Advertising And Commercials

Originally published by CamerimageWhen I left school I went into advertising working for a small agency in Fleet Street called Maxwell Clarke. I started briefly in the mailroom and, after a number of mundane production jobs with titles like ‘copy forwarding’ and ‘block chasing’, I began writing ads in the evening — showing them the next day to the creative department guys who generously took me under their wing, marking my work like schoolteachers: “Scotch whisky ad, 6 out of 10, must try harder. No one would buy this shit.” These ads were mostly written late at night, on my parents’ kitchen table, in our small flat in Islington. One night my Dad, unimpressed by my burning of the midnight oil, stormed in to the kitchen, (which was, admittedly, two feet across the small hall from his bedroom) and switched off the lights, saying he couldn’t sleep and, as he paid the electricity bills, this midnight writing bullshit should stop. He was never very encouraging of my creative endeavours. (When I sent him my first novel he asked who had written it.) Consequently, the next day I went into see the agency boss and persuaded him to take me on as a junior copywriter, full time.

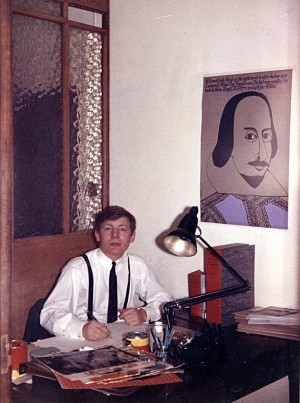

Alan Parker, junior copywriter, Maxwell Clarke, 1964

In my first year I must have written more than 300 ads — most of them were not very good, but I was nothing but industrious. As the hotshot American agencies opened offices in London in the early sixties, I applied for a job at one of them, Papert Koenig Lois (PKL). Armed with a portfolio the size of a medium sized suitcase, I got the job as a copywriter, albeit at the bottom end of the roster. My boss at PKL was Peter Mayle, who went on to write his very successful books on Provence. The problem with the London version of PKL was that it bore little resemblance to the New York agency — famous for it’s seminal ads by the legendary George Lois and Julian Koenig. However, in London, our boss was a New York thug called Joe Sacco, who bullied everyone and made our lives a misery. His party trick was throwing his coffee mug at the wall and, on occasion, blood was shed necessitating trips to the hospital. And so my art director Paul Windsor and I went over to CDP, which at the time was becoming London’s most prestigious agency. Paul had worked there previously and I was very much clinging to his coat tails. After our first interview, we returned to PKL in Sloane Street to find Peter Mayle pacing outside on the pavement. “Don’t go in”, he said. “Joe has found out about your interview and is threatening to kill you. There’s coffee all over the wall.” According to Peter Mayle, Sacco was mad at me leaving and screaming at the top of his lungs, “When that kid came here he couldn’t even open a goddam bottle of wine. He didn’t even have a fucking copy of ‘Fowlers Modern English Usage’. I’ll stuff it up his ass if he comes back here.” Peter is not always reliable about these things, but to be cautious, Paul and I promptly went home and fortunately were offered the jobs at CDP.

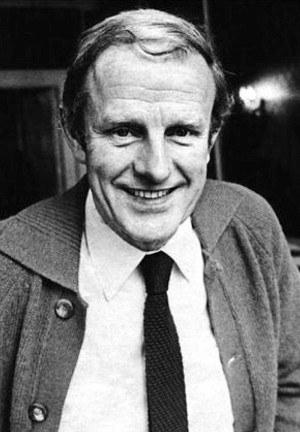

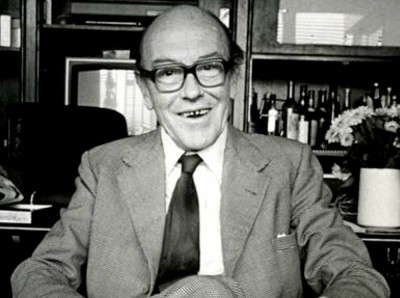

Colin Millward, Creative Director of CDP. A dour, shy, hard to please, Yorkshireman, educated at the Royal College of Art, he had absolute sway over all the creative work produced. As mentor (and tormentor) to myself, Charles Saatchi, David Puttnam, Frank Lowe, and many others who worked for him, he fashioned the entire creative ethos for which CDP became famous. Often unheralded, he was probably the most influential creative executive that the British advertising industry has ever produced.

Collett Dickenson Pearce (CDP) was a wonderful, creative environment, with most of London’s best advertising writers and art directors working away in small nondescript offices, along a narrow corridor, on the fourth floor of an unattractive building near Tottenham Court Road. My friends there, like David Puttnam, who was an account executive, and Charles Saatchi, a copywriter, went on to other illustrious careers, as did many others. This period in British advertising has been referred to as the beginnings of ‘the golden age of advertising’ and CDP was at the forefront, with a reputation as the most anarchic and creative agency, transforming as it did the way advertising looked and sounded — for which we enjoyed great success as we contributed, in some small way, to the 60’s revolution in Britain.

