’ money. (In fact, the cost of lifelong incarceration is actually one quarter of that incurred by a death penalty case – legally complex and with the state paying for both prosecution and defense costs. In Texas, the average time that a prisoner spends on Death Row is ten years while the legal appeals process takes place.)

The Supreme Court has also grappled with the issue of “cruel and unusual punishment” – the phrase contained in the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution (1791) taken from the English Bill of Rights (1689). The Supreme Court’s inability to come to an agreement on this led to the decade long moratorium on executions from the 1960’s into the 1970’s and the opinions of 1972 and 1976 when the Court, during a period of considerable obfuscation, declared the contrary decisions which have plagued the tenuous legality of the death penalty ever since. For example:

Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun: “Intravenous tubes attached to his arms will carry the instrument of death, a toxic fluid designed for the specific purpose of killing human beings…no longer a defendant…but a man, strapped to a gurney and seconds away from extinction.”

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, not known for his munificence (comparing lethal injection with the brutal rape and murder of an eleven-year-old girl): “How enviable a quiet death by lethal injection compared to that!”

Supreme Court Justice Blackmun: “The death penalty remains fraught with arbitrariness, discrimination, caprice, and mistake.”

Supreme Court Justice Scalia: “If the people conclude that more brutal deaths may be deterred by capital punishment, indeed, if they merely conclude that justice requires such brutal deaths to be avenged…the court’s Eighth Amendment jurisprudence should not prevent them.”

Apart from the shibboleth of deterrence, Justice Scalia probably got it right regarding public opinion: revenge is what it’s all about. Certainly lethal injection is a lot less “cruel and unusual” than “Old Sparky” – the electric chair, which preceded it for seventy years. You find the vein, a little choking, a sigh and they’re gone. Scalia has been at the center of the death penalty debate as a leading conservative on the Supreme Court since 1986, hence my attention to him here. For Scalia, retribution, not vengeance, is achieved, just as it says in the bible (which often figures in the debate – Matthew 5:7). Scalia quoting Paul: “If you do wrong, then you may well be afraid: because it is not for nothing that the symbol of authority is the sword.” Needless to say, Scalia, a Roman Catholic, wasn’t exactly in tune with his church, which had odd notions of “turning the other cheek” along with fifty other quotes from the bible not included here. In fact, the U.S. Catholic bishops had a go at influencing the Justice with Ezekiel: “And the Lord said, I swear I take no pleasure in taking the death of a wicked man.” Scalia was unimpressed by Ezekiel, because anyway, he wasn’t saying he took any pleasure in it, merely that he was “part of the machinery of death.” Pope John Paul II asked the U.S. to stop this “cycle of violence” to no avail. Scalia ignored them all in the name of American democracy. It wasn’t just the Pope who was worried about all the executions in the U.S. – so was the rest of the world. Not that it made a jot of difference to U.S. popular opinion. The U.S. suddenly found itself out of step with every modern democracy, all of whom had long before abolished the death penalty. Justice Scalia, however, had his own take on this. He said, “ The more Christian a country is, the less likely it is to regard the death penalty as immoral. Abolition has taken its firmest hold in post-Christian Europe and has best support in the church-going United States. I attribute this to the fact that for a believing Christian, death is no big deal.”

It goes without saying that Scalia’s characterization of Europe as “post-Christian” wouldn’t go down too well at the Vatican or with the European Union’s 254 million Catholics. Also, Scalia’s hypothesis doesn’t really fly, considering the conduct of atheist China and Muslim Iraq (the two countries that perform more executions than the United States). Although one could allow Scalia’s argument that both those countries do not consider death “a big deal.” In April, 2001, the United Nations passed a resolution calling for all members to abandon the death penalty. (Currently, 110 countries have already done so.) The U.S. was subsequently ejected from the U.N. Human Rights Committee for the first time since 1947, when the organization was formed. The U.S. suddenly found itself among odd bedfellows on a list of most executions in 1999:

1. China, 2. Iraq, 3. Congo, 4. U.SA., 5. Iran.

The “pro” argument says that it’s churlish for Europeans, like myself, to get snotty about this. After all, the homicide rate in the U.S. is ten times higher than it is in Western Europe, so maybe stiffer sentences are in order– and so the debate becomes more turbid. However, it is clear that America’s apparent insensate and obdurate position on the death penalty has considerably degraded the image of the U.S. in democratic Europe, perhaps negating its moral leadership in the world. An editorial in France’s Le Monde accurately summed up European feeling: “ The death penalty, along with limits on abortion rights and the sale of firearms, is digging a gulf between America and the Old Continent, a gulf of values and misunderstanding that drives them apart. In this domain, President Bush, more than any of his predecessors, incarnates an America that is more and more distant from Europe.” Amongst considerable opprobrium, Bush is often described by left-wing politicians as a “serial assassin” (authorizing as he did 154 executions during his tenure as Governor of Texas).

