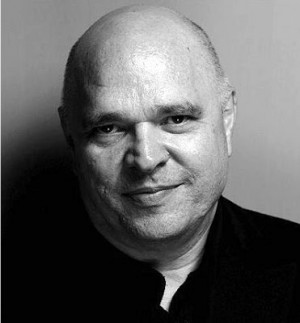

ANTHONY MINGHELLA: AN APPRECIATION

BY SIR ALAN PARKER

The Sunday Times, March, 2008 Last week my friend Anthony Minghella died. His death was sudden, unexpected, shocking and met with utter dismay by all who knew him — and many that didn’t. In my lifetime in the film industry I can’t remember such collected outpourings of sorrow, sadness and such sense of colossal loss. This was a man of 54 whose work had been among us for scarcely twenty years and which promised us so many riches in the twenty years that should have followed.

Last week my friend Anthony Minghella died. His death was sudden, unexpected, shocking and met with utter dismay by all who knew him — and many that didn’t. In my lifetime in the film industry I can’t remember such collected outpourings of sorrow, sadness and such sense of colossal loss. This was a man of 54 whose work had been among us for scarcely twenty years and which promised us so many riches in the twenty years that should have followed.

The director Hugh Hudson had first phoned me with the news. I squeezed my eyes together and shouted “No!” Apart from my close family, I can’t imagine reacting that way to someone’s death. Suddenly the phone began to ring off the hook from colleagues and the press. The customary requests for comments and interviews were bewildering and I stumbled to say something relevant and adequate to justify Anthony’s life and impact on the world of film. “He was a brilliant director and beautiful man” is what I kept stammering. Others added to the elegiacal deluge perhaps more eloquently, but the reaction was universally the same. This was a man whose abilities, as a consummate filmmaker — as writer, director, and producer — were always intermingled with his qualities as a man. Anthony was always eloquent with a graceful, way with words, not only in his writing, but also by making the most casual of conversations seem important. On many occasions I’ve witnessed him making impromptu speeches that sounded like someone reading verses from Keats. His Oscar acceptance speech had us all scurrying for the dictionary for the meaning of the word ‘uxorious’. He was also kind, gentle, thoughtful, generous and humble. Now, trite as these words might appear, I have to remind myself that I’m talking about someone in the film industry— a world where such attributes are far from plentiful.

Why did one man affect all of us who knew him so much? After all, Anthony’s six films are a desperately brief legacy and not all were received by film critics with the good grace with which they were made. His nascent career as an opera director has left us only with his sublime production of ‘Madame Butterfly’ created at the ENO and, uniquely for an operatic parvenu, it was rapturously received at the Met in New York. The direction of his career appeared to be dominated by film and so his career as a playwright would appear to be curtailed, if not abandoned. Also he was a great crusader and activist for the culture of film as chairman of the British Film Institute, a job from which he very recently stepped down after five years, feeling that he should concentrate on his ‘day job’.

Stewart Till, John Woodward and I were due to have dinner with Anthony this week, to thank Anthony for his five years at the BFI and his five years on the Film Council board, but it was cancelled because he had “ double booked”. Little did we know that he would be checking in to the Charing Cross Hospital for an operation for a lump on his neck due to cancer of the throat and tonsils. He had cancelled a screening of his latest film at the Botswana Embassy due to laryngitis, which many who knew him found odd. The operation for the growth on his neck was deemed to have gone well and everyone was optimistic, but he suffered a subsequent haemorrhage, which resulted in his death at 5 a.m. Tuesday morning.

As chairman of the UK Film Council it had been my job to persuade Anthony to take over at the British Film Institute. The BFI, at the time, was at a very low point and in desperate need of reorganisation and new leadership. The problem was that Anthony was in Romania in the middle of shooting ‘Cold Mountain’. I dutifully took a plane to Bucharest and was driven deep into the Carpathian mountains for my rendez-vous with the “Hollywood people” hidden in the snow. As the car climbed upwards, the scenery was breathtaking and as I passed the hay carts and gypsy encampments of this untouched almost medieval place, I could see why he had chosen this location for his film.