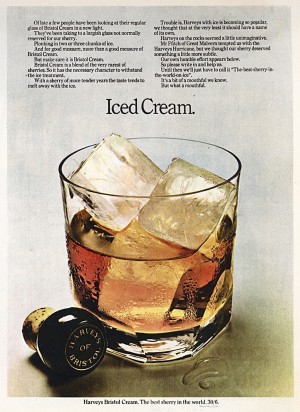

Alan Parker CDP ad for Harvey’s Bristol Cream, one of the first, whole page colour ads in a national newspaper. John Pearce, the boss of CDP, said of the colloquial copy, “We spent years putting Harvey’s Bristol Cream on a pedestal and Parker comes along and sells it off of a barrow.”

Puttnam left CDP to open a business as a photographer’s agent and Charles, along with his art director, Ross Cramer headed up one of the three creative groups at CDP, as did I with my art director, Paul Windsor. Presiding over all of us was the creative director— the much venerated and formidable, Colin Millward.

Colin, a dour, oddly shy, Yorkshireman encouraged this corridor-full of noisy, eccentric misfits — most of us in our early twenties, to be as courageous as possible with their work and, if he gave it his approval, it would be sent down to the third floor for the account men to sell. If the client didn’t approve the work then John Pearce promptly fired the client. It was a simple system and one which helped the agency grow considerably.

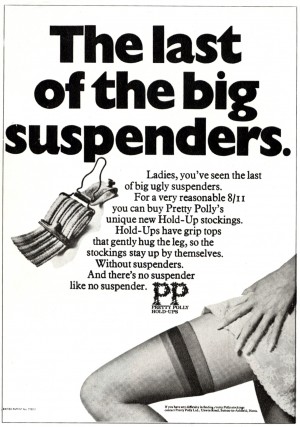

Pretty Polly stockings CDP ad: Copywriter Alan Parker, Art Director Paul Windsor.

We were all exceptionally well paid, thanks to Charles Saatchi — or Charlie as he was called then — who was smarter and more worldly than the rest of us oiks on CDP’s fourth floor — he was always the first to get a salary hike and, curiously, he even started to buy paintings, which we all thought was completely daft. Ross Cramer sarcastically said that Charles was in to minimalism. He had just bought a painting that was a plain, white canvas with a small red dot stuck on in the bottom right hand corner.

One day Charles and David Puttnam invited me to lunch at a Greek restaurant in Charlotte Street, rather unimaginatively called the Kebab & Humus. Halfway through lunch, Charles and David leaned forward conspiratorially and said, “Alan, we’re going into the film business and today we’re going to discover you.” Why they were discovering me, and not me them, ran through my mind. The plan was for me to write a script, as would Charles and also the illustrator Alan Aldrich. Puttnam would then attempt to sell them. My first effort was a treatment called ‘Sophie Breams’ based on the Beatles’ song, ‘Eleanor Rigby’. Charles and David were more polite about the treatment than the work probably deserved. Puttnam then called me to say that he had secured the rights to seven Bee Gees songs, around which we could shape a film. At the time, the pre-falsetto Bee Gees were popular, but had not yet achieved the greater success that came with Saturday Night Fever. I wrote a screenplay— late at night in longhand —inspired by a lyric of the Bee Gees song ’The First of May’:

When I was small and Christmas trees were tall

We used to love while others used to play

The story was an amalgam of my own childhood memories mixed with some of Puttnam’s. The title, ‘Melody’ came from another Bee Gees song, ‘Melody Fair’.

David went off to New York and had a torrid time in the nasty world of film finance, but with great tenacity he eventually raised the money from an odd source: the Seagram’s billionaire, Edgar Bronfman. Apparently his son, Edgar Jnr read the script and urged his father to make the film. Edgar Jnr was a ‘runner’ on the film, which was directed by Waris Hussein. Waris was a very sensitive director, one of many Cambridge educated writers and directors who cut their teeth on BBC drama. Apparently, Waris got his intro to the BBC because his mother was famous for reading the news in Hindi for the BBC World Service. I was not involved with the actual shooting : for a writer there’s little to do on a film set except get in the way of the electricians. I did however direct a few vignettes for the sports day sequence.

Wes Anderson kindly acknowledged that Melody was one of the influences for his film Moonrise Kingdom.

Charles Saatchi’s script (‘The Carpet Man’) sadly didn’t get made and so he instantly lost interest in the film industry and announced that he was going to start an advertising agency with his brother Maurice. A wise decision as it turned out.

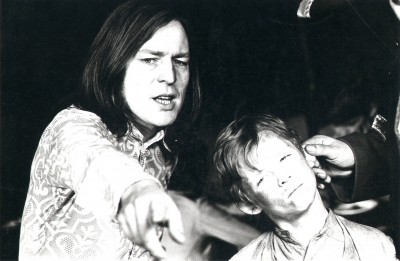

Jack Wild (Ornshaw), Mark Lester (Daniel) in Melody directed by Waris Hussein

Commercials were in their infancy and so I nervously asked Colin Millward if we could have a budget to experiment on 16mm film in the agency basement.