International criticism, of course, goes unheeded in the traditionally inward-looking United States. Scalia even postulated that, “Secular Europe’s thought on this matter is the legacy of Napoleon, Hegel and Freud.” Europeans would argue that Adolph Hitler and Joseph Stalin probably had a greater influence on their present thinking.

The oft-held view in Europe is that the U.S.’s barbaric avidity for execution is just a reflection of a brutal society. But claiming the moral high ground isn’t that simple. Okay, the U.S. is in violation of the U.N. Resolution on Human Rights, and there are more firearms in private hands in the U.S. than in the entire Chinese Army, but in truth, popular opinion in Europe doesn’t always accurately reflect the views of its politicians and representatives.

The oft-held view in Europe is that the U.S.’s barbaric avidity for execution is just a reflection of a brutal society. But claiming the moral high ground isn’t that simple. Okay, the U.S. is in violation of the U.N. Resolution on Human Rights, and there are more firearms in private hands in the U.S. than in the entire Chinese Army, but in truth, popular opinion in Europe doesn’t always accurately reflect the views of its politicians and representatives.

When polled, people’s opinions are remarkably similar to those held in the U.S. For instance, in the U.K., support for the return of capital punishment grew to 70% in the late 1990’s in the wake of highly publicized murders of children. (It currently stands at 60%.) In the Netherlands, the most liberal of societies, the figure is 52% in favor. In France and Italy, support sits at 50%. The new Eastern European members of the EU have all abolished capital punishment as a prerequisite of membership, even though 60% of people favor its retention. Boris Yeltsin commuted 700 prisoners on Russia’s Death Rows to “life imprisonment” in order to gain membership to the Council of Europe.

It is argued that it’s not so much a divide in U.S. and European public opinion as a difference between political cultures. The difference in Europe is that governments decided to abolish capital punishment for intellectual and moral reasons, despite the will of the populace. This couldn’t happen in the U.S. It can’t just be explained away as the Faustian bargain that American politicians strike – votes being more important than principles. As reasoned in Stuart Banner’s excellent book, The Death Penalty: An American History, it could be argued that the United States is more, well, democratic. After all, no U.S. politician would run for office on an issue if the polls said that the electorate was against it. Increasingly, this very issue actually defines a candidate to the voters. And so the effect on government, and the law, becomes most directly the will of the people. Hence, the moral high ground is not easily yielded.

Whatever side of the debate we all sit on – whether you see it as an abasement of all civilized human values or as a necessary evil in an increasingly evil society – it’s obvious that it’s not a clear-cut issue and that if it isn’t 100% clear, we have no right to so readily take the lives of other human beings.

Once again, Justice Blackmun’s words of 25 years ago: “The death penalty remains fraught with arbitrariness, discrimination, caprice and mistake.” Nothing has changed. Too many of those that are sent to their death, have been black, Hispanic, uneducated and poor. The execution of juveniles and the mentally ill and retarded cannot be acceptable in a civilized society. A patently flawed and fallible justice system continues to send innocents to their death. Even Justice Scalia agrees with this: “Death is no big deal,” he said. “But the execution of an innocent is.”

The overwhelming evidence shows that the threat of Death Row, and ultimately many years later the threat of injection of lethal poison, certainly does not deter violent crime. But the fear of crime – all crime – affects everyone’s lives and this real concern causes people to continue to demand the greatest retribution.

My own views are probably close to those expressed in Constance’s speech outside the Texas State Capitol in our film.

Sc. 143. AUSTIN CAPITOL – DAY

CONSTANCE

When you kill someone, you rob their family. Not just of a loved one, but of their humanity — you harden their hearts with hate, you take away their capacity for civilized dispassion, you condemn them to blood lust. It’s a cruel, horrible thing. But indulging that hate will never help. The damage is done, and once we’ve had our pound of flesh we’re still hungry – we leave the Death House muttering that lethal injection was just too good for them. In the end, a civilized society must live with a hard truth: he who seeks revenge digs two graves.

Afterwards

The death penalty debate continues in the United States.

There were 37 excecutions in the US in 2008, the lowest number since 1994.

In 2011, there were 43 excecutions across 13 states.

In 2011, the US was the only G8 country in the Western Hemisphere still practising Capital Punishment.