Anthony had first been given Charles Frazer’s novel of ‘Cold Mountain’ by Michael Ondaatje and on reading the proof copy Anthony described it in his inimitable fashion: “The prose is like denim, made for work: serious, steadfast sentences which talk of the land, of loss, of a terrible damage to the country, the end of something…the flakes of snow fall in the pages with tragic consequences.” Choosing Romania as a location would eventually rebound at Anthony by the American film unions who were mortified that such a quintessential story of the American Civil War should be made as a ‘runaway production’ and not even at Pinewood, but in a country they’d never even heard of. In truth, it was made in Romania partly because it was cheaper and partly for creative reasons. The enormous, staggeringly shot battle scenes that open the film would not have been economically possible in the States, and creatively, the untouched, pristine, pine-clad mountain valley of Polana Brasov was a wonderful natural film set in which to build the Cold Mountain town and farms, allowing an uninterrupted 360º shooting vista without a Burger King in sight.

My Romanian driver dropped me at the set where they were filming. It’s fair to say that no director is comfortable on another’s set. Fortunately, I knew many of the crew and so I tiptoed to hide behind them as Jude Law, on repeated takes, ran out of a log cabin. It was clear that Anthony didn’t work like me. You would have been hard pressed to know that he was even there. He subtly and charmingly worked with the actors, cinematographer and stalwart script supervisor, without ever raising his voice as he softly guided them, convinced them more than directed them, to the vision of the scene he had in his head. He stroked their faces, cuddled them, hushed their protests with a finger to the lips and kissed them on cheeks barely visible beneath woollen balaclavas.

That evening I had dinner with Anthony at his rented Romanian farmhouse in the skiing village of Zarnesti where the crew were staying. He was watching his weight, which often yo-yo-ed up and down, and there was an enormous exercise bike in the hallway. For dinner we were served carp in brine and pickled cabbage. Gracious as ever, Anthony effusively complimented the housekeeper when she cleared the plates, even though we had both struggled to eat a thing. He said, “The food’s crap, but she’s a lovely lady and very good for my diet.” He thought that the job of Chairman of the British Film Institute was a poisoned chalice. After all, most people would avoid the job, attacked as it traditionally was by the film press, the employees of the BFI, the film community and the anoraks who habitually attend the National Film Theatre. He chewed his carp, spat out a bone and said, “Alan, I’ll do it.” And do it he did. To start with, he reorganised and refocused the organization by appointing a new CEO, Amanda Nevil, and revitalising the board. He helped to put the BFI on a more realistic economic footing and paved the way for the precious film archives out at Berkhamsted to be protected, digitalised and made more accessible. What’s astonishing is that he did all this whilst pursuing his very busy career and just swatted away his BFI detractors by being honest, frank, realistic and giving them a cuddle. The anoraks were lost for words.

But what of that busy career? As you look back on Anthony’s work you have to be shocked by his sudden death, but also blessed by his life. ‘Blessed’ is an overused word, but one he used often. In the pursuit of Anthony’s particular ‘Rosebud’, you have to look at not so much at what he achieved, but how he did it. This was a man who was so much more than a sum of his parts.

If you were writing a scene one, what better material than being brought up in an ice cream parlour on the Isle of Wight? Ice cream made in the back shed by Italian/Scottish immigrants. This would not, by many, be seen as an underprivileged beginning. Ice cream vendors? Of Italian origin? When did a British filmmaker ever have such a romantic start?

He maintained that there was never a book in his house and that he relied on the local library. But he also said, “ I have never resented my childhood. It was a blessed childhood in the sense that I had a wonderful family. I don’t resent the lack of cultural information I had as a child. It made me enquiring and curious. I’ve always imagined that you find your culture rather than receiving it on a plate.” At the Minghella Ice Cream Parlour on the Isle of Wight, after each of Anthony’s films, his mother would name a new ice cream after his latest opus. ‘Cold Mountain’ was easy, but ‘First Ladies No 1 Detective Agency’ will be bit of a mouthful.