The empty, cavernous space was as big as a car park — in fact it was a car park except that they had forgotten to build a ramp down to it, and so it became our own film studio. Everyone seemed to know how to operate something except me. I had little or no knowledge of the mysteries of the Spectra light meter, the Arriflex camera, the Nagra tape recorder or the Moviola editing machine. Because of my ineptness, it was suggested that, as I had written the scripts, I should be the one who said “Action” and “Cut” – after all, any fool could do that. And this I duly did. I’ve always said that directing is a crash course in megalomania and so I rather took to my new job. From that moment on, I was hooked.

We couldn’t afford professional actors and so we used the agency staff in the pilot commercials. The most helpful were the volunteers from the accounting and media departments (by far and away the best sports—probably because their actual jobs were so dull that they enjoyed being actors for a couple of hours). As our confidence grew, the “basement films” became more and more ambitious. These early efforts culminated in a Benson & Hedges Pipe Tobacco film depicting a pre-1917 Russian ball, accompanied by Jacques Lousier music. The CDP accountant ladies were decked out in their lace and tiaras; the media-planning gentlemen in their long tails and Count Vronsky uniforms, as they waltzed among the candelabra. It was at that moment that John Pearce, CDP’s uber boss, was conducting a tour of the agency’s main floor with a prospective client. The place was deserted with absolutely no one at their desks. Pearce, rarely flummoxed, was taken aback.

“Where the hell is everyone?” he snapped.

John Pearce, “JP”, the patriarch of CDP.

With his wicked, nicotine stained smile and mischievous demeanor, he set the rules for CDP’s anarchic and revolutionary business practice. Giving all power to Millward’s creative department, he was not afraid to fire any client, however large, who didn’t accept our work.

“They’re in the basement with Alan Parker, making a commercial, Mr Pearce,” answered a timid secretary. The next day, I was called in to the agency boardroom for a meeting with the bosses, Colin Millward, Ronnie Dickenson and John Pearce. JP, as he was referred to, was an eccentric, brilliant and imposing figure with a wicked, nicotine stained smile. He chain-smoked Benson & Hedges, a brand whose marketing success he was largely responsible for — and whose sales he greatly contributed to. He was also rarely without a glass of whisky, whatever the time of day. Pearce looked at me across the top of his half-frame spectacles, “Alan, you’re leaving.” I was devastated. I’d never been fired in my life. He continued, “We’ve decided that you should leave and start a commercials production company.” “And we will underwrite a bank loan until you get on your feet” added Dickenson. “And most probably, we’ll give you quite a bit of work to direct.” Concluded Millward, whilst attending to his nails, as he always did.

And so I left CDP.

I started our commercials I company — rather grandly called The Alan Parker Film Company — with the producer, Alan Marshall, who I had worked with at CDP.

I first met Alan when he was an editor in a small commercials company in Berwick Street Market, Soho. He had already gathered quite a fearsome reputation for his no nonsense personality — he had no time for dilettantes or bullshit and many of his assistants allegedly ended up in the piles of rotten market fruit and veg. He also had a reputation for his extraordinary professionalism and so he had been recruited as a producer in CDP’s nascent TV department. At the time, I was a ‘creative group head’ and would be regaled daily with stories of Alan’s rudeness and brilliance, as he unpretentiously demystified the intricacies of the filmmaking process for the ignorant copywriters and art directors. The moving image and TV commercials were new to CDP — known for its press ads — but suddenly CDP began to clean up in the TV commercials awards and the common denominator was always Alan Marshall. A gruff North Londoner, he had a sparse, colourful vocabulary, but a highly sophisticated, innate understanding of film, from which everyone benefitted, not least of all myself. When it came to starting a commercials company, he was an obvious partner and the two of us left CDP together to set up shop in a single-room office in Soho.

Directing Birdseye ‘Oliver Twist’ commercial for CDP

I was still quite green as a director and prior to every shoot, Alan would walk me through the set the night before, discussing the shots and the possible ways they could cut together. We were fortunate to get the very best scripts from CDP and so we were immediately off and running and in our first year were lucky enough to win quite a few awards.

Joan Collins and Leonard Rossiter, Cinzano, for CDP

As our company became more successful we were shooting a new commercial every week, sometimes two a week. It became a wonderful film school for me as I learned my craft, shot by shot, lens by lens, week in and week out. When John Pearce retired at CDP, Frank Lowe took over and proved to be even more eccentric and inspired than JP — well, inspired enough to give us rather a lot of work. Between Ridley Scott’s company and ourselves we scooped up most of the good scripts. Ridley and I were very competitive, although we did very different work. If a script opened with, “We see a beautiful girl running in slow motion along a golden Caribbean beach.” Ridley would get that. If a script read, “We see two overweight ladies talking at a lunch counter in Shepherd’s Bush.” I would get that.

All text © Alan Parker