He went to Hull University where he eventually abandoned his doctoral thesis on his beloved Beckett and after a stint teaching began writing plays and paying his dues by working in television as a writer. He was always busy and this set a pattern for his future life. He wrote and script-edited for ‘Grange Hill’, wrote episodes of East Enders, Inspector Morse and a whole series for the Henson Muppet Factory. And along the way he won the London Theatre Critics award for best play for ‘Made in Bangkok.’

‘Truly Madly Deeply’ was Anthony’s big break. Mark Shivas, the doyen of British TV producers, was ensconced as head of drama at the BBC and had previously made the three part Channel 4 series, ‘What If It’s Raining’ which had been much acclaimed and written by Anthony. Shivas commissioned ‘Truly Madly Deeply’, which was originally called ‘Cello’. It was never meant to be a feature film, shot as it was on 16mm with the usual restrictive BBC union arrangements. When finished, Anthony’s representatives in Los Angeles had the film viewed and it was bought by Samuel Goldwyn Jnr’s company and the negative enlarged for theatrical release. Sam Jnr said — with a line worthy of Sam Snr — “ No film should be named after a musical instrument.” The title was subsequently changed. Ironically, the biggest art house movie that year was ‘The Piano”.

And then comes the big question in our Citizen Kane story. Why would anyone in Los Angeles or San Francisco, particularly a, renegade, hard-nosed producer called Saul Zaentz, entrust a multi-million dollar budgeted film, ‘The English Patient’ to a cherubic English writer/director who had made an unsuccessful British film that was buried at the box-office and received reserved, critical acclaim? Anthony had followed ‘Truly, madly’ with the unmemorable ‘Mr Wonderful’. If Anthony was blessed it was first as a writer. He thought of himself as a writer who was lucky enough to direct some of his scripts. Anthony had his fingerprints on so many films and screenplays for which he wasn’t credited. He could analyse and reconstruct a script in a single conversation. And as Mark Shivas said,” “He could charm the birds off the trees.” Together with his business partner, the veteran Hollywood director Sydney Pollack, Anthony went on to have his name as a producer on many films including ‘Michael Clayton’, ‘The Interpreter’, ‘The Quiet American’ and the upcoming Stephen Daldry film of ‘The Reader’. Pollack said, “Anthony was a realistic romanticist…to most observers, a sunny soul who exuded a gentleness that should never be mistaken for a lack of tenacity and resolve.”

It was the great Saul Zaentz who introduced Anthony to a way of making films that Anthony embraced for the next part of his career: a completely international crew, cherry picked from the United States, Italy Australia and Britain.

One obituary said that he was Orson Welles, Harold Pinter, David Lean and Richard Attenborough all rolled into one. Certainly he had a Wellesian presence with his bald football of a head atop a portly figure, often draped in Johnny Cash black. He made at least one film worthy of Lean and had a wheelbarrow full of Oscars to show for it. The acerbic theatricality of Pinter? Perhaps. Attenborough? Well, he certainly shared Dickie’s angel tongue and commitment to fighting for the film industry. And whenever I saw Anthony he would give me a ‘lovey’ hug and a kiss on the cheek. He was a man loved by other men.

He even tried his hand at a party political broadcast — filming Blair and Brown on the end of a long lens like two lovers on a study date — further proof that Anthony saw good in everyone. He tirelessly lobbied for a new cinema centre on the South Bank. It was Anthony’s passion to tear down the old NFT and to have a home for film that rivalled the one for the visual arts at the Tate Modern.

On Easter Sunday BBC 1 showed Anthony’s latest work, ‘The No 1, Ladies Detective Agency’, which he co-wrote with Richard Curtis. It was a gruelling shoot made entirely in Botswana and was Anthony’s attempt to show a joyous, different Africa to the violence and sickness of much of the continent.

It is incomprehensible to imagine the pain and loss his wife Carolyn, daughter Hannah and son Max must be feeling. The entire film industry, on both sides of the Atlantic, grieves with them.